연구센터

아시아 민주주의 협력

[ADRN Working Paper] Horizontal Accountability and Democratic Resilience: The Case of South Korea in Comparative Perspective

- 2023-05-11

- Jung Kim

ISBN 979-11-6617-605-0 95340

1. Introduction

This study describes de jure horizontal accountability mechanisms and examines the de facto horizontal accountability performance of South Korea for the last two decades since 2000, putting the country in the comparative context of the third-wave democratizers.

It shows that South Korea optimally designed its inter-branch checks-and-balances mechanisms on parchment by setting legislative and judicial constraints on the executive in an unbiased manner. It also reveals the perilous discrepancies between de jure horizontal accountability mechanisms and de facto horizontal accountability performance by detecting earlier deterioration of and later reversal of inter-branch accountability outcomes in the country. Finally, it confirms that the oscillation of horizontal accountability between corrosion and restoration correlates with the fluctuation of democracy between erosion and resilience in South Korea.

In the next section, this study introduces a variety of empirical indicators to measure executive, legislative, and judicial powers in order to describe South Korea’s de jure horizontal accountability mechanisms and compare them with other third-wave democratizers. The penultimate section utilizes several empirical measures to estimate South Korea’s de facto horizontal accountability performance and the impact on the quality of democracy. In conclusion, it summarizes the main findings and suggests research agendas for the subsequent study.

2. De jure Horizontal Accountability: South Korea in Comparative Context

In this section, I introduce empirical indicators for the de jure horizontal accountability mechanisms of South Korea. As a template to evaluate the parchment configuration of horizontal accountability mechanisms, I use the following data sources to measure the strength of the constitutional inter-branch checks and balances provisions. For executive power or constitutional endowments of executive actions, I employ the ‘executive power index’ from Constitute, which ranges from 0 to 1 and captures the presence or absence of seven significant aspects of executive lawmaking: (1) the power to initiate legislation; (2) the power to issue decrees; (3) the power to initiate constitutional amendments; (4) the power to declare states of emergency; (5) veto power; (6) the power to challenge the constitutionality of legislation; and (7) the power to dissolve the legislature. The index score is the mean of the seven binary elements, with higher numbers indicating more executive power and lower numbers indicating less executive power (Elkins, Ginsburg, and Melton, 2023).

South Korea’s executive power index score is 0.43, which reflects its constitutional provisions of (1) the power to initiate legislation,[1] (2) the power to issue decrees,[2] (3) the power to initiate constitutional amendments,[3] (4) the power to declare a state of emergency[4] and (5) veto power,[5] but no constitutional provisions of (6) the power to challenge the constitutionality of legislation and (7) the power to dissolve the legislature.

For legislative power or constitutional endowments of legislative constraints on executive actions, I employ the ‘legislative power index’ from the Handbook of National Legislature, which ranges from 0 to 1 and captures the presence or absence of thirty-two important aspects of legislative constraints on the executive actions. The index score is simply the mean of the following thirty-two binary elements, with higher numbers indicating more legislative power and lower numbers indicating less legislative power (Fish and Kroenig, 2009):

(a) the legislature’s influence over the executive, which includes (1) whether the legislature alone, without the involvement of any other agencies, can impeach the president or replace the prime minister; (2) whether ministers may serve simultaneously as members of the legislature; (3) whether the legislature has powers of summons over executive branch officials and hearings with executive branch officials testifying before the legislature or its committees are regularly held; (4) whether the legislature can conduct independent investigation of the chief executive and the agencies of the executive; (5) whether the legislature has effective powers of oversight over the agencies of coercion; (6) whether the legislature appoints the prime minister; (7) whether the legislature’s approval is required to confirm the appointment of ministers or the legislature itself appoints ministers; (8) whether the country lacks a presidency entirely or there is a presidency, but the president is elected by the legislature; (9) whether the legislature can vote no confidence in the government;

(b) the legislature’s institutional autonomy, which includes (10) whether the legislature is immune from dissolution by the executive; (11) whether any executive initiative on legislation requires ratification or approval by the legislature before it takes effect; (12) whether laws passed by the legislature are veto-proof or essentially veto-proof; (13) whether the legislature’s laws are supreme and not subject to judicial review; (14) whether the legislature has the right to initiate bills in all policy jurisdictions; (15) whether the expenditure of funds appropriated by the legislature is mandatory; (16) whether the legislature controls the resources that finance its internal operation and provide for the perquisites of its members; (17) whether members of the legislature are immune from arrest and/or criminal prosecution; and (18) whether all members of the legislature are elected;

(c) the legislature’s specified powers, which include (19) whether the legislature alone, without the involvement of any other agencies, can change the Constitution; (20) whether the legislature’s approval is necessary for the declaration of war; (21) whether the legislature’s approval is necessary to ratify treaties with foreign countries; (22) whether the legislature has the power to grant amnesty; (23) whether the legislature has the power of pardon; (24) whether the legislature reviews and has the right to reject appointments to the judiciary or the legislature itself appoints members of the judiciary; (25) whether the chairman of the central bank is appointed by the legislature; (26) whether the legislature has a substantial voice in the operation of the state-owned media;

(d) the legislature’s institutional capacity, which includes (27) whether the legislature is regularly in session; (28) whether each legislator has a personal secretary; (29) whether each legislator has at least one non-secretarial staff member with policy expertise; (30) whether legislators are eligible for re-election without any restriction; (31) whether a seat in the legislature is an attractive enough position that legislators are generally interested in and seek re-election; and (32) whether the re-election of an incumbent legislator is common enough that at any given time the legislature contains a significant number of highly experienced members.

