![[ADRN Working Paper] Democratic Backsliding in South Korea](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/20250702151055558995988.jpg)

[ADRN Working Paper] Democratic Backsliding in South Korea

| | 2025-07-02

Asia Democracy Research Network

The Asia Democracy Research Network (ADRN) conducted research on recent democratic backsliding in South Korea, recognizing the importance of investigating implications of this political turmoil and providing suggestions to prevent further deterioration. The researchers point out that the underlying causes of the backsliding lie in the presidential systеm, which gives the president an unofficial degree of authority, and in the political parties’ violation of the norm of mutual forbearance. They suggest that current crisis is closer to a “top-down erosion,” which resulted from political elites disregarding democratic principles, despite stable public support for democracy.

South Korea, one of the leading democracies in Asia, has undergone democratic backsliding sparked by the declaration of martial law by President. As the President was impeached and the new government has established in accordance with constitutional procedure, this episode demonstrated South Korea’s democratic resilience. Nevertheless, it is still necessary to investigate backgrounds and implications of this political turmoil, thereby providing suggestions to avoid further deterioration of democracy in South Korea and other Asian countries.

With the critical awareness that effective solutions addressing democratic backsliding require a proper assessment of this phenomenon, ADRN conducted this research project, extending the scope from institutional reforms to behavior of political elites and citizens’ perceptions.

The report investigates contemporary questions such as:

● Does South Korean presidential systеm allow president overwhelming power?

● What is the negative synergy effect of hardline tactics by the president and legislature?

● Does political elites exacerbated conflicts, thereby provoking top-down democratic crisis?

● How has citizens’ confidence in democracy changed during political upheaval?

Drawing on a rich array of resources and data, this report offers country-specific analyses and suggests policy recommendations to enhance democratic resilience in South Korea and the larger Asia region.

Global Spread of Democratic Backsliding and South Korea

Sook Jong Lee

Senior Fellow, East Asia Institute; Distinguished Professor, Sungkyunkwan University

I. Global Spread of Democratic Backsliding

Since the late 2000s, the world has entered an era of democratic backsliding. Two global reports on democracy have drawn the attention of scholars and the media for their classification of regime types. The first report is the annual publication released every March by the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden. The 2025 report, which examined 179 countries, assessed that the quality of democracy experienced by individuals worldwide has regressed to the level of 1985, while the democratic status of individual countries has reverted to that of 1996 (V-Dem Institute 2025). Researchers at the V-Dem Institute describe the past 25 years as the “Third Wave of Autocratization.” Backsliding has been particularly evident in the areas of freedom of expression, freedom of association, clean elections, and the rule of law. It has been especially pronounced in Eastern Europe, South Asia, and Central Asia. Consequently, the number of democratic countries (88) fell below that of authoritarian regimes (91) for the first time in 2024—72% of the global population lives under authoritarian rule. Among democratic countries, only 29 are classified as liberal democracies, making this the smallest group among the four regime types: liberal democracy, electoral democracy, electoral autocracy, and closed autocracy.

The second report is the Democracy Index, published also every March by The Economist in the United Kingdom. Its 2025 report indicated a continuous decline in the average global democracy index since 2010, with backsliding particularly marked in civil liberties, the electoral process and pluralism, and the rule of law (Economist EIU 2025). Owing to this trend, only 25 countries—accounting for 15% of the 167 studied countries and territories—are classified as “full democracies,” representing 6.6% of the studied population. A total of 46 countries, accounting for 27.5% of the studied countries, were “flawed democracies,” representing 38.4% of the population. Regardless of whether flawed or not, these two categories together comprise 43% of the studied countries and 45% of their population. Meanwhile, 60 countries were categorized as “authoritarian regimes,” accounting for 35.9% of the countries studied and 39.2% of the population. The remaining 36 countries were classified as “hybrid regimes,” representing 20.6% of the countries and 15.7% of the studied population.

This global decline in democratic countries has revitalized academic interest in democratic backsliding. Some researchers have focused on the gradual nature of this process, which contrasts with the past abrupt collapses of democracy through military coups. Such gradual backsliding typically erodes democratic systеms slowly through legal frameworks and electoral mechanisms. A few key studies exemplify this transition. Bermeo (2016: 10) identifies three forms of democratic backsliding. The first is the “promissory coup,” in which elected governments are overthrown under the pretense of protecting the democratic order. The actors behind these promissory coups pledge to restore democracy through future elections. Notable examples include the military coups in Thailand and Myanmar. In Myanmar, the military staged a coup and declared a state of emergency on February 1, 2021, promising elections set to take place. But the military government has not kept its promise so far.

The second type is “executive aggrandizement,” wherein an elected government incrementally dismantles institutional checks on its power without changing the regime type, weakening opposition forces. Typically, these governments seize control of legislative or judicial bodies and use them to suppress the opposition. Most democratic backsliding in electoral democracies, such as in Turkey and Hungary, falls into this category. The third type involves the strategic “manipulation of elections,” which employs subtle tactics rather than outright rigging. These include denying candidates equal opportunities, limiting access to media, allocating public funds solely to the ruling party’s campaign, obstructing voter registration, or embedding loyalists in national electoral commissions. These tactics are often deployed in combination.

Scholars affiliated with the V-Dem Institute are publishing research focused on democratic backsliding and the restoration process. Lührmann, a leading scholar in this field, outlines the stages of autocratization. The first stage involves structural and contextual challenges that increase the risk of autocratization. At this point, citizens’ discontent grows due to economic crises, inequality, immigration tensions, political polarization, and the influence of social media. In the absence of democratic parties or processes, and when citizens’ commitment to democratic norms deteriorates, the second stage—anti-pluralism—emerges. If anti-pluralist parties and leaders successfully mobilize voters and win elections, this marks the “onset of autocratization.” Lührmann argues that backsliding can be reversed if checks and balances remain in operation and opposition—whether from citizens, civic groups, or political parties—against autocratization. Without such resilience, the final stage of democratic breakdown begins (Lührmann 2021).

Resilience—efforts that counteract backsliding—can be categorized into “onset resilience,” which prevents autocratization, and “breakdown resilience,” which prevents the collapse of democracy once autocratization has begun. Boese et al. (2021) analyzed 4,372 episodes in 64 democratic countries between 1900 and 2019 and found that the vast majority (98%) did not end in autocratization. However, they also found that once autocratization begins, the probability of democratic survival sharply declines, with only 23% avoiding the collapse of democracy. Notably, 60% of the 64 episodes occurred after 1993, following the Cold War. This study statistically analyzed the factors contributing to democratic resilience and found that judicial checks is key in preventing backsliding—validating the notion that the judiciary is “the last bastion of defense.” Economic development helps prevent the onset of backsliding. Nevertheless, economic development made little difference once backsliding had already begun. Furthermore, the study found that geographic surroundings of having other democratic countries as neighbors and a long history of democratization serve as protective factors against backsliding and collapse (Boese et al. 2021).

The case of South Korea offers a particularly valuable reference point for global research on democratic backsliding and resilience. The relationship between backsliding and resilience is inherently oppositional. South Korea will be a significant case for understanding how direction changes and how one trajectory gains momentum over the other.

II. Democratic Backsliding in South Korea

At the end of last year, democratic backsliding, a topic of global concern, occurred in South Korea. As one of Asia’s leading democracies, the declaration of martial law on December 3 by South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol shocked the international community. Korean National Assembly nullified the martial law within a few hours and passed the bill impeaching President Yoon on December 14. Until the Constitutional Court judges upheld the bill unanimously on April 4, the country had experienced months of serious conflicts driven by intensified political polarization. A new government led by President Lee Jae Myung started right after June 3 snap presidential election. This half year grand episode showed South Korea’s democratic resilience by returning to democratic order through constitutional processes and the rule of law. Nevertheless, the whole process inflicted significant damage on its democratic systеm. This included mass protests from a deeply divided public, legal disputes, and the first instance of mob violence to the court house in the nation’s history. The reports referenced earlier did not overlook this development. The V-Dem Institute reclassified South Korea—previously consistently ranked as a liberal democracy since the early 1990s—as an electoral democracy (41st worldwide). The Economist also downgraded South Korea from a full democracy to a flawed democracy (32nd globally, 5th in Asia).

Multiple factors likely contributed to democratic backsliding in South Korea. At the institutional level, these include the excessive power of the presidency, legislative paralysis due to inter-party conflict, the judicialization of politics, and the politicization of the judiciary. At the societal level, contributing factors include political polarization, escalating social conflicts, the spread of disinformation, and the rise of extremist minority factions. Nonetheless, certain forces have contributed to resilience and have served as checks on democratic decline. Active civic engagement has consistently been a source of resilience during political crises, and adherence to constitutional order has functioned as a constraint on democratic erosion. This deterrence would not have emerged without the national pride Koreans place in their democratization achievements. Nevertheless, the imposition of martial law and the ensuing efforts to restore order served as a wake-up call to scholars of Korean democracy.

The research series “Democratic Backsliding in South Korea” is an academic response to these concerns. This study was initiated with the critical awareness that effective solutions require a proper assessment of democratic backsliding in South Korea. Most discussions have focused on institutional reforms, such as altering the power structure or addressing political polarization by modifying electoral laws. However, it remains uncertain whether institutional reforms alone can alter the behavior of political parties or politicians or improve political culture. With such a critical lens, four scholars analyzed institutional structures and political behavior together.

In the first paper of the series, Professor Jin Seok Bae analyzes whether the recurring signs of democratic backsliding in South Korea originate from the structural features of its presidential systеm. Professor Bae argues that the declaration of martial law in 2024 by then-president Yoon Suk Yeol and the resulting constitutional crisis were caused by a combination of characteristics of presidential systеm, asymmetrical development between political parties and civil society, and the prevailing political culture in South Korea. From a comparative perspective, South Korean constitution does not give president very strong power officially. However, the Korean president can enjoy informal power beyond legal boundaries. He or she can exert control over the legislative and executive bodies through influencing nomination of the ruling party candidates, budgetary allocation authority, appointments of vast positions in the public sector, and public opinion maneuver. Professor Bae also identifies the influence of the President Office over cabinet ministries, submission of ruling party to President authority, legislative gridlock, the rigidity of the single-term presidency, and conflicting dual legitimacy as contributing factors to democratic backsliding. These dynamics have weakened accountability mechanisms, reduced checks on presidential power, and turned political parties into mere electoral tools, while citizens have become objects of emotional mobilization. This pattern is becoming increasingly entrenched.

The author proposes a dual strategy for institutional reform. First, to reform the vertical power structure without requiring a constitutional amendment, he advocates internal democratization of political parties, increased transparency in the nomination process, and expanded citizen participation. Second, for reforms requiring a constitutional amendment, he suggests redistributing power between the president and the National Assembly, limiting emergency powers, and aligning electoral cycles. He emphasizes that as institutions, structures, and political culture are deeply intertwined, institutional redesign must be pursued alongside tangible behavioral changes and the expansion of democratic culture to eradicate the drivers of backsliding.

In the second paper, Professor Jung Kim contends that the constitutional crisis surrounding the declaration of martial law stemmed from the failure to uphold informal norms derived from constitutional provisions—specifically mutual tolerance and institutional forbearance. Professor Kim explains that President Yoon’s declaration of martial law was prompted by escalating tensions between an opposition-controlled National Assembly, which pursued multiple impeachment motions against senior executive officials, and the president, who repeatedly exercised his authority to request reconsideration of legislative bills. Kim argues that the prolonged use of “constitutional hardball tactics” by both sides led President Yoon to adopt a “constitutional beanball tactic” to break the political deadlock. Kim asserts that this choice was shaped by a politically polarized “national narrative” formed over decades of intense electoral competition between conservative and progressive blocs. Over the past ten years, overlaps between the supporter bases of the two major parties have declined, while affective polarization has intensified, increasing the emotional distance between the supporters of two different parties. Accordingly, electoral strategies have shifted from persuading moderate voters to mobilizing core supporters. This environment has rendered the oppositions and the president’s constitutional strategies viable for electoral gains. These developments have substantially eroded the democratic norm of institutional forbearance. President Yoon’s declaration of martial law effectively lowered the political cost of violating the norm of mutual tolerance. Therefore, Kim concludes that democratic backsliding in South Korea is, for the time being, inevitable.