South Korea’s legislative power index score is 0.59, which reflects its constitutional provisions for:

(a) the legislature’s influence over the executive about (2) whether ministers may serve simultaneously as members of the legislature,[6] (3) whether the legislature has powers of summons over executive branch officials and hearings with executive branch officials testifying before the legislature or its committees are regularly held,[7] (4) whether the legislature can conduct an independent investigation of the chief executive and the agencies of the executive,[8] and (5) whether the legislature has effective powers of oversight over the agencies of coercion;

(b) the legislature’s institutional autonomy about (10) whether the legislature is immune from dissolution by the executive, (11) whether any executive initiative on legislation requires ratification or approval by the legislature before it takes effect,[9] (14) whether the legislature has the right to initiate bills in all policy jurisdictions, (15) whether the expenditure of funds appropriated by the legislature is mandatory, (16) whether the legislature controls the resources that finance its internal operation and provide for the perquisites of its members, and (18) whether all members of the legislature are elected;[10]

(c) the legislature’s specified powers about (20) whether the legislature’s approval is necessary for the declaration of war,[11] (21) whether the legislature’s approval is necessary to ratify treaties with foreign countries,[12] and (24) whether the legislature reviews and has the right to reject appointments to the judiciary or the legislature itself appoints members of the judiciary;[13]

(d) the legislature’s institutional capacity about (27) whether the legislature is regularly in session,[14] (28) whether each legislator has a personal secretary, (29) whether each legislator has at least one non-secretarial staff member with policy expertise, (30) whether legislators are eligible for re-election without any restriction; (31) whether a seat in the legislature is an attractive enough position that legislators are generally interested in and seek re-election; and (32) whether the re-election of an incumbent legislator is common enough that at any given time the legislature contains a significant number of highly experienced members.

For judicial power or constitutional endowments of judicial constraints on executive actions, I employ the ‘judicial power index’ from Constitute, which ranges from 0 to 1 and captures the presence or absence of twelve important aspects of judicial constraints on executive actions. The index score is simply the mean of the twelve binary elements, with higher numbers indicating more judicial power and lower numbers indicating less judicial power (Elkins, Ginsburg, and Melton, 2023):

(a) the judicial independence, which includes (1) whether the Constitution contains an explicit statement of judicial independence; (2) whether the Constitution provides that judges have lifetime appointments; (3) whether appointments to the highest court involve either a judicial council or two (or more) actors; (4) whether removal is prohibited or limited so that it requires the proposal of a supermajority vote in the legislature, or if only the public or judicial council can propose removal and another political actor is required to approve such a proposal; (5) whether removal is explicitly limited to crimes and other issues of misconduct, treason, or violations of the Constitution; and (6) whether judicial salaries are protected from reduction.

(b) the judicial capacity, which includes (7) whether the Constitution provides for judicial review; (8) whether courts have the power to supervise elections; (9) whether any court has the power to declare political parties unconstitutional; (10) whether judges play a role in removing the executive, for example in impeachment; (11) whether any court has any ability to review declarations of emergency; and (12) whether any court has the power to review treaties.

South Korea’s judicial power index score is 0.58, which reflects its constitutional provisions for:

(a) the judicial independence, which includes (1) whether the Constitution contains an explicit statement of judicial independence,[15] (3) whether appointments to the highest court involve either a judicial council or two (or more) actors,[16] (5) whether removal is explicitly limited to crimes and other issues of misconduct, treason, or violations of the Constitution, and (6) whether judicial salaries are protected from reduction.[17]

(b) the judicial capacity, which includes (7) whether the Constitution provides for judicial review,[18] (9) whether any court has the power to declare political parties unconstitutional,[19] (10) whether judges play a role in removing the executive;[20] but no constitutional provisions about (8) whether courts have the power to supervise elections, (11) whether any court has any ability to review declarations of emergency, and, (12) whether any court has the power to review treaties.

To put South Korea’s executive, legislative, and judicial power index score in a comparative context, I construct a sample of eighteen fellow third-wave democratizers from (1) East and Southeast Asia: Indonesia (1999), Mongolia (1991), Philippines (1988), South Korea (1988), Taiwan (1996), and Thailand (1998); (2) Central and Eastern Europe: Bulgaria (1991), Czech Republic (1990), Hungary (1990), Poland (1990); Romania (1991), and Slovak Republic (1994); and (3) Central and South America: Argentina (1984), Brazil (1987), Chile (1990), Colombia (1991), Mexico (1996), and Peru (1981).[21]

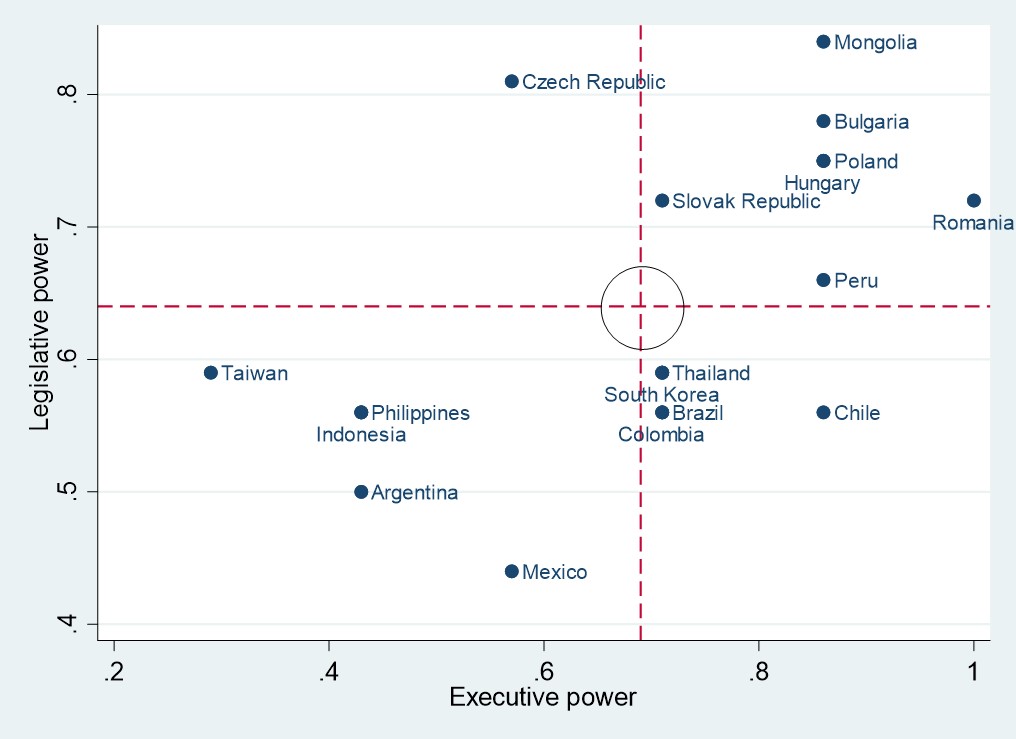

Figure 1 illustrates a scatterplot in which the horizontal axis shows the executive power index scores of the eighteen third-wave democratizers, and the vertical axis shows the legislative power index scores of the eighteen third-wave democratizers. Each dotted line indicates the mean value of each power index score. In the upper-right corner, where the imperial president meets the recalcitrant assembly, Mongolia, Bulgaria, Poland, Hungary, and Romania are located. Taiwan, Argentina, and Mexico are in the lower-left corner, where the non-dominant executive meets the subservient legislature. While Chile adopts a constitutional design that combines the imperial president with the subservient legislature, the Czech Republic employs a constitutional design that blends the non-dominant executive with the recalcitrant assembly. Regarding de jure accountability, South Korea seems to have one of the most workable executive-legislative inter-branch checks and balances mechanisms among the eighteen third-wave democratizers.

Figure 1. Executive and Legislative Power Index Scores in 18 Third-wave Democratizers

Source: Elkins, Ginsburg, and Melton 2023; Fish and Kroenig 2009

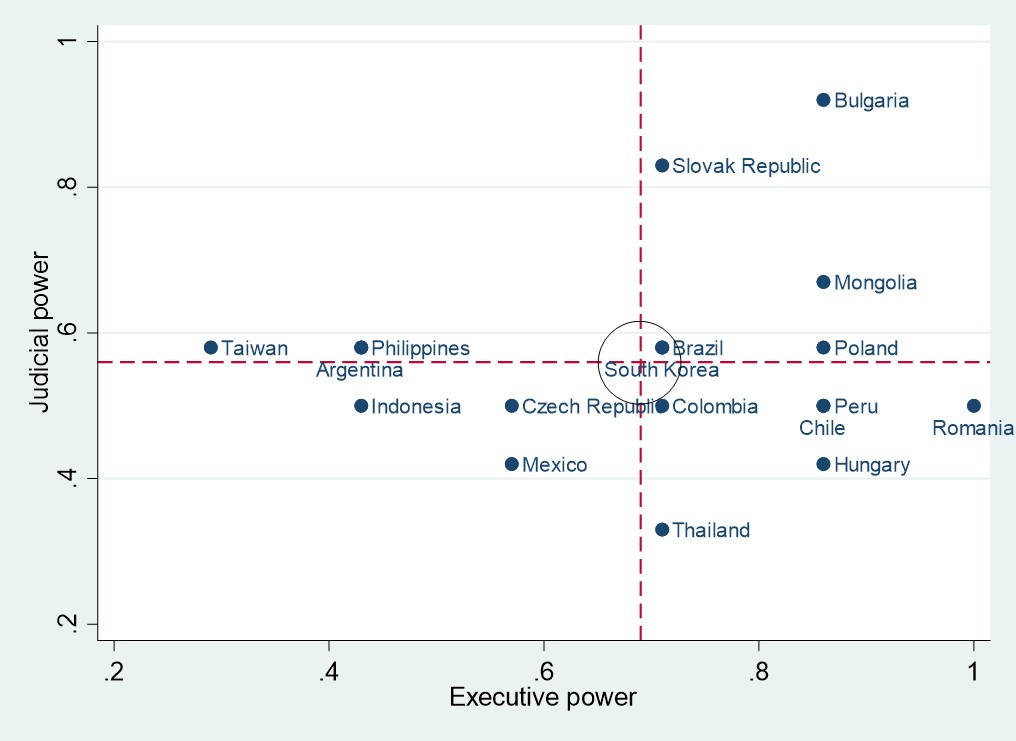

Figure 2 shows a scatterplot in which the horizontal axis represents the executive power index scores of the eighteen third-wave democratizers and the vertical axis indicates the judicial power index scores of the eighteen third-wave democratizers. Each dotted line indicates the mean value of each power index score. Bulgaria is in the upper-right corner, where the imperial president meets the recalcitrant court. Indonesia and Mexico are in the lower-left corner, where the non-dominant executive meets the subservient tribunal. While Romania, Hungary, and Thailand employ the constitutional design that combines the imperial president with the subservient tribunal, Taiwan adopts a constitutional design that blends the non-dominant executive with the recalcitrant court. Regarding de jure accountability, South Korea seems to have one of the most workable executive-judicial inter-branch checks and balances mechanisms among the eighteen third-wave democratizers.