In the third paper of the series, Professor Sunkyoung Park identifies the nature of South Korea’s democratic crisis as a “top-down democratic crisis.” The crisis is not driven by a change in public perception or behavior but by political elites who have exacerbated political conflicts and lost the capacity to resolve them. To explain elite behavior, Park draws on Juan Linz’s concepts of “loyal democrats” and “semi-loyal democrats.” Several politicians in the People Power Party (PPP) promoted claims of electoral fraud. Moreover, a few PPP politicians defended the rioters who broke into the Seoul Western District Court. In this sense, he ruling PPP at the time included a larger proportion of semi-loyal democrats who are responsible for the country’s democratic backsliding.

Park identifies three causes for the emergence of the “top-down democratic crisis.” The first is a phenomenal cause: the party’s democratic self-correction ability weakened due to the diminished influence of moderate conservatives, triggered by repeated electoral defeats in the Seoul metropolitan area and the rise of regionally-based hardliners within the party. The second cause is a decline of exchanges and dialogues between politicians of different parties. Accordingly, opportunities for mutual understanding and political learning have been decreased. Analysis of legislative research group activities across different parties confirms this decrease. The third cause is a change in the incentive structure. Politicians have become increasingly responsive to the voices of extreme minority groups, driven by pressure from aggressive supporters and certain biased new media, rather than representing the broader citizenry. Park argues that this shift has enabled semi-loyal democrats to strengthen their footholds within political parties.

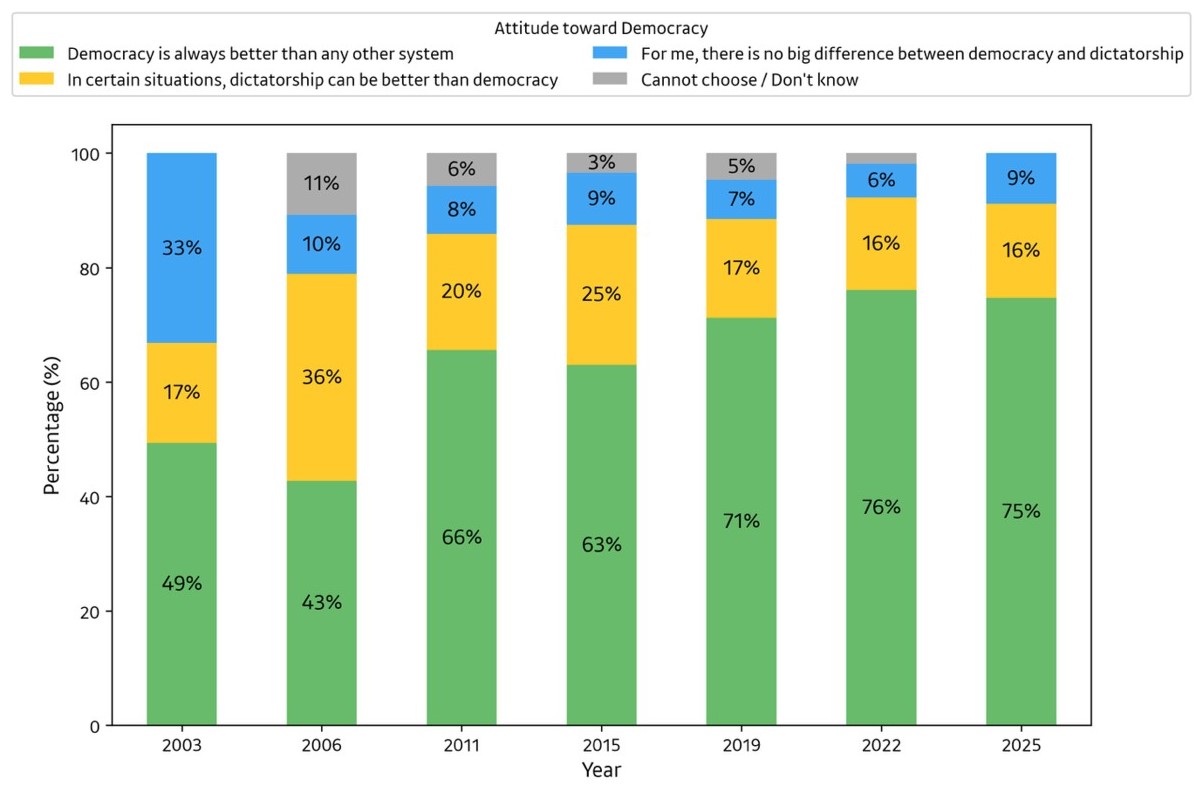

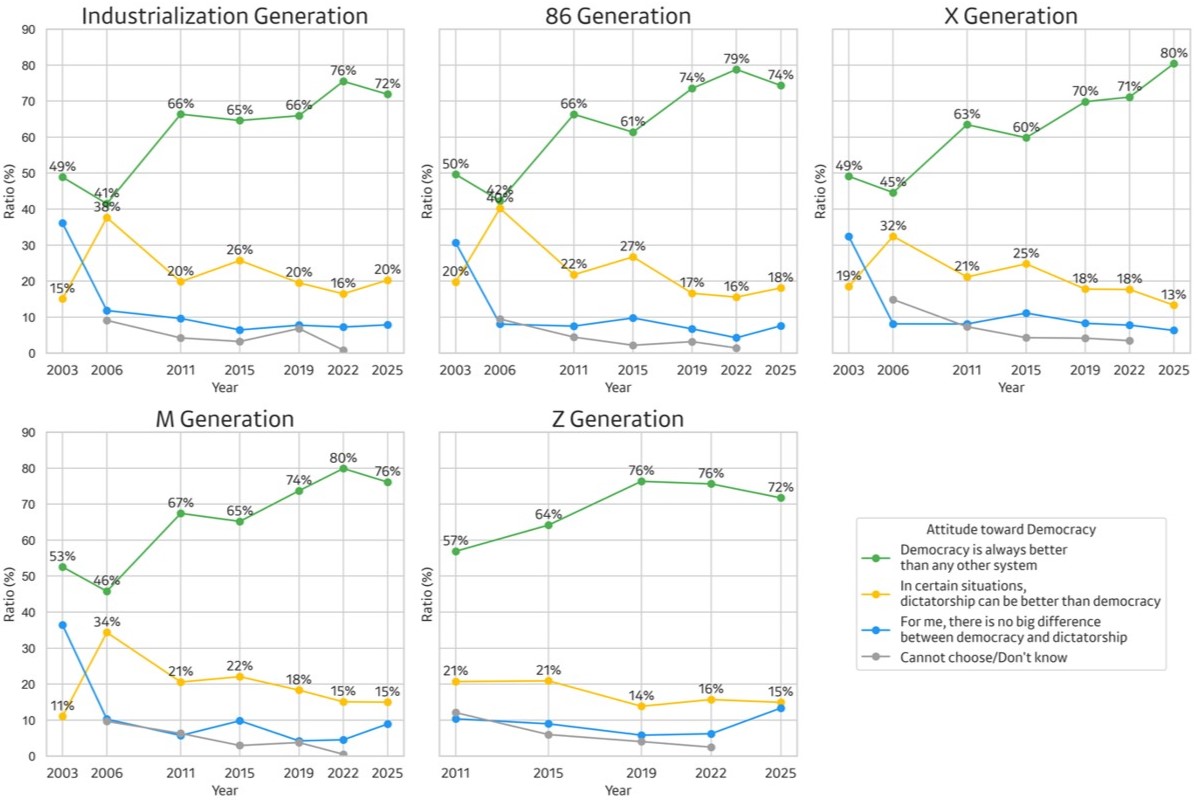

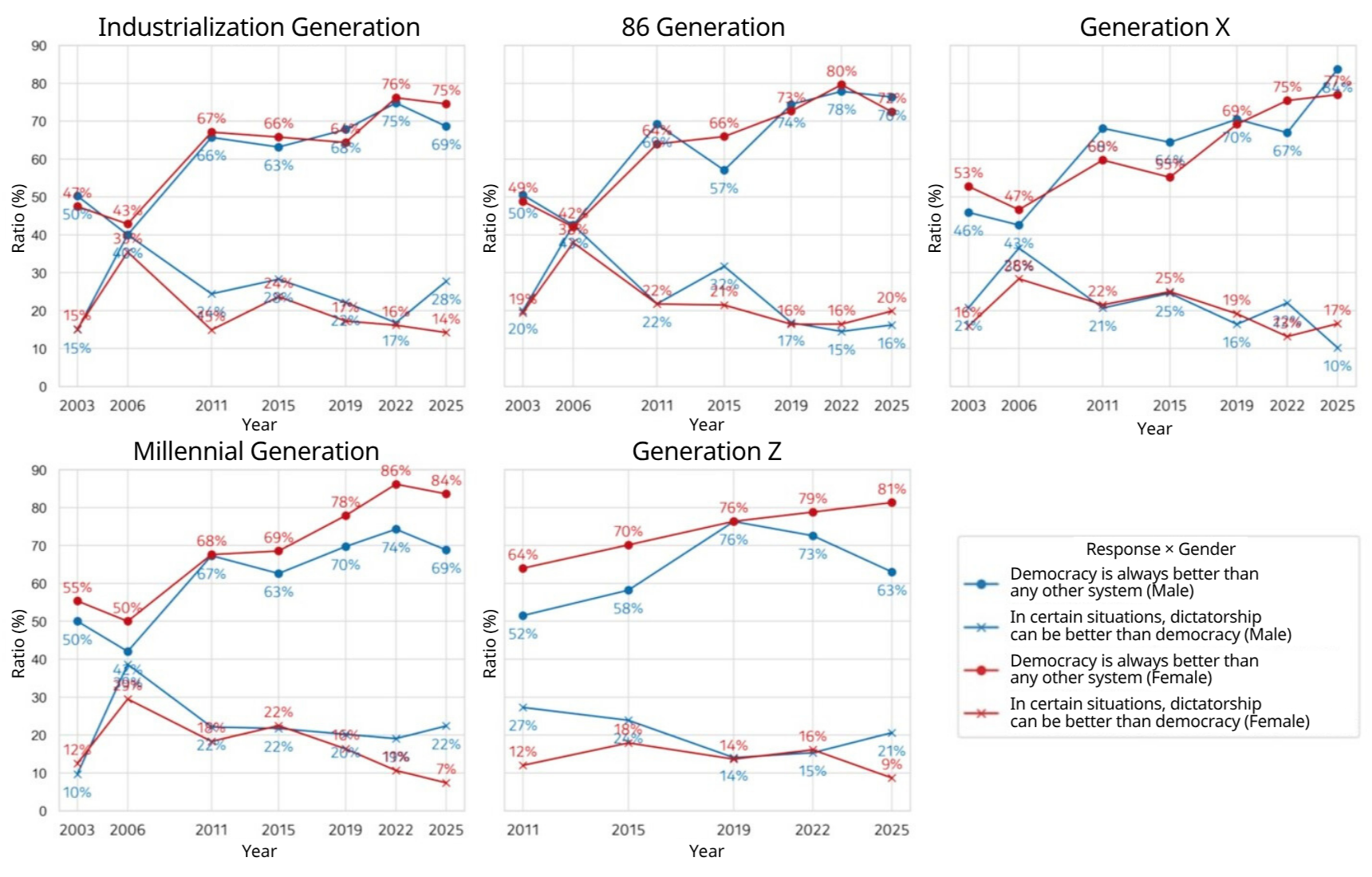

In the fourth paper, Professor Woo Chang Kang asserts that recent democratic backsliding in South Korea is better characterized as “top-down backsliding.” Rather than “bottom-up backsliding.” While the top-down backsliding involves the consolidation or expansion of power by political elites, particularly executive leaders, the bottom-up backsliding occurs when citizens voluntarily withdraw normative support for democracy or reject its values. Kang analyzes data from seven surveys conducted between 2003 and 2025 to assess South Korean citizens’ attitudes toward democracy. He finds that support for democracy in South Korea has steadily increased and remained steadfast despite recent political turmoil. Democracy has essentially become “the only rule of the game” in South Korean society.