Figure 2. Executive and Judicial Power Index Scores in 18 Third-wave Democratizers

Source: Elkins, Ginsburg, and Melton 2023

3. De facto Horizontal Accountability: South Korea in Comparative Context

In this section, I present empirical indicators for de facto horizontal accountability performance and its impact on the quality of democracy in South Korea. As a template to assess the actual outcomes of horizontal accountability mechanisms and the quality of democracy, I use the following data sources for measurement. For de facto horizontal accountability performance, I employ the ‘horizontal accountability index’ from Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem), which ranges from 0 to 1 and captures to what extent the ideal of horizontal government accountability is achieved by aggregating the following indicators: (1) the V-Dem judicial constraints the executive index; (2) the V-Dem legislative constraints on the executive index, and (3) V-Dem other state bodies (comptroller general, general prosecutor, or ombudsman) constraints on the executive index. The higher numbers indicate more de facto horizontal accountability and lower numbers denote less de facto horizontal accountability (Luhrmann, Marquardt, and Mechkova 2020).

For the quality of democracy, I employ the ‘liberal democracy index’ from V-Dem, which ranges from 0 to 1 and captures to what extent the ideal of liberal democracy is achieved. The higher numbers indicate higher quality of democracy, and lower numbers indicate lower quality of democracy (Coppedge et al., 2020).

For the convenience of presentation, I calculate the mean values of five-year intervals since 2000 for each index score of the eighteen third-wave democratizers. South Korea’s horizontal accountability index scores are as follows: (1) 2000-2004: 0.925; (2) 2005-2009: 0.902; (3) 2010-2014: 0.865; and (4) 2015-2019: 0.933. South Korea’s liberal democracy index scores are as follows: (1) 2000-2004: 0.772; (2) 2005-2009: 0.738; (3) 2010-2014: 0.649; and (4) 2015-2019: 0.722.

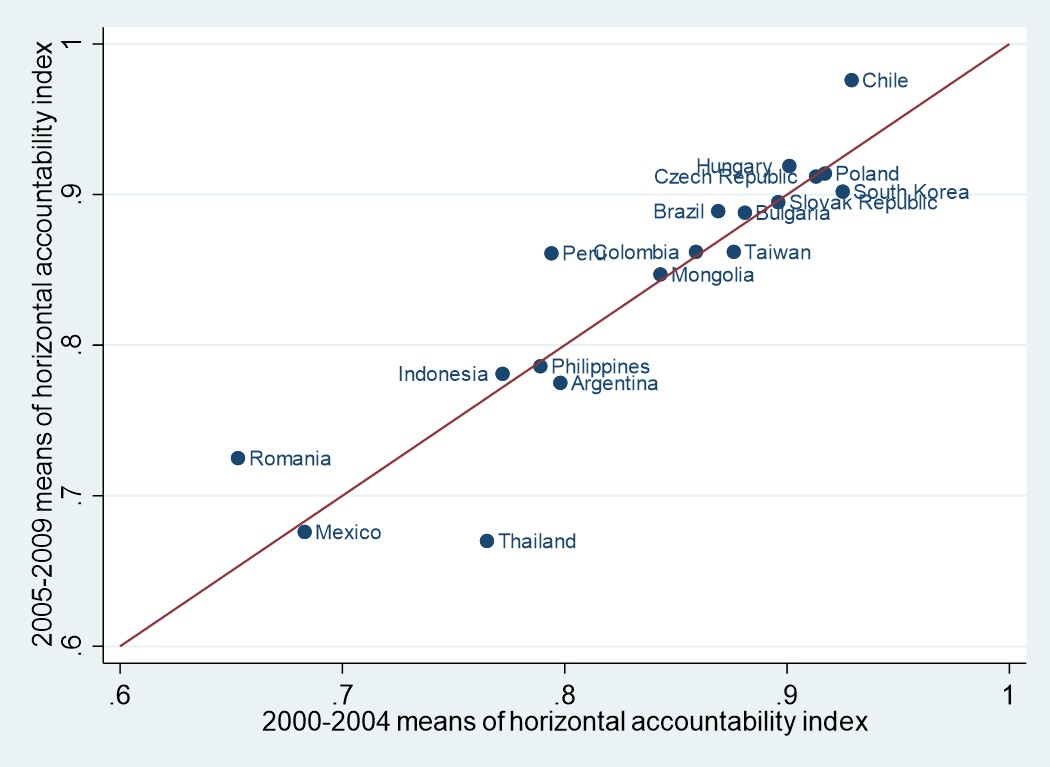

Figure 3. Horizontal Accountability Index Scores of 18 Third-wave Democratizers, 2000-2004 versus 2005-2009

Source: V-Dem (https://www.v-dem.net/data/)

Figure 3 illustrates a scatterplot in which the horizontal axis shows the 2000-2004 mean values of the horizontal accountability index scores of the eighteen third-wave democratizers, and the vertical axis represents the 2005-2009 mean values of horizontal accountability index scores of the eighteen third-wave democratizers. If a country is on the left side of the 45-degree line, its de facto horizontal accountability is improved. If a country is on the right side of the 45-degree line, its de facto horizontal accountability deteriorates. Chile, Peru, and Romania represent the former, whereas South Korea, Taiwan, Argentina, and Thailand typify the latter. Regarding de facto accountability, South Korea seems to be one of the modest horizontal accountability erosion cases among the eighteen third-wave democratizers during the period.

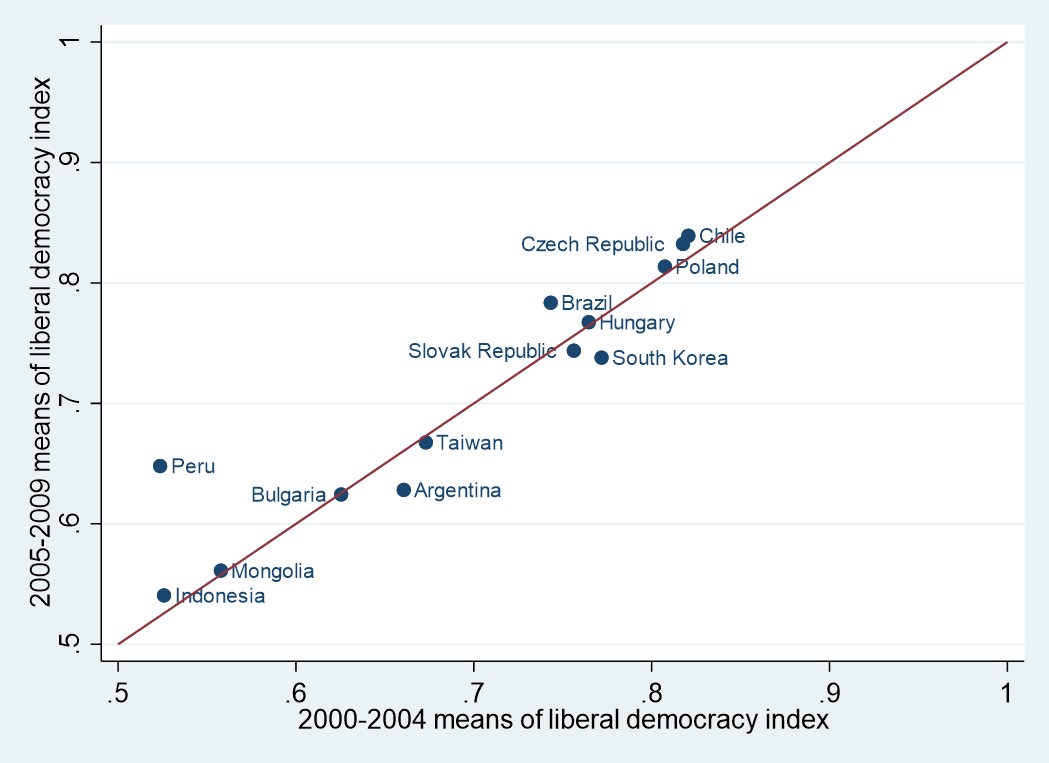

Figure 4. Liberal Democracy Index Scores of 18 Third-wave Democratizers, 2000-2004 versus 2005-2009

Source: V-Dem (https://www.v-dem.net/data/)

Note: Colombia, Mexico, Philippines, Romania, and Thailand are excluded due to their lower scores.

Figure 4 shows a scatterplot in which the horizontal axis represents the 2000-2004 mean values of liberal democracy index scores of the eighteen third-wave democratizers, and the vertical axis indicates the 2005-2009 mean values of liberal democracy index scores of the eighteen third-wave democratizers. If a country is on the left side of the 45-degree line, its quality of democracy is improved. If a country is on the right side of the 45-degree line, its quality of democracy deteriorates. Among the higher horizontal accountability performers, Chile and Peru improve their quality of democracy. Among the lower horizontal accountability performers, South Korea and Argentina worsen their quality of democracy. In terms of democracy, South Korea seems to be one of the horizontal-accountability-triggered democratic backsliding cases among the eighteen third-wave democratizers during the period (Sato et al. 2022).