However, the 2025 survey revealed a decline in support for democracy and a rise in support for authoritarianism among the males of industrialization generation, millennials, and Gen Z. Conversely, it showed the increased support for democracy among Generation X men, millennial women, and Gen Z women, resulting in minimal change in the overall response ratio. Although support for democracy among millennial and Gen Z males was relatively lower, and a significant decline occurred during the time of post- martial law turmoils, still 60–70% of these groups remained supportive of democracy. Kang argues that this continued South Koreans’ support for democracy will serve as a crucial asset in overcoming any top-down democratic backsliding.

III. Future Directions for Research

This study serves as a foundation for more in-depth investigations into democratic backsliding in South Korea. Two presidents from the conservative party have been impeached within eight years, a reality that undermines the international image of “K-democracy.” The conservative party must undertake painful self-reflection, acknowledging that both presidents were from its ranks, and initiate significant internal reform and reconstruction. The progressive, now ruling, party must also reflect on criticisms that it has engaged in hardball politics by taking advantage of its supermajority in the legislature. Without power-sharing and cooperation with opposition parties, the combination of a dominant ruling party and a strong executive can risk testing the resilience of Korean democracy once again.

Judicial independence is widely regarded by scholars as the final safeguard against democratic backsliding. Therefore, legal and institutional reforms must be carefully examined to ensure the judiciary is free from partisan influence. Public protests, which have historically served as engines of democratic restoration during crises, must now evolve from reactive street mobilization to proactive institutional political engagement to prevent democratic backsliding in advance. As the roles of the ruling and opposition parties inevitably alternate, and public support is inherently fluid, the political arena must transcend short-term partisan interests. Rather, politicians must pursue long-term, bipartisan political reform to make democracy working for citizens.

Furthermore, greater attention must be given to the global trend of democratic backsliding. Comparative studies are academically necessary to identify similarities and differences in democratic backsliding between countries. It is equally important to determine the conditions under which democratic recovery succeeds or fails. Democratic backsliding is contagious, just as democratic resilience can inspire others. When more countries succeed in halting backsliding, the prospect of a global democratic renewal becomes more promising. ■

References

Bermeo, Nancy. 2016. “On Democratic Backsliding.” Journal of Democracy 27, 1: 5-19.

Boese, Vanessa A., Amanda B. Edgell, Sebastian Hellmeier, Seraphine F. Maerz, and Staffan I. Lindberg. 2021. “How democracies prevail: democratic resilience as a two-stage process.” Democratization 28, 5: 885-907.

Economist EIU. 2025. “Democracy Index 2024: What’s wrong with representative democracy?” https://www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/democracy-index-2024/ (Accessed May 14, 2025)

Lührmann, Anna. 2021. “Disrupting the autocratization sequence: towards democratic resilience.” Democratization 28, 1: 22-42.

V-Dem Institute. 2025. Democracy 2025: 25 Years of Autocratization - Democracy Trumped? March 2025. https://www.v-dem.net/documents/61/v-dem-dr__2025_lowres_v2.pdf (Accessed May 14, 2025)

Democratic Backsliding in South Korea:

Institutional Root of Crisis in a Presidential Systеm

Jin Seok Bae

Professor, Gyeongsang National University

I. Introduction: Did the Crisis Stem from the Power Structure?

The declaration of martial law by President Yoon in December 2024 cannot be explained merely as a governance failure by a single adm?nistration or a temporary episode of political instability. This event quickly escalated into a series of constitutional crises, from the impeachment of the president to early presidential elections. It also indicated that the political systеm of South Korea was vulnerable to structural threats that could undermine the foundations of democracy. Subsequently, did South Korea’s democratic crisis stem from the power structure of the presidential systеm, as political leaders and the media unanimously suggested? Or was it the result of President Yoon Suk Yeol’s unique personal traits?

This article does not address this issue as a simple dichotomous choice. Rather, it comprehensively analyzes how the institutional design of the presidential systеm, the organization of political parties, the nature of political culture, and the governing behavior of political actors—who operate within that political culture—interact to paralyze democratic functioning. In particular, the recurring patterns of a “strong president–weak party” structure and confrontational politics rooted in populist affective mobilization have compounded the risks inherent in the presidential systеm, continuously weakening democratic foundations.

This article will examine (i) how structurally concentrated presidential power operates institutionally, (ii) why political parties and the National Assembly fail to function as independent political actors, and (iii) how these institutional operations manifest as democratic backsliding in political practice.

II. Democratic Backsliding or Crisis?

As many researchers point out, democratic backsliding differs from democratic breakdown. Democratic backsliding is not a violent overturn but a systеmic change characterized by the gradual erosion of democracy from within. This process occurs when politicians, who obtain office through democratic elections, undermine democratic values and principles while operating within the formal boundaries of the legal systеm. During this process, executive power expands, harassment of the opposition increases, and suspicions arise regarding state interference in the electoral process (Bermeo 2016).

South Korea has also been discussed within the framework of democratic backsliding. As South Korea experienced the impeachment of President Park Geun-hye and the subsequent adm?nistrations of Moon Jae-in and Yoon Suk Yeol, signs of democratic backsliding were detected. Although the power of the executive body grew, the responsiveness of the executive and the president to legislative oversight by the National Assembly declined. The use of prosecutorial powers to investigate the opposing party further destabilized the political world. Consequently, executive power inevitably influenced the democratic electoral process (Kwon 2023).

Most importantly, the entire backsliding process followed political bloc lines. Emotional polarization has replaced ideological division, and elections have become emotional proxy wars between opposing factions. Citizens were reduced from active political agents to objects of mobilization, rendering participatory democracy virtually paralyzed (Song 2025). Furthermore, the fierce collision between the president and the opposing party over presidential vetoes on legislative bills and impeachment eroded the two unwritten rules of South Korean politics: institutional forbearance and mutual respect. Both sides exercised their legal authority without restraint. As politicians and civilians became entrapped in emotional polarity, the political environment turned confrontational and hostile, leaving no room for compromise or cooperation.

President Yoon’s declaration of martial law elevated South Korea’s democratic crisis, previously discussed under the framework of democratic backsliding, into a new dimension. Historically, discourse on democratic backsliding has emphasized the gradual erosion of democracy, mobilized through legal means. However, the prevailing view is that this incident was an attempted self-coup—more aligned with democratic breakdown. As it involved an effort to overturn democracy through illegal and violent means, it clearly crossed the definitional threshold of democratic backsliding. Ultimately, citizens and the National Assembly thwarted the attempt at martial law. Nevertheless, the episode revealed that even elected leaders in democratic states may contemplate a self-coup to expand their power. Alarmingly, South Korean democracy, once regarded as a model of democratization, came close to not merely democratic backsliding but outright democratic breakdown due to a violent self-coup.

The circumstances confirmed during the impeachment proceedings following the declaration of martial law only deepened South Korea’s democratic crisis. Emotional polarization effortlessly transgresses democratic and constitutional norms. Although the ruling party deliberately incited this sentiment, public aversion to opposition politicians was also evident in survey data, which showed a refusal to accept the impeachment of a president who had clearly violated the Constitution and the law. Some emotionally charged extremist groups even resorted to violence, attempting to seize a courthouse during President Yoon’s investigation and arrest. These extremist groups did not infiltrate the ruling People Power Party; rather, several politicians actively incited them. The emergence of extremist forces—who physically attacked constitutional institutions and are now approaching the center of power through the mainstream conservative party—is a stark warning for South Korean democracy on multiple levels.

III. Institutional Vulnerabilities of the Presidential Systеm and Democratic Backsliding

Is the democratic crisis in South Korea an institutional or structural problem, or does it stem from the flaws of political leaders? Opinions on this question are sharply divided. While some attribute the crisis to the general characteristics of the presidential systеm or the specific nature of the South Korean presidential systеm, others emphasize the lack of governing competence or leadership deficiencies in individual presidents.

First, some prioritize a structural approach. Choi Kwang-Eun (2025) argues that the structural dysfunction inherent in the presidential systеm poses the key threat to democracy. In this view, President Yoon’s attempt at a self-coup cannot be interpreted as merely a personal or exceptional act of a president with unique traits. Instead, critics highlight the excessively concentrated power in the presidency and the weakness of the legislative and judicial branches in checking that power as structural vulnerabilities of the South Korean Constitution. In this context, the political establishment and the media have described the systеm as an “imperial” presidency. The proposed remedy has consistently been the dispersion of presidential power.

Conversely, Yoon Yeojoon and Han Yoonhyung (2025) present a different approach. They argue that responsible and competent leadership can overcome institutional constraints. According to them, the core problem lies in the systеm that allows political leaders lacking in governance philosophy and adm?nistrative competence to become presidents. The solution, they argue, should not be sought in institutional reform but in the selection of qualified leaders. The repeated emergence of “unqualified leaders” has contributed to ongoing democratic instability in South Korea.

Song Ho-Keun (2025) proposes a third, integrative approach. He notes that the reformist overreach of the Roh Moo-hyun adm?nistration, the authoritarian tendencies of the Park Geun-hye adm?nistration, and the attempted declaration of martial law under President Yoon Suk Yeol occurred under the same presidential systеm. He contends that institutional dysfunction and presidential behavior are not separate factors but mutually reinforcing. Similarly, Park Sanghoon (2018) acknowledges that these events may stem from individual presidents’ conduct but argues that the structural conditions enabling repeated patterns of such behavior—presidential office-centered governance and the subordination of political parties—must be addressed through comprehensive reform.

Interpretations of the martial law declaration also differ between actor-based and structural perspectives. These perspectives diverge in identifying the source of the crisis and prescribing reform priorities and strategies for prevention. From the actor’s perspective, President Yoon’s poor governance and ineffective communication skills are identified as the primary causes, with solutions focused on cultivating and selecting political leaders who demonstrate leadership and effective communication skills. Conversely, the structural perspective attributes the crisis to inadequate constitutional provisions on martial law and presidential office-centered governance. In this view, solutions include constitutional amendments focused on decentralizing executive power and enacting legal reforms.

The “imperial presidency” is also debated within this framework. Critics who regard presidential power as excessively concentrated argue that such centralization impedes democratic consolidation. According to this view, the South Korean president possesses excessive constitutional authority compared to presidents in other systеms. However, others argue that the issue lies not in the extent of presidential powers but in the weakness of party politics. They contend that the constitutional powers of the South Korean president are not unusually extensive. Paradoxically, despite the difference in perspectives, South Korean politics often demonstrate a pattern in which the president appears “imperial” at the beginning of the term but “vulnerable” at its end (Bae and Park 2018).

Is the South Korean president’s power exceptionally strong compared to the situation in other countries, justifying the label “imperial”? The index developed by Shugart and Carey (1992) remains one of the most widely used measures of presidential constitutional power. This index classifies presidential power into legislative and non-legislative dimensions and quantifies each item on a four-point scale. According to this index, the South Korean president scores 9 points for legislative powers and 2 points for non-legislative powers, totaling 11 points. Conversely, Brazil and Argentina each scored 19 points, and Chile scored 14 points. The United States scored 12 points, slightly higher than South Korea’s 11 points. Based on this comparison, the constitutional powers of the South Korean president are not sufficiently strong to be characterized as “imperial.” There is little justification for this label from a strictly constitutional perspective.

Nevertheless, the perception of the South Korean presidency as “imperial” persists due to its actual political (de facto) influence, which exceeds its formal constitutional limits. The president exercises wide-ranging informal authority, including control over candidate nominations, leadership in budget formulation, management of key appointments, and influence on public discourse. Especially in relations with the ruling party, the president wields substantial authority surpassing that of a party leader, with the ability to intervene in both the nomination of National Assembly candidates and the overall structure of party primaries. Furthermore, the “Blue House Government,” in which key aspects of governance are handled not by ministers but by “senior presidential secretaries,” also supports the concentration of power in the president, even though it is not stipulated in the Constitution. While constitutionally moderate, South Korea’s presidency enables highly centralized governance in practice, fueling continued criticism of the systеm as “imperial.”