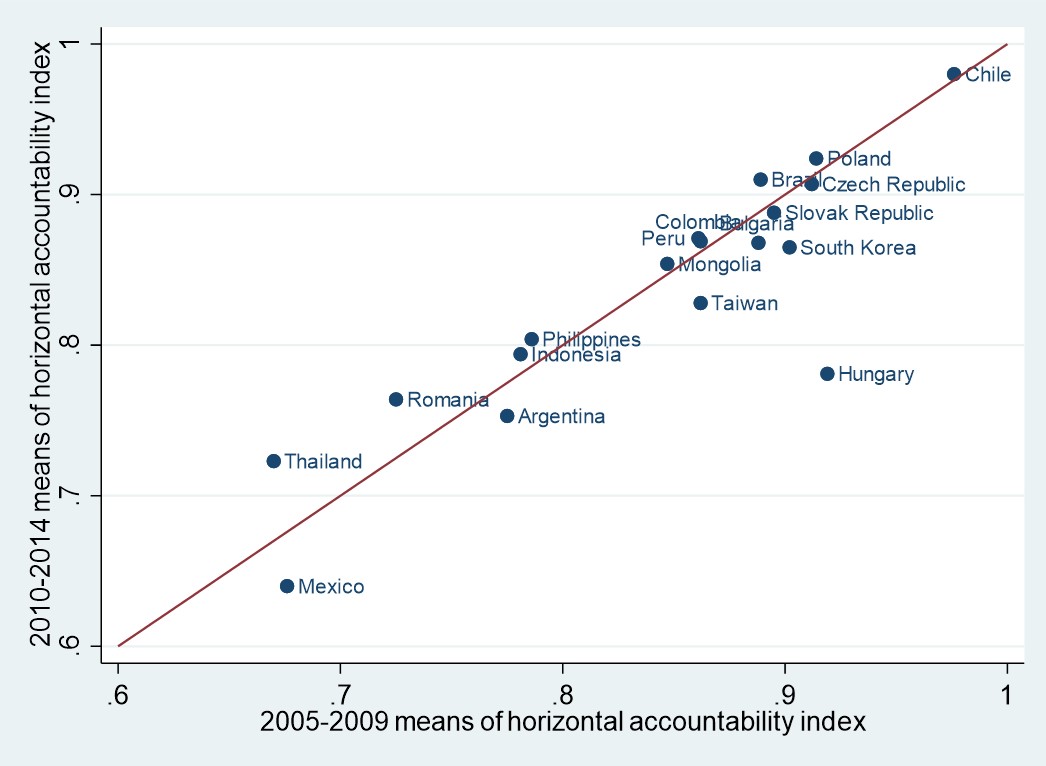

Figure 5. Horizontal Accountability Index Scores of 18 Third-wave Democratizers, 2005-2009 versus 2010-2014

Source: V-Dem (https://www.v-dem.net/data/)

Figure 5 illustrates a scatterplot in which the horizontal axis shows the 2005-2009 mean values of the horizontal accountability index scores of the eighteen third-wave democratizers, and the vertical axis represents the 2010-2014 mean values of the horizontal accountability index scores of the eighteen third-wave democratizers. If a country is on the left side of the 45-degree line, its de facto horizontal accountability is improved. If a country is on the right side of the 45-degree line, its de facto horizontal accountability deteriorates. Brazil, Romania, and Thailand represent the former, whereas South Korea, Taiwan, Argentina, Hungary, and Mexico typify the latter. Regarding de facto accountability, South Korea seems to be one of the continuous horizontal accountability erosion cases among the eighteen third-wave democratizers during the period.

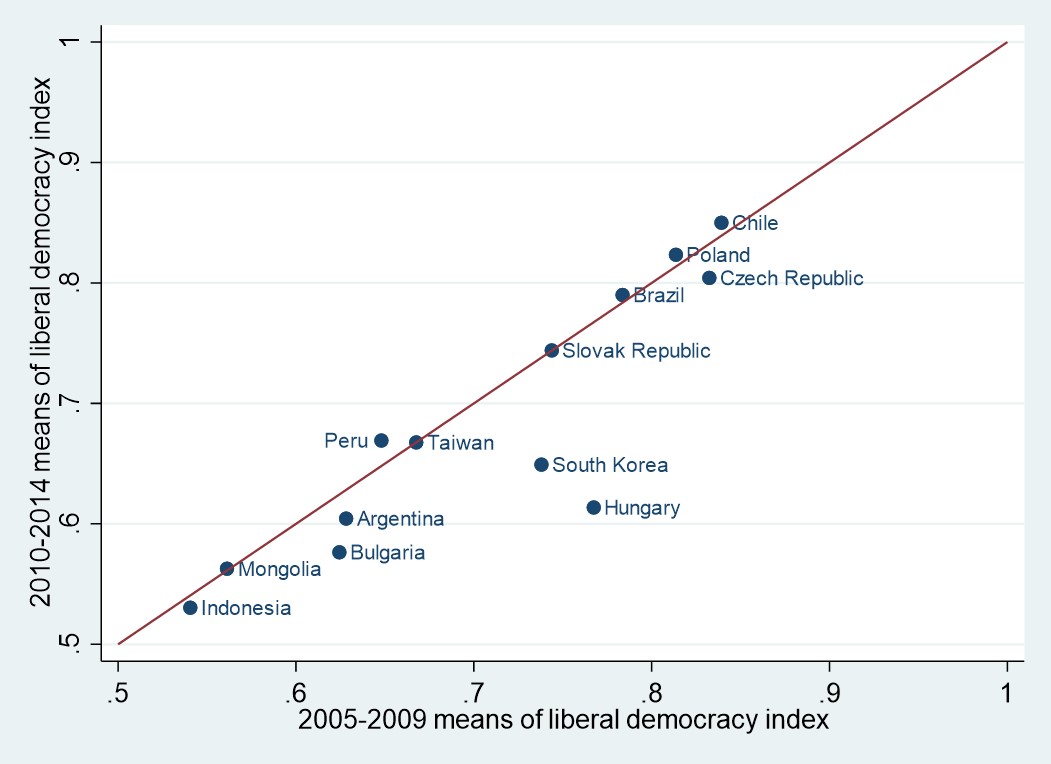

Figure 6. Liberal Democracy Index Scores of 18 Third-wave Democratizers, 2005-2009 versus 2010-2014

Source: V-Dem (https://www.v-dem.net/data/)

Note: Colombia, Mexico, Philippines, Romania, and Thailand are excluded due to their lower scores.

Figure 6 shows a scatterplot in which the horizontal axis represents the 2005-2009 mean values of liberal democracy index scores of the eighteen third-wave democratizers, and the vertical axis indicates the 2010-2014 mean values of liberal democracy index scores of the eighteen third-wave democratizers. If a country is on the left side of the 45-degree line, its quality of democracy is improved. If a country is on the right side of the 45-degree line, its quality of democracy deteriorates. Among the lower horizontal accountability performers, South Korea, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Argentina, and Bulgaria worsen their quality of democracy. In terms of democracy, South Korea seems to be one of the horizontal accountability-accelerated democratic backsliding cases among the eighteen third-wave democratizers during the period (Shin 2021).