Fundamentally, the problem of the South Korean presidential systеm extends beyond the scope defined by the Constitution and is amplified in practice. Rather than attributing the cause solely to the institution or leadership, the structural vicious cycle generated by their interaction must be recognized. The combination of the president’s legal and extra-legal authority, the institutional inability to check this authority, and the strategies of political actors who exploit this environment places South Korean democracy in a state of recurring crisis.

IV. Relationship Between the President and the Ruling Party

South Korean president has maintained control over the ruling party through constitutional authority and various unofficial means. Even after democratization in 1987 and throughout the “Three-Kims” era, the president continued to exert significant influence over the ruling party and the broader government as its leader. This influence contributed to the perception of an “imperial president.” Although the principle of separation between the party and the government was reinforced during the Roh Moo-hyun adm?nistration, the president’s dominance over the ruling party remains structurally embedded. In South Korea, presidential dominance over the ruling party is primarily exercised through three channels: authority over the nomination of National Assembly candidates, control over appointments, and influence in budget formulation.

First, the authority over candidate nominations is not a formal presidential power. However, in practice, it has become a powerful tool for dominating the ruling party. As regionalism deepened in South Korea after democratization, regional political elites came to regard party nominations as a key mechanism for maintaining their political influence. Consequently, National Assembly candidates prioritized securing party nominations over competing in the general elections. This dynamic created a structure in which the president’s preferences are naturally reflected in the nomination process.

Second, the president’s appointment authority is another critical means of controlling the ruling party. South Korean president holds unilateral authority over numerous appointments, including ministers, vice ministers, and heads of public institutions. The institutional framework permits National Assembly members to serve concurrently as cabinet members. Therefore, the president’s appointment power substantially undermines the fundamental principle of checks and balances between the legislative and executive branches.

Finally, the budget formulation authority serves as a vital channel for the president’s control of the ruling party. Unlike in a pure presidential systеm, the South Korean president exercises significant power in the formulation of the national budget. Thus, the president can influence individual district representatives by allocating funds to their districts. For these representatives, securing a regional budget is directly connected to re-election prospects. Pork barrel spending, also known as “note budgets,” is evidence of the direct influence of the president’s political power. These structural dynamics were apparent when the party and the presidential office were integrated during the Lee Myung-bak adm?nistration and when non-mainstream figures were excluded from nominations under the Park Geun-hye adm?nistration (Hur 2017).

While the institutional framework of the South Korean presidential systеm incorporates the principle of separation between the party and the government, in practice, the president controls the ruling party through nomination, appointment, and budgetary authority. This creates a structural mechanism in which power is concentrated in the individual president.

Such concentration of power distorts the function of elections in South Korean politics, intensifying political tension and hostility. The president’s unilateral control over appointments generates expectations and anxieties that an electoral outcome will result in a wholesale redistribution of state resources and key positions. Consequently, elections have evolved from arenas of compromise and competition into zero-sum contests for political survival. Political parties are increasingly prioritizing the pursuit of power over cooperation. In this context, coalition-building disappears from the political landscape, and political logic shifts toward emotional mobilization and structural hostility.

The recurring pattern of labeling previous adm?nistrations as sources of “deep-rooted evils,” followed by investigations and punitive measures, perpetuates a cycle of political retaliation. This reinforces an adversarial perception wherein opposing political camps are viewed not as competitors but as criminal entities, entrenching a pattern of loyalist and confrontational politics. According to research by the Pew Research Center, South Korea and the United States rank among the lowest in terms of perceived social cohesion between party supporters (Silver 2022). This can be understood as the outcome of institutional power structures and entrenched political polarization.

V. Democratic Backsliding and Recurrent Leadership Crises

All South Korean presidents experience a significant decline in political momentum and approval ratings during the latter half of their terms. This “lame duck” phenomenon is an inevitable product of the institutional framework. Owing to the single-term systеm, presidents struggle to establish a long-term political foundation or maintain stable, cooperative relationships with the National Assembly. Frequent general and regional elections further dampen national governance momentum. Presidential power peaks in the early months of the term but inevitably diminishes over time. While ambitious reform agendas may be pursued at the outset, presidents often become politically isolated in later stages, leaving governance defensive. This imbalance grows from the structural disharmony between the presidential term and the legislative election cycle.

The South Korean presidential systеm frequently results in a divided government, as presidential and legislative elections are held separately. Although this resembles the United States model, South Korea experiences more pronounced political conflicts and legislative gridlock due to its weak party systеm and internal factionalism. Clashes between presidential initiatives and legislative checks are routine. When compounded by internal divisions within the ruling party or declining presidential approval ratings, the president becomes increasingly politically isolated.

In response, presidents adopt strategies to circumvent or bypass legislative oversight. They issue executive orders, implement presidential decrees, or mobilize public opinion to bolster support (O’Donnell 1994). These approaches erode the democratic principle of separation of powers, weaken the legislature’s role, diminish horizontal accountability, and exacerbate the concentration of power in the president. Ultimately, the balance between executive and legislative authority collapses, and political conflict and social polarization intensify.

South Korean presidential systеm centers on a president who is directly elected by the people and endowed with substantial authority, assuming a high degree of accountability. However, this accountability is largely vertical between the president and voters, while horizontal mechanisms of oversight—such as the National Assembly, judiciary, and media—remain weak. When backed by high public approval, the president’s unilateral and authoritarian policy decisions face little effective resistance from the legislative branch or political parties. In effect, the separation of powers—fundamental to a functioning democracy—is severely undermined, putting democratic governance at risk (Park 2018).

Contemporary democracy depends on rational and transparent policy debates that transcend mere electoral participation. Nevertheless, in South Korea, such debates have become increasingly emotional and confrontational. When presidents use the media to pressure opposition forces or neutralize the authority of the National Assembly, political discourse degenerates from rational deliberation into polarized emotion. Song Ho-Keun (2025) describes this phenomenon as “the politics of emotional mobilization,” warning that the foundations of deliberative democracy are eroding and the democratic crisis is accelerating.

VI. Institutional Reform and the Task of Restoring Democracy

The democratic crisis in South Korea is complex, with actors, institutions, structures, and culture deeply intertwined. Approaches to institutional reform must avoid overly simplistic perspectives. In addressing the weaknesses of South Korean democracy, it is critical to distinguish between areas that can be reformed without constitutional revision, those that require constitutional amendments, and those that are unlikely to be resolved even through such changes.

Some areas of political reform can be achieved through the revision of existing laws without altering the current constitutional power structure. A representative example is electoral law reform. Restructuring the electoral systеm could be vital in improving proportionality between vote share and seat allocation, enhancing the accountability of elected officials, stabilizing the party systеm, and mitigating the winner-takes-all dynamic that currently dominates politics in South Korea.

Amending the Political Parties Act is also crucial. The excessive regulations embedded in this Act constrain the activities of political associations representing diverse regional stakeholders. Establishing a systеm that permits the creation of regional parties for participation in local elections could significantly contribute to political decentralization. If the Public Official Election Act and internal party regulations were revised to ensure more democratic nomination procedures and party governance, a vertically subordinate relationship between the president and the ruling party may be mitigated.

Meanwhile, certain structural issues require constitutional revision. The power distribution among the president, the prime minister, and the National Assembly is defined by the Constitution and cannot be altered without amending it. Similarly, core powers—such as authority in emergencies, military command, and budget formulation—are constitutionally mandated and require amendment for change. The misalignment of presidential and legislative election cycles is another issue that can only be solved through constitutional revision. Decisions about whether to hold these elections simultaneously or to treat legislative elections as a midterm assessment have a significant impact on power dynamics within the president’s affiliated party. Simultaneous elections would likely strengthen presidential authority while clarifying accountability between the president and the National Assembly. Midterm elections, while dispersing power, could increase the risk of prolonged political deadlock due to ambiguities in responsibility under a divided government. If the power structure were to shift significantly—toward a parliamentary, semi-presidential, or four-year presidential systеm with reelection—restoring public trust and achieving societal consensus would be essential.

Ultimately, institutional reform aimed at restoring democracy cannot be a linear process. Constitutional amendments and legislative reforms must proceed concurrently across multiple dimensions.

VII. Conclusion: A General Assessment of Democratic Crisis and Response Strategies

The crisis facing South Korean democracy results from a complex interaction of factors and cannot be attributed to any single cause. It cannot be fully understood through analyses focused solely on individual failings, such as the moral shortcomings or leadership deficiencies of specific presidents. Rather, the current situation is the product of the complex interplay between structural flaws in the presidential systеm, unique cultural traits of South Korean politics, and the capabilities of individual political leaders.

This article began with the question, “Is the democratic crisis facing South Korea stemming from the power structure or the incompetence of a leader?” In summary, this cannot be answered through a dichotomous framework. Although the South Korean presidential systеm formally adheres to the principle of separation among legal, adm?nistrative, and judicial powers, in practice, it produces a concentration of power in the presidency. This structure undermines the core democratic principle, weakens checks and balances, and results in isolated presidential decision-making and rigid governance.

This analysis has examined multiple layers of the crisis. These include the excessive concentration of power in the presidency, the breakdown of institutional oversight, the immaturity of party systеms oriented around individual presidents, recurring leadership crises, the misalignment of electoral cycles, and the expansion of emotional, political mobilization. Collectively, these elements illustrate the extent to which South Korean politics have diverged from democratic ideals.

A three-pronged strategy must be pursued. First, for areas that do not require constitutional amendments, democratizing political parties and institutionalizing citizen participation must be accomplished through voluntary reform efforts and legislative change. Second, for structural challenges necessitating constitutional reform, long-term social consensus and political leadership must guide a reconfiguration of the power structure. This includes redefining the relationship between the president and the National Assembly, evaluating alternative systеms such as parliamentary or semi-presidential models, aligning electoral cycles, and introducing mechanisms such as a vote of no confidence. Third, long-term strategies—such as civic education, the restoration of public deliberation, and political education—are necessary to address entrenched cultural bottlenecks. These include the absence of institutional forbearance and mutual respect, political polarization driven by negative partisanship, and emotionally charged political mobilization.

At its core, democracy is not secured by institutions alone but realized through political culture, civic behavior, and a continuous attunement between systеms and social reality. The democratic crisis in South Korea reflects the failure of such alignment in institutional and cultural terms. Overcoming this crisis requires comprehensive reform across structural, institutional, and cultural dimensions. ■

References

Bae, J. S., and Park, S. 2018. “Janus face: the imperial but fragile presidency in South Korea.” Asian Education and Development Studies 7, 4: 426-437.

Bermeo, N. 2016. “On Democratic Backsliding.” Journal of Democracy 27, 1: 5-19.

Dahl, R. A. 1989. Democracy and Its Critics. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Ganghof, S. 2023. “Justifying types of representative democracy: a response.” Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy 27, 2: 282-293.

Hur, Mi-yeon. 2017. “South Korea’s Blue House Scandal.” E-International Relations. February 21. https://www.e-ir.info/2017/02/21/south-koreas-blue-house-scandal/ (Accessed April 30, 2025)

Kellam, M., and Benasaglio Berlucchi, A. 2023. “Who’s to blame for democratic backsliding: populists, presidents or dominant executives?” Democratization 30: 1-21.

Linz, J. J. 1990. “The perils of presidentialism.” Journal of Democracy 1, 1: 51–69.

Mainwaring, S., and Shugart, M. S. 1997. Presidentialism and Democracy in Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

O'Donell, G. A. 1994. “Delegative democracy.” Journal of Democracy 5, 1: 55-69.

Samuels, D. J., and Shugart, M. S. 2010. Presidents, Parties, and Prime Ministers: How the Separation of Powers Affects Party Organization and Behavior. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shugart, M. S., and Carey, J. M. 1992. Presidents and Assemblies: Constitutional Design and Electoral Dynamics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Weyland, K. 2020. Populism: A Political-economic Approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Choi, Jang-Jip. 2003. Democracy after Democratization (in Korean). Seoul: Humanitas.