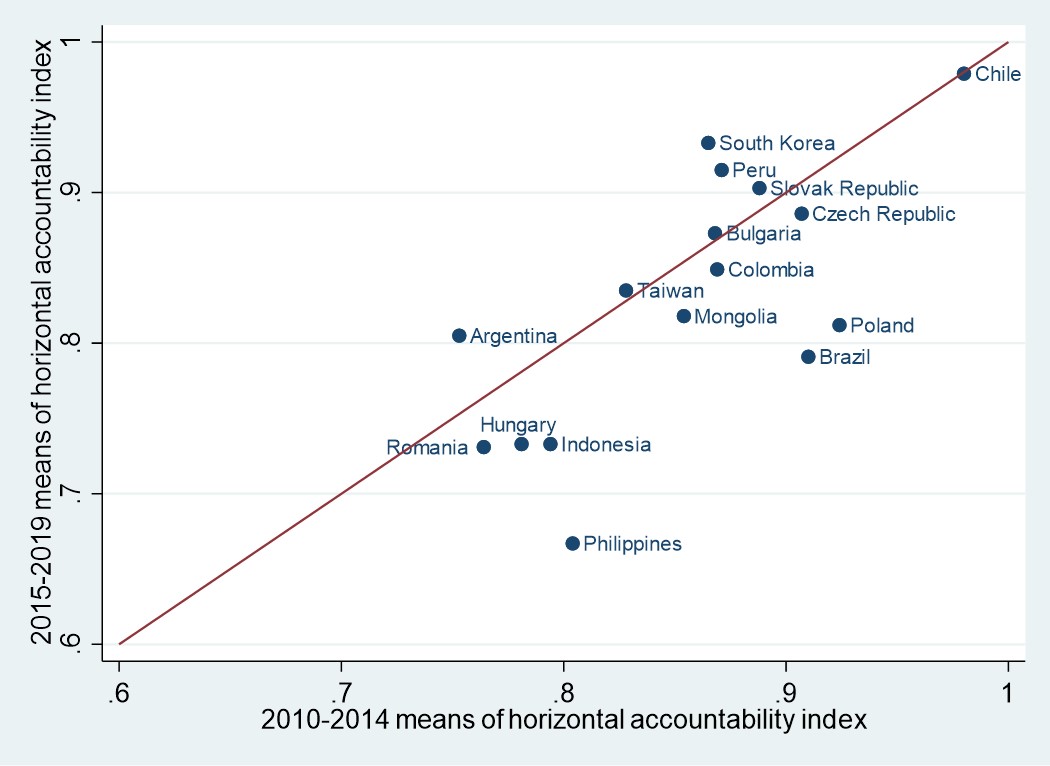

Figure 7. Horizontal Accountability Index Scores of 18 Third-wave Democratizers, 2010-2014 versus 2015-2019

Source: V-Dem (https://www.v-dem.net/data/)

Figure 7 illustrates a scatterplot in which the horizontal axis shows the 2010-2014 mean values of the horizontal accountability index scores of the eighteen third-wave democratizers, and the vertical axis represents the 2015-2019 mean values of horizontal accountability index scores of the eighteen third-wave democratizers. If a country is on the left side of the 45-degree line, its de facto horizontal accountability is improved. If a country is located on the right side of the 45-degree line, its de facto horizontal accountability deteriorates. South Korea, Peru, and Argentina represent the former, whereas Poland, Brazil, Indonesia, Hungary, and the Philippines typify the latter. Regarding de facto accountability, South Korea seems to be one of the horizontal accountability-erosion-reversal cases among the eighteen third-wave democratizers during the period.