Choi, Kwang-Eun. 2025. The End of Presidential Systеm: Beyond Rebellion and Toward the 7th Republic (in Korean). Pyeongtaek: Jeongjikhan Mosaek.

Kwon, Hyeok Yong. 2023. “Democratic Backsliding in South Korea (in Korean).” Korean Political Science Review 57, 1: 33-58.

Park, Sanghoon. 2018. Blue House Government (in Korean). Seoul: Humanitas.

Song, Ho-Keun. 2025. The Anthology of Hostility Politics (in Korean). Paju: Nanam Publishing House.

Yoon, Yeo-joon, and Yoon-hyung Han. 2025. Qualification of the President (in Korean). Seoul: MG Channel.

The Crisis of South Korean Constitutional Democracy Before and After Martial Law

Jung Kim

Professor, University of North Korean Studies

Why did President Yoon Suk Yeol invoke the power to declare martial law? What are the implications of the series of impeachment motions initiated by the National Assembly and the series of requests for reconsideration exercised by the president before the declaration of martial law in relation to the constitutional order of South Korea? How did the National Assembly’s impeachment motion and the Constitutional Court’s ruling on the impeachment following the declaration of martial law affect democracy in South Korea?

I. Surface of the Constitutional Crisis: Collapse of the Norms of Mutual Toleration and Institutional Forbearance

The Constitution does not guarantee the proper functioning of democracy. Owing to the inherent conceptual gaps and ambiguous meanings common to all legal texts, constitutional provisions alone cannot prevent the transition from democracy to authoritarianism. In successful democracies, informal norms—although not stipulated in constitutional provisions—emerge from them and regulate political conduct. “Mutual tolerance” and “institutional forbearance” are two such informal norms essential to the stable functioning of democracy. Mutual tolerance refers to “the acknowledgment that political rivals exist as long as they abide by the Constitution and have the right to compete for power and govern society.” Institutional forbearance is defined as “the discreet exercise of legal authority” and reflects the recognition that “political power, even within legal boundaries, can render the existing systеm unstable.” When democracy is operating smoothly, the importance of these norms is less visible. However, once democracy begins to falter, violations of these norms become more evident. The failure of mutual tolerance and institutional forbearance to operate as regulatory norms of political behavior signals that democracy is in danger (Levitsky and Ziblatt 2018).

South Korean Constitution includes provisions that support the norm of institutional forbearance among political parties, such as the National Assembly’s right to initiate impeachment motions against high-ranking executive and judicial officials (Article 65 of the Constitution) and the president’s right to request reconsideration of legislation passed by the National Assembly (Article 53 of the Constitution). High-ranking officials in the executive and judiciary, including the president, are expected to exercise restraint in the use of their powers, aware that abuse or misuse could lead to impeachment. This expectation constitutes the constitutional norm of institutional forbearance. Similarly, the National Assembly is expected to wield legislative power with caution, understanding that the president may respond with a request for reconsideration when legislation introduces radical policy changes. These rights must not be invoked frequently if they are to fulfill their constitutional purpose (Helmke, Kroeger, and Paine 2022).

When either mechanism is overused, the inherent constitutional norm of institutional forbearance collapses, impeding the smooth functioning of democracy. If political parties breach this norm, they are said to have adopted a “constitutional hardball tactic.” Constitutional hardball tactic describes the weaponization of constitutional means to pursue partisan advantages, undermining institutional forbearance (Tushnet 2025).

South Korean Constitution also presupposes the norm of mutual tolerance. Violations of this norm include deferring National Assembly elections, which are scheduled every four years (Article 42 of the Constitution), or presidential elections, held every five years (Article 70 of the Constitution), as well as refusing to accept the results of such elections. Other violations include invoking the right to declare martial law without satisfying all required conditions (Article 77(1) of the Constitution), obstructing the National Assembly’s right to demand the lifting of martial law (Article 77(5) of the Constitution), or rejecting the Constitutional Court’s ruling on impeachment (Article 111 of the Constitution). Each of these actions implies a rejection of mutual tolerance, which is indispensable for South Korean democracy to function.

When political parties engage in behavior that breaches the norm of mutual tolerance, they are said to have adopted a “constitutional beanball tactic.” Constitutional beanball tactic refers to the weaponization of constitutional tools for partisan purposes, destroying mutual tolerance in the process (Shugerman 2019).

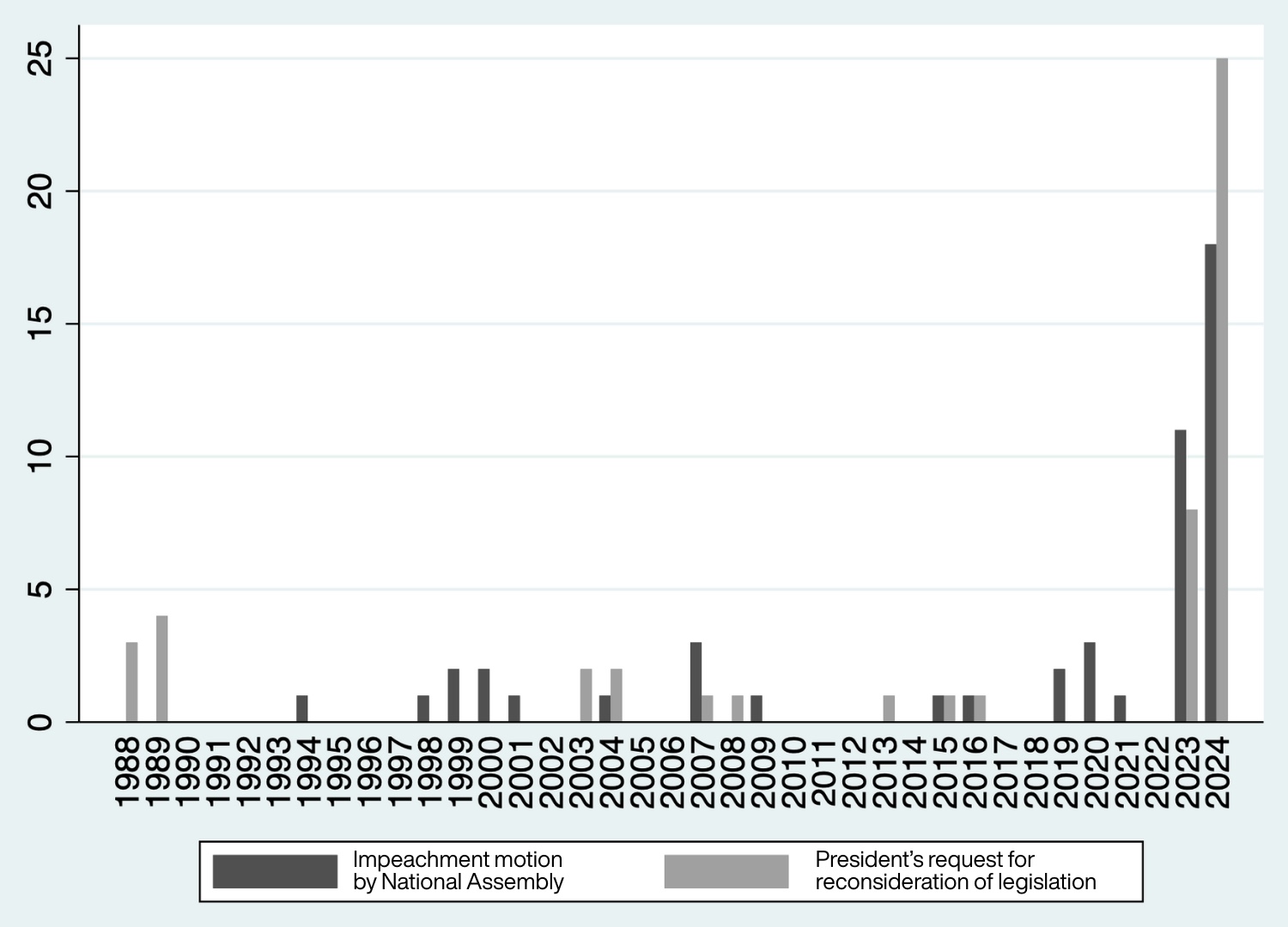

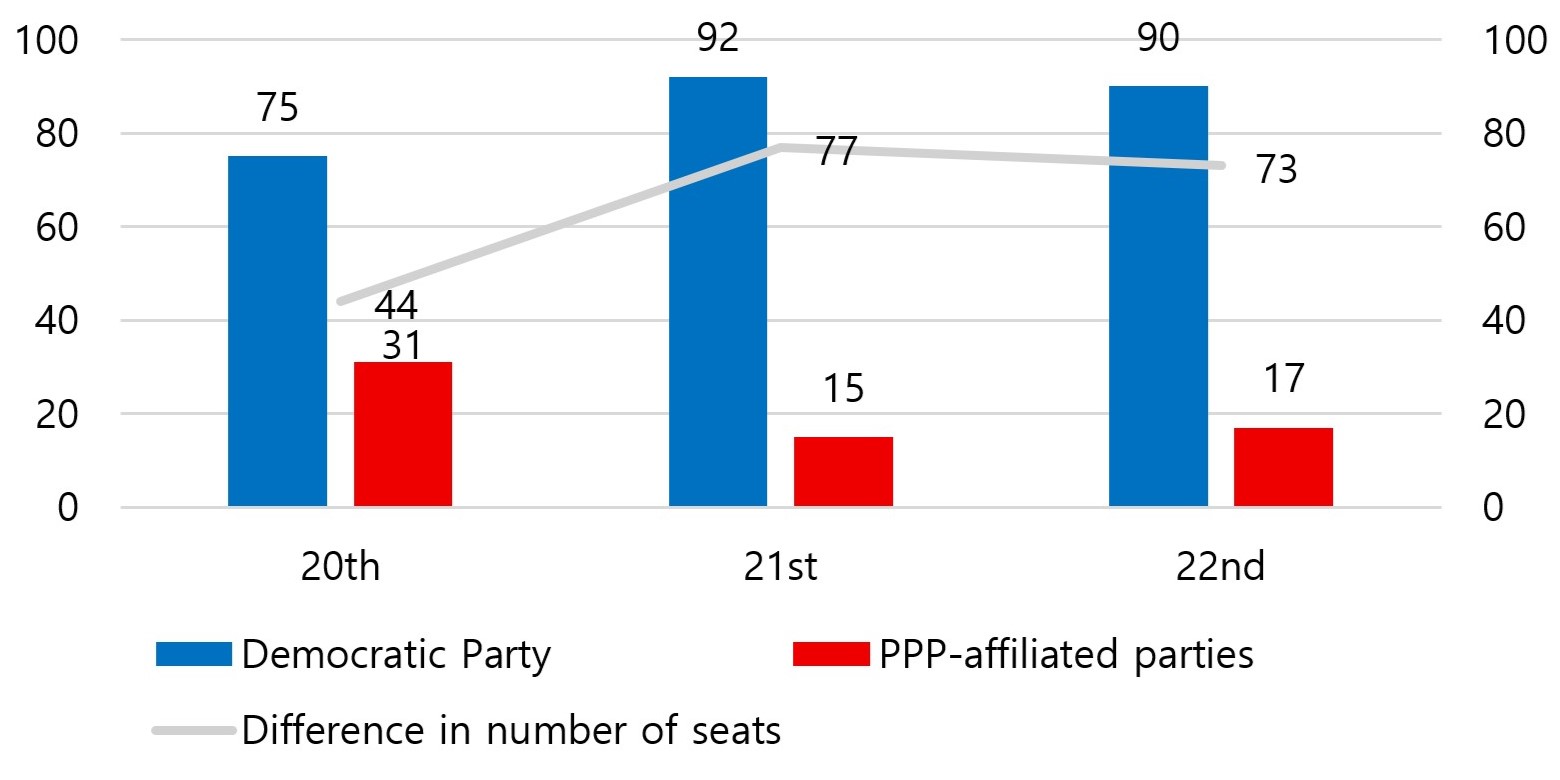

Figure 1. National Assembly Impeachment Motions and Presidential Vetoes since Democratization

Source: “Impeachment cases in the Republic of Korea” under the category “Impeachment,” Wikipedia. https://ko.wikipedia.org/wiki/탄핵#대한민국 (Accessed March 24, 2025); “Presidential Requests for Reconsideration” under the category “Reconsideration,” Wikipedia https://ko.wikipedia.org/wiki/거부권 (Accessed March 24, 2025)

Figure 1 presents a bar graph depicting the number of impeachment motions initiated by the National Assembly and presidential requests for reconsideration of legislation from 1988 to 2024. The dark gray bars indicate the number of impeachment motions, while the light gray bars represent the number of presidential reconsideration requests.

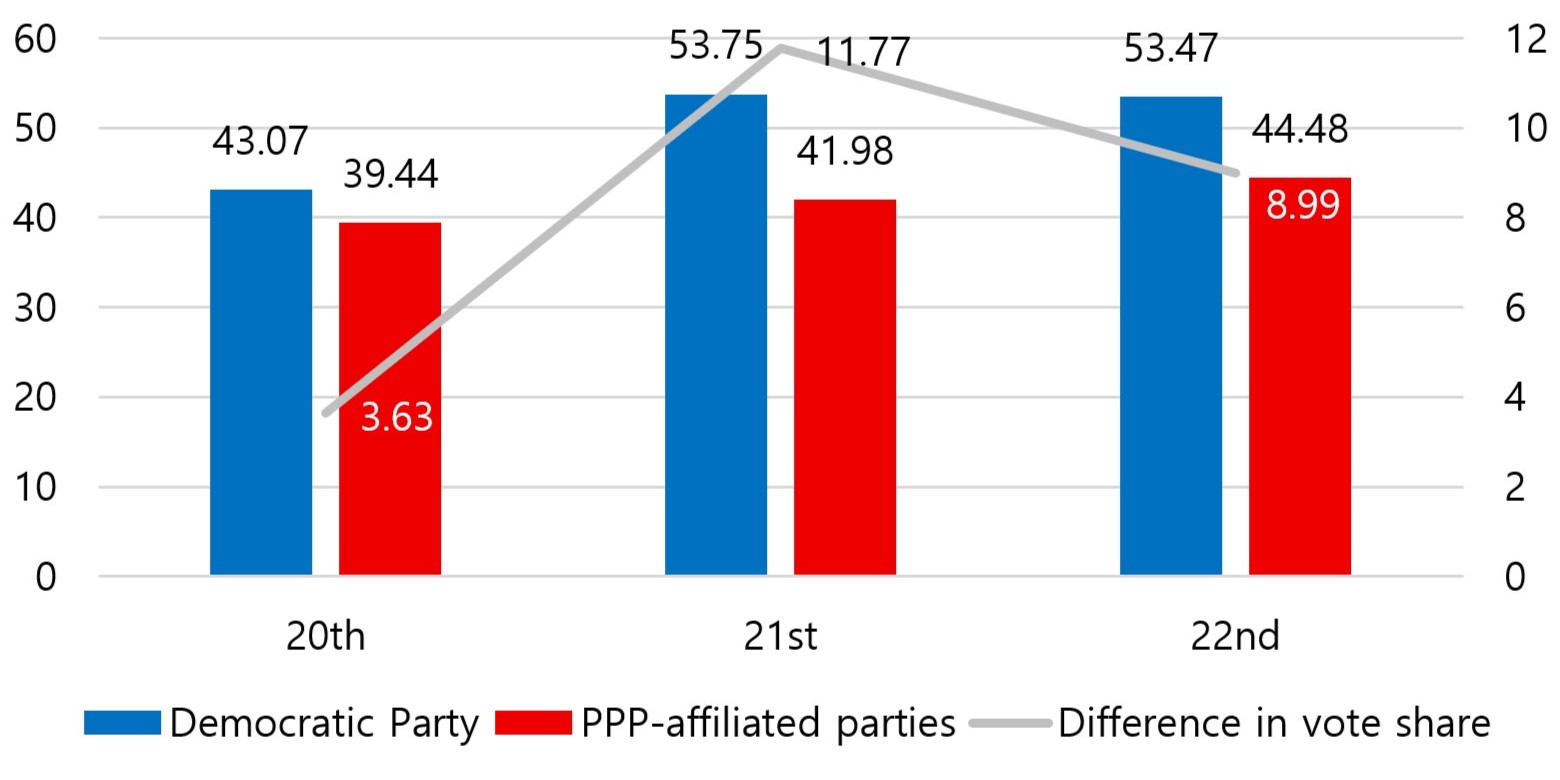

In the 33 years preceding President Yoon Suk Yeol’s inauguration, the National Assembly filed 20 impeachment motions against high-ranking executive and judicial officials, averaging approximately 0.6 per year. The highest annual count was three, recorded in 2007 and 2020. Conversely, during the two years and six months after President Yoon assumed office in 2022, the National Assembly submitted 29 impeachment motions against high-level executive and judicial officials. This represents a 20-fold increase compared to the previous annual average, rising to approximately 11.6 motions per year. Notably, there were 11 motions in 2023 and 18 in 2024.

Before President Yoon’s term, there had been 16 presidential requests for reconsideration of legislation. During his tenure, this number rose to 33. The previous average of approximately 0.5 requests per year surged to about 13.2 per year, marking a nearly 30-fold increase. Previously, the highest annual record was four cases in 1989; this record was surpassed with eight cases in 2023 and 25 in 2024.

As demonstrated by the dramatic increase in impeachment motions and reconsideration requests, it is difficult to deny that the opposition party and the president engaged in clear violations of institutional forbearance, resorting to what may be described as “over-utilization” of constitutional powers. By the time President Yoon invoked the power to declare martial law, one of the core constitutional norms essential to the healthy functioning of liberal democracy—institutional forbearance—had already significantly deteriorated.

In summary, President Yoon’s declaration of martial law resulted from an escalating confrontation between the opposition party, which controlled the National Assembly and initiated a series of impeachment motions against senior executive officials, and the president, who repeatedly exercised his authority to request reconsideration of legislative bills passed by the National Assembly. In response to the opposition’s “constitutional hardball tactics” involving excessive use of its impeachment power, the president resorted to “constitutional hardball tactics” by excessively invoking the right to request reconsideration. This stalemate continued over an extended period. The president’s declaration of martial law constituted a “constitutional beanball tactic” intended to break the prolonged political deadlock. In hopes of “restoring” democracy, President Yoon made a paradoxical decision to suspend constitutional order.

II. Deeper Layer of the Constitutional Crisis: Polarization of the National Narrative

In his address declaring martial law on December 3, 2024, President Yoon justified his “constitutional beanball tactic” as follows:

I declare martial law to protect the Republic of Korea from the threats of North Korean communist forces to immediately eradicate the unscrupulous pro-Pyongyang anti-state forces that pillage the freedom and happiness of our people and protect free constitutional order. For this, I will certainly eradicate such anti-state forces and the culprits of the country’s ruin who have committed evil acts up until now. It is an inevitable measure to guarantee the people's freedom, safety, and national sustainability against the actions of anti-state forces seeking to overthrow the systеm.

President Yoon labeled the opposition party as “anti-state forces” and targets to be eradicated. The norm of mutual toleration—one of the constitutional principles essential to the effective functioning of democracy—had already collapsed (Levitsky and Ziblatt 2018: 8).

A longer-term perspective is required to identify the root cause of the collapse of the constitutional norms of mutual toleration and institutional forbearance. Since democratization in 1987, South Korea transitioned from a political systеm that suppressed social conflict to one that exposed it. The discontent among citizens that had been previously suppressed began to surface while political elites selected issues to maximize votes. As repeated elections aligned public grievances with elite vote-maximization strategies, the party systеm gradually came to reflect society’s core political division. South Korea lacked traditional sources of political conflict found in premodern societies, such as ethnicity, race, language, or religion. Its modern political conflicts were also relatively moderate, including class, the rural–urban divide, environmental issues, and human rights. The traditional social cleavages around which political parties typically organize were largely absent. That allowed democratization to take root without major societal upheavals such as civil wars or large-scale unrest. However, the cost has been the current “pernicious polarization” of political parties (Song 2025).

Since the Roh Moo-hyun adm?nistration in 2003, partisan polarization between progressive and conservative parties has deepened to unprecedented levels. In the conservative narrative, citizens who supported reconciliation with North Korea were marginalized. In the progressive narrative, those who pursued rapprochement with Japan were excluded. Emotionally charged antagonism between the two camps became widespread.

When the discursive frameworks of political elites project emotionally charged narratives in which the progressive and conservative blocs refuse to recognize each other as legitimate, partisan competition in South Korea descends into pernicious polarization. When a progressive party assumes power, hostility among conservative supporters intensifies and vice versa. In such a democratic context, elections become emotionally driven confrontations rather than contests over policy. Consequently, when democratic norms clash with partisan interests, many political elites tend to adopt a “partisanship before democracy” approach. This trend signals the onset of democratic backsliding in South Korea (Kim 2023).

The conservative and progressive blocs in South Korea promote political narratives that combine a nationalist structure—pitting “in-group” against “out-group” with a populist structure that casts political elites as adversaries of the people. This fusion of populism and nationalism fragments the public into supporters of the “People Power Party” and the “Democratic Party,” reinforcing a partisan polarization of the nationalist narrative that turns citizens against one another. President Yoon’s decision to employ a constitutional beanball tactic occurred amid intensifying constitutional hardball tactics between the two blocs, rooted in polarized nationalist narratives that have solidified over more than half a century since the presidency of Roh Moo-hyun (Cho and Hur 2025).

III. Democratic Retrogression in the Republic of Korea: Partisan Divergence and Sorting

A more accurate understanding of national narrative polarization requires an analytical distinction between partisan divergence and sorting.

First, partisan divergence refers to growing heterogeneity between two ideological or affective blocs. Ideological partisan divergence indicates a widening policy gap between voters who support progressive parties and align with progressive values and voters who support conservative parties and align with conservative values. Affective partisan divergence refers to a widening emotional divide between voters who support progressive parties while holding a strong aversion toward conservative ones and voters who support conservative parties and feel a strong aversion toward progressive ones.

Conversely, partisan sorting refers to increasing homogeneity within a party that was previously internally divided ideologically or affectively. Ideological partisan sorting occurs when a growing proportion of progressive (or conservative) party voters also support corresponding ideological values. Affective partisan sorting occurs when a growing proportion of progressive (or conservative) party voters also hold a strong aversion toward the opposing party (Kim 2022).

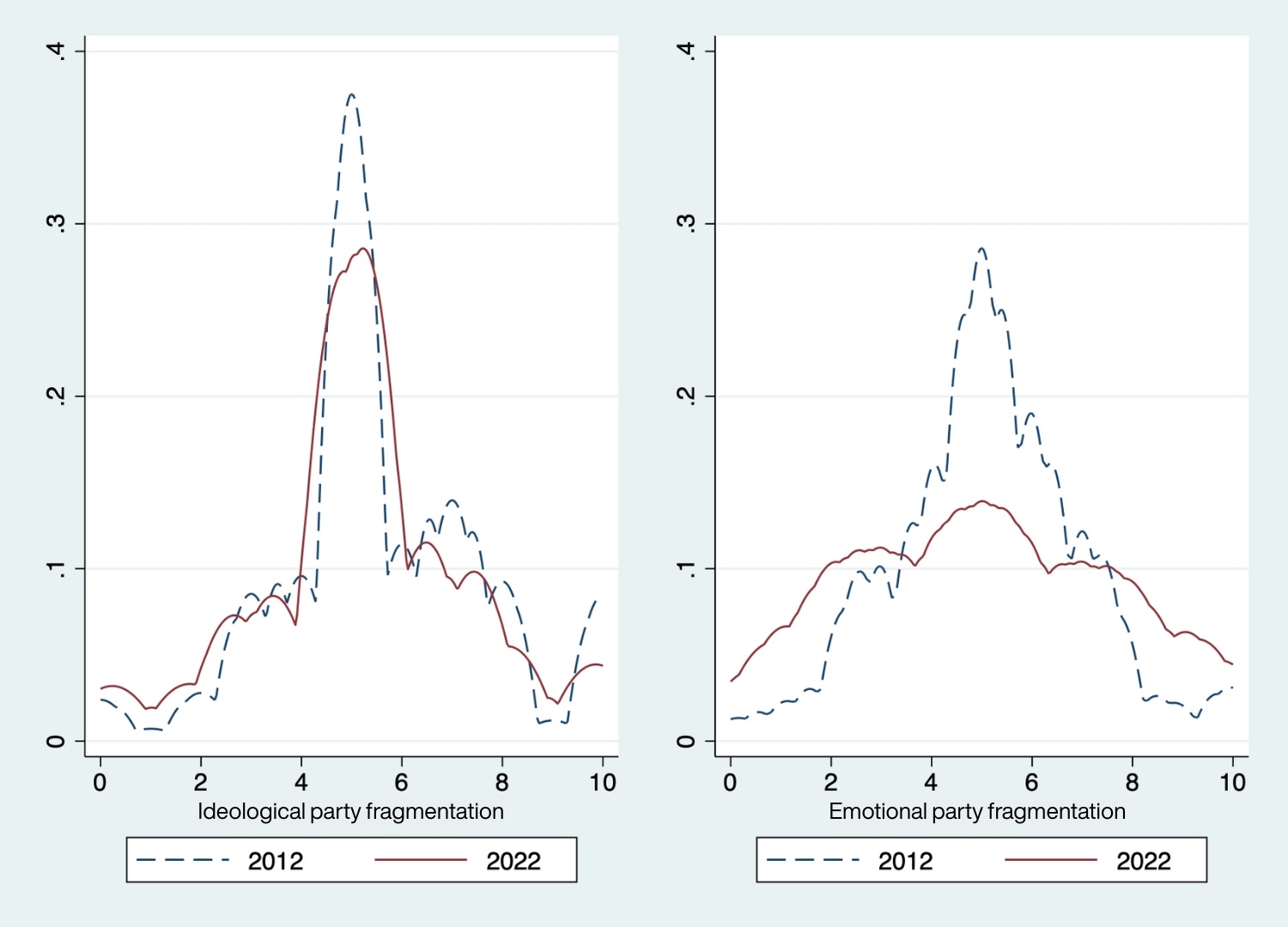

Figure 2 depicts the kernel density estimates of ideological and affective partisan divergence among South Korean voters in 2012 and 2022. In the diagram for ideological partisan divergence on the left, the horizontal axis ranges from 0, representing the highest level of agreement with progressive values, to 10, denoting the highest level of agreement with conservative values. In the diagram for affective partisan divergence on the right, the horizontal axis ranges from 0, indicating maximum aversion to the conservative party, to 10, indicating maximum aversion to the progressive party. The progressive party favorability score (0–10) is subtracted from the conservative party favorability score (0–10), and the resulting “partisan emotional score (-10–10)” is rescaled to a 0–10 scale.

Figure 2. Partisan Divergence among South Korean Voters in 2012 and 2022:

Kernel Density Estimation

Source: Ideological Partisan Divergence: East Asia Institute’s 2012 General Election and Presidential Election 7th Panel Study, Background Item 1, Question 1 & East Asia Institute’s 2022 General Election and Presidential Election 2nd Panel Survey, Background Item 6. Affective Partisan Divergence: East Asia Institute’s 2012 General Election and Presidential Election 7th Panel Study, Question 6-1-3 and 6-1-4 & East Asia Institute’s 2022 General Election and Presidential Election 2nd Panel Survey, Question 9-1 and 9-2. 2012 data https://kossda.snu.ac.kr/ (Accessed March 24, 2022)

Note: Ideological Partisan Divergence: 0 represents maximum agreement with progressive values; 10 indicates maximum agreement with conservative values. Affective Partisan Divergence: The party favorability score (0–10) is subtracted from the conservative party favorability score (0–10), and the resulting partisan emotional score (-10–10) is rescaled to a 0–10 scale. A score of 0 indicates maximum aversion to the conservative party, while 10 indicates maximum aversion to the progressive party.

The ideological partisan divergence shows that compared to 2012, the number of progressive-leaning voters increased slightly in 2022, while centrist voters decreased and conservative-leaning voters declined modestly. The affective partisan divergence shows that compared to 2012, the number of voters with negative sentiment toward the conservative party increased slightly in 2022, while the number of neutral voters decreased significantly, and those with negative sentiment toward the progressive party increased slightly. Statistical analysis confirmed that ideological and affective partisan divergence advanced over the decade. However, both distributions remain closer to a unimodal than a bimodal form. Although ideological and affective partisan divergence is visually evident among South Korean voters, the data do not indicate full-scale polarization.

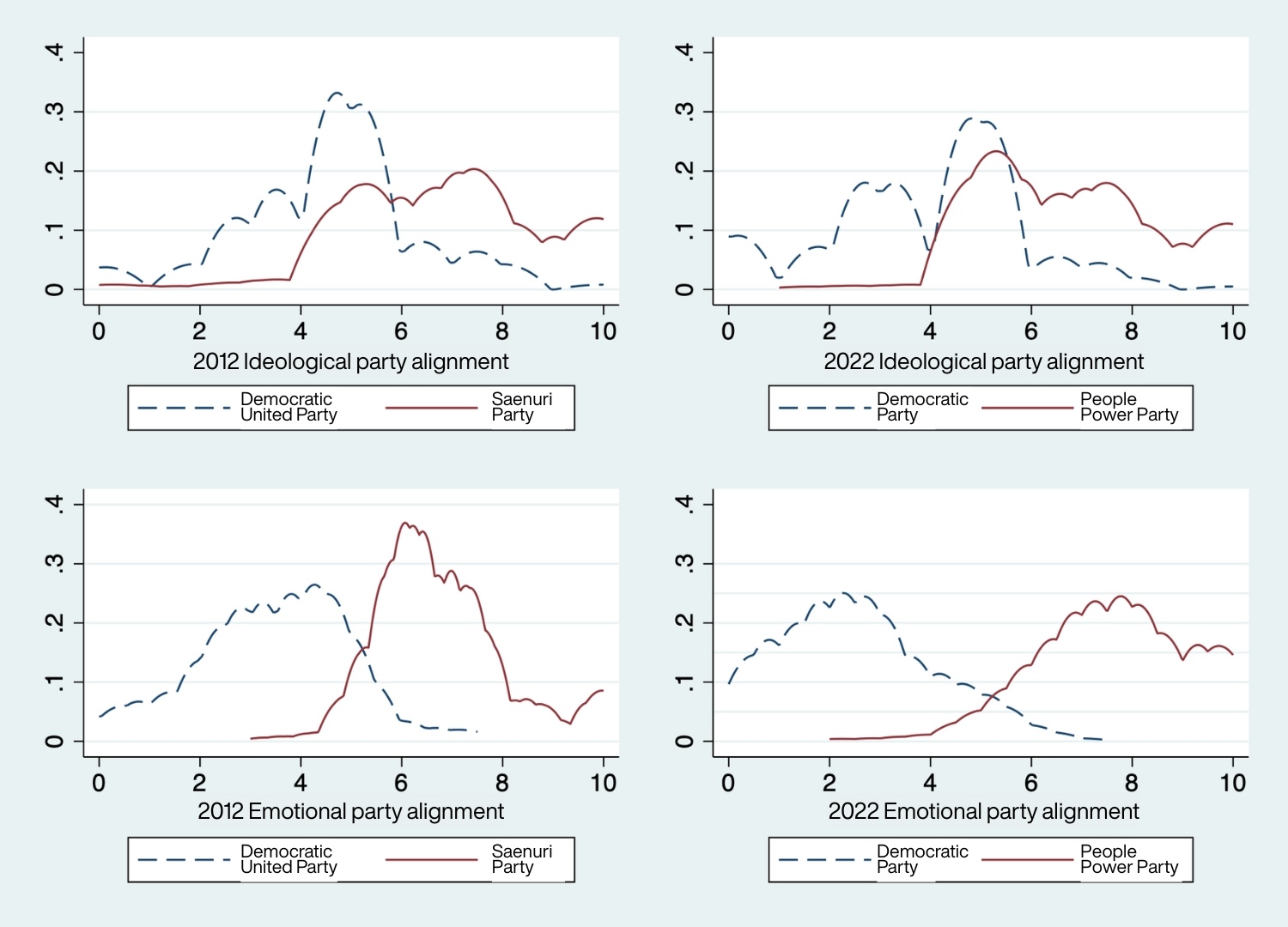

Figure 3. Partisan Sorting among South Korean Voters in 2012 and 2022:

Kernel Density Estimation

Source: Party identification: East Asia Institute’s 2012 General Election and Presidential Election 6th Panel Study Question & East Asia Institute’s 2022 General Election and Presidential Election 1st Panel Survey, Question 9. Others are identical to those in Figure 2. 2012 data: https://kossda.snu.ac.kr/ (Accessed April 24, 2022).

Figure 3 illustrates kernel density estimates of ideological and affective partisan sorting among South Korean voters in 2012 and 2022. In the diagram for ideological partisan sorting at the top, the horizontal axis ranges from 0, indicating maximum agreement with progressive values, to 10, indicating maximum agreement with conservative values. In the diagram for affective partisan sorting at the bottom, the horizontal axis ranges from 0, representing maximum aversion to the conservative party, to 10, representing maximum aversion to the progressive party.

The ideological partisan sorting shows that compared to 2012, the proportion of progressive-leaning voters within the progressive party increased in 2022, while the proportion of conservative-leaning voters declined. Among conservative party supporters, the proportion of conservative-leaning voters remained relatively stable, while the share of centrist-leaning voters increased and that of progressive-leaning voters decreased. Despite this compositional shift, there remains considerable overlap in the ideological distribution of voters supporting the progressive and conservative parties. Thus, ideological partisan sorting has not advanced significantly over the past decade.

The affective partisan sorting a more significant shift. Compared to 2012, the proportion of voters with a strong aversion to conservatives within the progressive party increased substantially in 2022, while the proportion of neutral voters and those with an aversion toward progressives declined markedly. Among conservative party supporters, the proportion of voters with a strong aversion to progressives also increased significantly, while neutral voters and those with an aversion toward conservatives declined. As a result of this shift, the overlap in emotional distribution between the two party supporter groups has decreased. This suggests that affective partisan sorting has progressed considerably over the past decade. Although ideological partisan sorting among South Korean voters seem to be far from polarization, affective partisan sorting is visibly nearing that threshold.

Ultimately, this analysis demonstrates that pernicious polarization is most clearly observed in affective partisan sorting. In other words, the primary targets of polarized national narratives projected by political elites are voters who support their respective parties and who have developed increasing animosity toward the opposing party over the past ten years. As the overlap between partisan voter groups diminishes and the emotional divide widens, party electoral strategies have shifted from persuading centrist voters to mobilizing their base supporters. The “median voter theorem” is no longer relevant, as parties diverge toward the ideological extremes instead of converging toward the center. This explains why the opposition’s constitutional hardball tactics and the president’s constitutional beanball tactics serve as effective vote-gathering strategies (Merrill III, Grofman, and Brunell 2024).

IV. Constitutional Democracy in South Korea after the Impeachment of President Yoon

Table 1. Public Support for Impeachment during the Trials of President Park Geun-hye and President Yoon Suk Yeol

|

|

Impeachment trial period for President Park Geun-hye |

Impeachment trial period for President Yoon Suk Yeol |

||||

|

|

Dec 2016, 2nd week |

Feb 2017, 2nd week |

Mar 2017, 1st week |

Dec 2024, 2nd week |

Feb 2025, 2nd week |

Mar 2025, 3rd week |

|

Overall |

81% |

79% |

77% |

75% |

60% |

58% |

|

Conservative |

66% |

63% |

50% |

46% |

25% |

26% |

|

Centric |

86% |

85% |

86% |

83% |

60% |

64% |

|

Progressive |

96% |

95% |

95% |

97% |

96% |

95% |

|

Ruling Party Supporter |

34% |

27% |

14% |

27% |

10% |

13% |

|

No Party Preference |

72% |

71% |

69% |

79% |

63% |

51% |

|

Supporter of Opposition Party |

99% |

96% |

97% |

97% |

98% |

96% |

Source: Gallup Report Daily Opinion Edition 239 (2nd week, December 2016), 245 (2nd week, February 2017), 248 (1st week, March 2017), 606 (2nd week, December 2024), 611 (2nd week, February 2025), 615 (3rd week, March 2025). https://www.gallup.co.kr/ (Accessed March 24, 2025)

Table 1 presents a comparison of public support for impeachment during President Yoon’s and President Park’s impeachment trial periods. During President Park’s impeachment, support stood at 81% in December 2016, 79% in February 2017, and 77% in March 2017. Support for President Yoon’s impeachment was 75% in December 2024, 60% in February 2025, and 58% in March 2025. Compared to the trend during President Park’s proceedings, public support for President Yoon’s impeachment was approximately 20 percentage points lower in absolute terms. Among conservative voters, support for impeachment declined by roughly 16 percentage points in the four months following Park’s impeachment motion, while support for Yoon’s impeachment dropped by about 20 percentage points.

Conversely, support for impeachment among progressive voters remained stable during the four months after the impeachment motion, shifting only from 96% to 95% for President Park and from 97% to 95% for President Yoon. These patterns suggest that many conservative voters may have engaged in “preference falsification” when initially expressing their opinion on impeachment right after the declaration of martial law. As the conservative bloc organized mass rallies, triggering an information cascade, conservative voters increasingly and openly adopted the principle of “partisanship first, democracy later” as their behavioral norm. President Yoon’s strategic assault on the Constitution lowered the transaction costs associated with a far-right shift among conservative voters and intensified the polarization of national narratives. Emotional party alignment clearly served as the political foundation for this dynamic.

From unfounded allegations of electoral fraud used to reject election outcomes to the dismissal of impeachment rulings under claims of a “leftist judicial cartel,” conservative constitutional breakdown strategies aimed at dismantling democratic institutions have accelerated. The refusal of conservative voters to accept the Constitutional Court’s impeachment ruling and the Supreme Court’s potential criminal verdict on charges of insurrection against the president presents a direct threat to democracy, compelling the conservative party to follow suit. With President Yoon acting as a mediator, conservative voters and the conservative party appear unable to resist the allure of a “Faustian bargain.”

The resulting political climate has created conditions in which conservative and progressive parties face reduced constraints when expressing their discontent through violence. The mutual escalation of constitutional hardball tactics by both blocs has already eroded the norm of institutional forbearance. President Yoon’s use of constitutional beanball tactics has further diminished the perceived political costs of abandoning the norm of mutual toleration. Ultimately, President Yoon’s tactical decision and its longer-term effects have made democratic backsliding in South Korea appear all but inevitable. ■

References

Cho, Joan E., and Aram Hur. 2025. “The Perils of South Korean Democracy.” Journal of Democracy 36, 2: 38-46.

Helmke, Gretchen, Mary Kroeger, and Jack Paine. 2021. “Democracy by Deterrence: Norms, Constitutions, and Electoral Tilting.” American Journal of Political Science 66: 267-534.

Kim, Jung. 2023. “South Korea.” in Rachel Beatty Riedl et al. (eds.) Opening Up Democratic Space. Original Research: Case Studies. Washington, D. C.: USAID.

Levitsky, Steven and Daniel Ziblatt. 2018. How Democracies Die. New York: Crown.

Merrill III, Samuel, Bernard Grofman, and Thomas L. Brunell. 2024. How Polarization Begets Polarization: Ideological Extremism in the US Congress. New York: Oxford University Press.

Shugerman, Jed Handelsman. 2019. “Hardball vs. Beanball: Identifying Fundamentally Antidemocratic Tactics.” Columbia Law Review 119: 85-122.

Tushnet, Mark. 2025. “Constitutional Hardball.” in Richard Bellamy and Jeff King (eds.), Cambridge Handbook of Constitutional Theory. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kim, Jung. 2022. “Political Polarization and Vote Choice in South Korea: Evidence from the 2012 and 2022 Presidential Elections.” (in Korean) Korea & World Politics 38: 169-198.

Song, Ho-geun. 2025. The Anthology of Hostility Politics (in Korean). Paju: Nanam Publishing House.

South Korean Political Elites and Democratic Backsliding

Sunkyoung Park

Professor, Korea University

I. Introduction

Where does the current democratic crisis in the Republic of Korea originate? Is it rooted in institutional flaws within the power structure, such as the presidential or electoral systеms? Is it a result of shifts in citizen preferences, such as affective polarization or the erosion of democratic norms? This article argues that the primary focus should not be institutional flaws or citizen preferences but the preferences and behaviors of political elites and the incentive structures that constrain them to examine the causes of the democratic crisis in South Korea that emerged following the declaration of martial law on December 3.

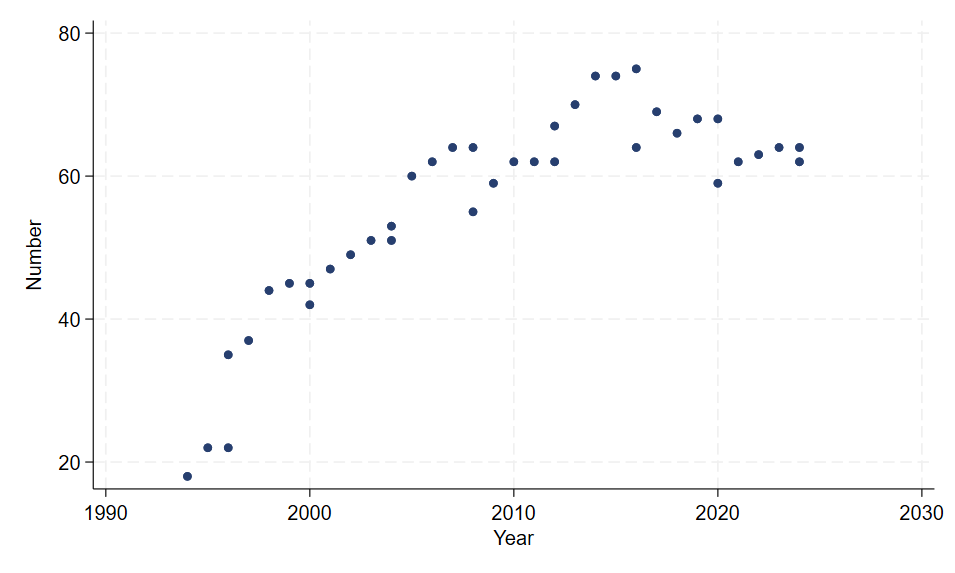

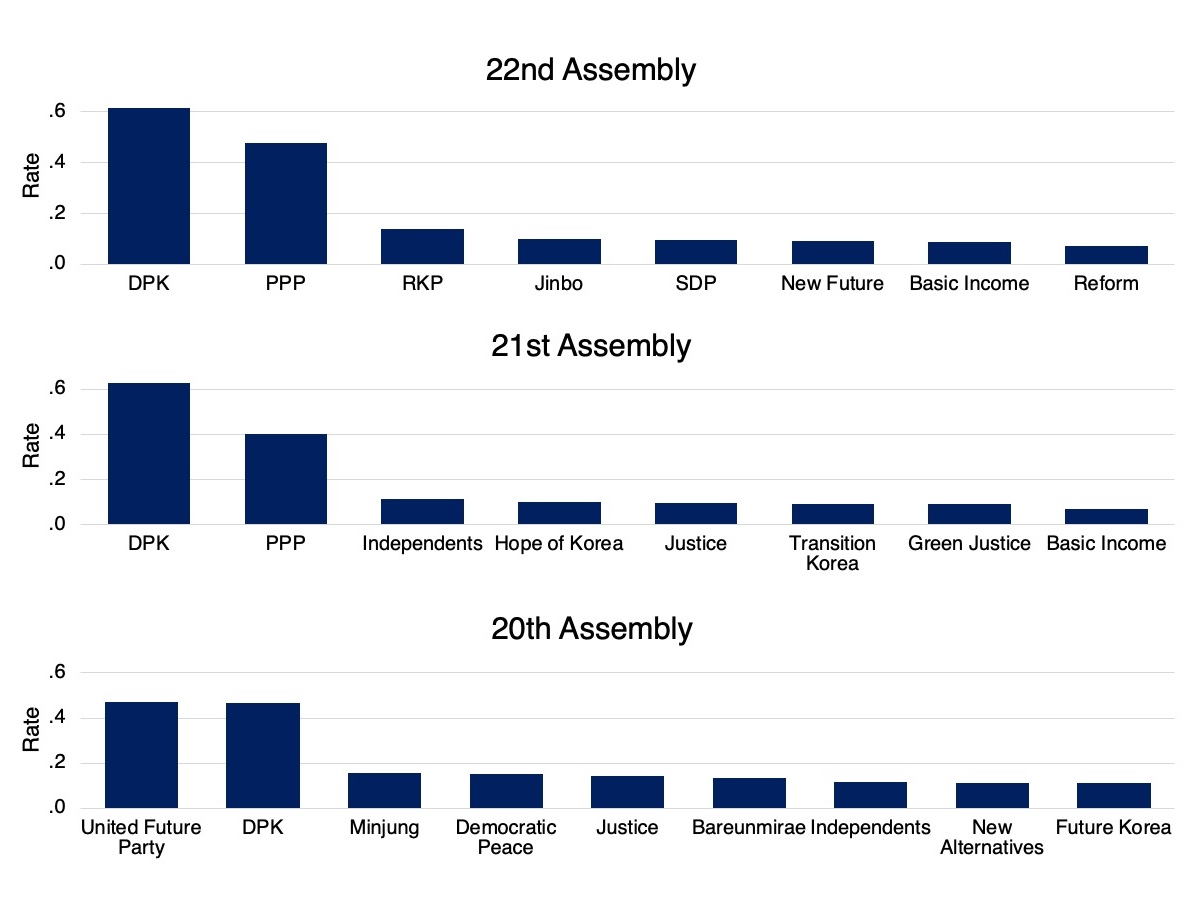

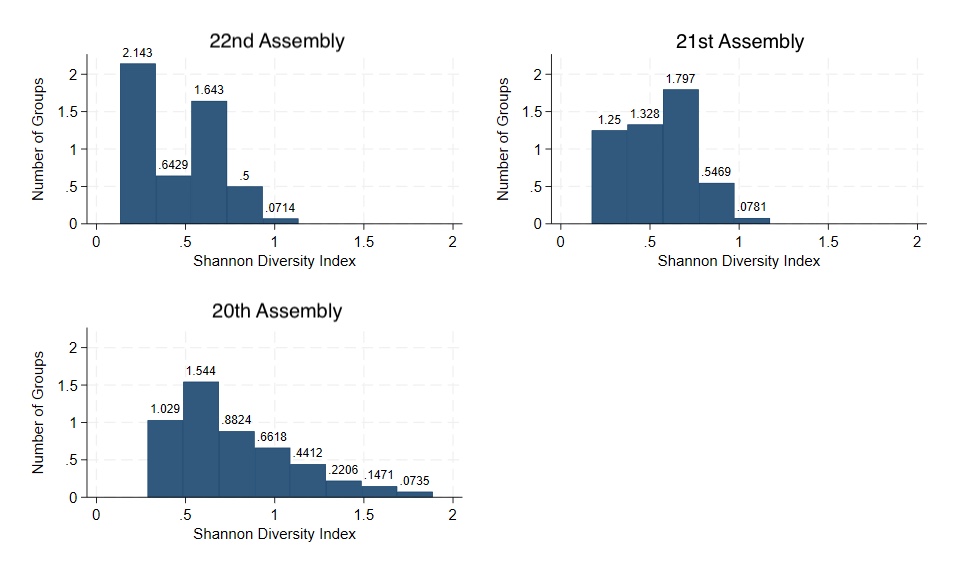

This argument does not deny the existence of institutional flaws in the power or electoral systеms. Such flaws have functioned as structural constants in the politics of South Korea since 1987. However, the current situation is best understood as a crisis precipitated not by these flaws but by the failure to overcome them or by political elites who have exploited them.