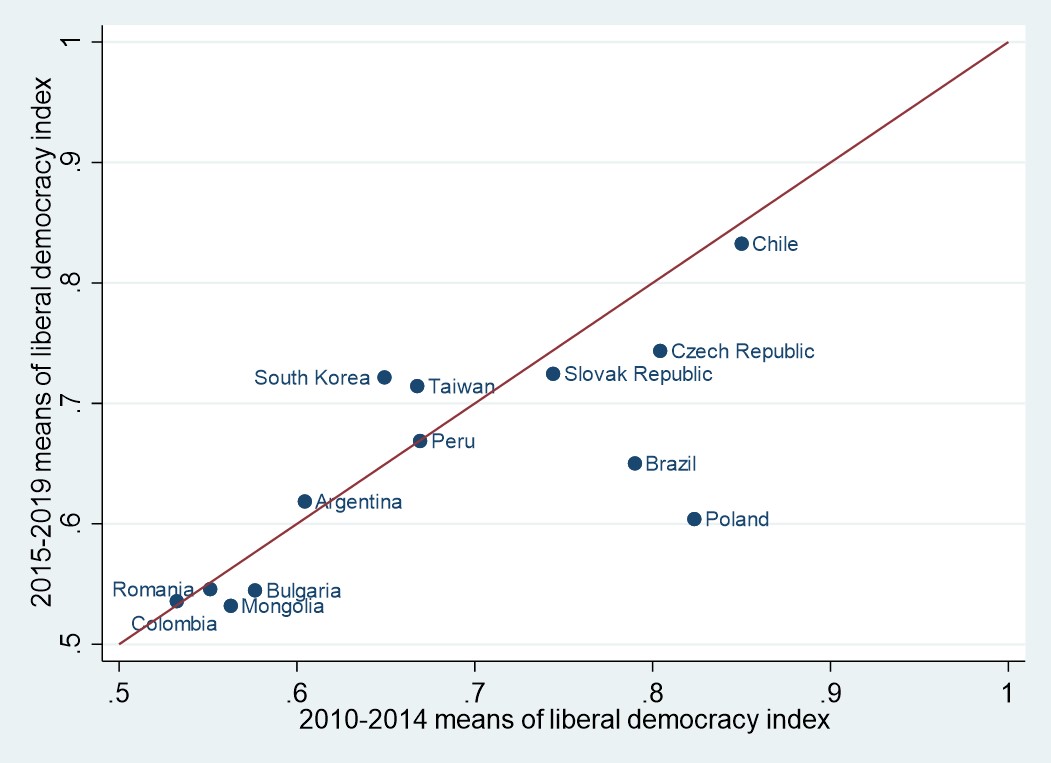

Figure 8. Liberal Democracy Index Scores of 18 Third-wave Democratizers, 2010-2014 versus 2015-2019

Source: V-Dem (https://www.v-dem.net/data/)

Note: Mexico, the Philippines, and Thailand are excluded due to their lower scores.

Figure 8 shows a scatterplot in which the horizontal axis represents the 2010-2014 mean values of liberal democracy index scores of the eighteen third-wave democratizers, and the vertical axis indicates the 2015-2019 mean values of liberal democracy index scores of the eighteen third-wave democratizers. Countries located on the left side of the 45-degree line indicate an improved quality of democracy, while countries on the right side of the 45-degree line indicate a deteriorated quality of democracy. Among the higher horizontal accountability performers, South Korea has an improved quality of democracy. Among the lower horizontal accountability performers, Poland and Brazil have a decreased quality of democracy. In terms of democracy overall, South Korea seems to be one of the horizontal accountability-recovered democratic resilience cases among the eighteen third-wave democratizers during the period (Laebens and Luhrmann 2021).

4. Conclusion

This study shows that workable de jure horizontal accountability mechanisms are entrenched in South Korea’s constitutional design in which inter-branch checks and balances provisions distribute relatively equal powers among the executive, legislature, and judiciary. On parchment, South Korea’s polity appears to escape the institutional trap in which the imperial president meets a recalcitrant assembly that imperils horizontal accountability and democracy.

Concerning de facto horizontal accountability, performance seems to betray the institutional optimality of de jure horizontal accountability mechanisms in South Korea. As South Korea’s de facto accountability performance has oscillated between deterioration and restoration, so has the democratic quality of the country. The finding of a significant hiatus between de jure accountability and de facto accountability and de facto accountability performance correlates with the quality of democracy necessitates further research on why there is a gap between formal accountability institutions and actual accountability outcomes and how it affects democracy in South Korea. ■

References

Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Adam Glynn, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Daniel Pemstein, Brigitte Seim, Svend-Erik Skaaning, and Jan Teorell. 2020. Varieties of Democracy: Measuring Two Centuries of Political Change. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Elkins, Zachary, Tom Ginsburg, James Melton. 2023. “Constitute: The World’s Constitutions to Read, Search, and Compare.” https://www.constituteproject.org/content/indices_data?lang=en

Fish, M. Steven and Matthew Kroenig. 2009. The Handbook of National Legislature: A Global Survey. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Laebens, Melis G. and Anna Luhrmann. 2021. “What Halts Democratic Erosion? The Changing Role of Accountability.” Democratization 28, 5: 908-928.

Luhrmann, Anna, Kyle L. Marquardt, and Valeriya Mechkova. 2020. “Constraining Governments: New Indices of Vertical, Horizontal, and Diagonal Accountability.” American Political Science Review 114, 3: 811-820.

Sato, Yuko, Martin Lundstedt, Kelly Morrison, Vanessa A. Boese, Staffan I. Lindberg. 2022. “Institutional Order in Episodes of Autocratization.” V-Dem Working Paper.

Shin, Doh Chull. 2021. “Democratic Deconsolidation in East Asia: Exploring Systеm Realignments in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan.” Democratization 28, 1: 142-160.

[1] Article 52: Bills may be introduced by members of the National Assembly or by the Executive.

[2] Article 75: The President may issue presidential decrees concerning matters delegated to him by law with the scope specifically defined and also matters necessary to enforce laws.

[3] Article 128: A proposal to amend the Constitution shall be introduced either by a majority of the total members of the National Assembly or by the President.

[4] Article 76: (1) In time of internal turmoil, external menace, natural calamity or a grave financial or economic crisis, the President may take in respect to them the minimum necessary financial and economic actions or issue orders having the effect of law, only when it is required to take urgent measures for the maintenance of national security or public peace and order, and there is no time to await the convocation of the National Assembly; (2) In case of major hostilities affecting national security, the President may issue orders having the effect of law, only when it is required to preserve the integrity of the nation, and it is impossible to convene the National Assembly.

[5] Article 53: (1) Each bill passed by the National Assembly shall be sent to the Executive, and the President shall promulgate it within fifteen days; (2) In case of objection to the bill, the President may, within the period referred to in Paragraph (1), return it to the National Assembly with written explanation of his objection, and request it be reconsidered. The President may do the same during adjournment of the National Assembly.

[6] Article 43: Members of the National Assembly shall not concurrently hold any other office prescribed by law; National Assembly Act Article 29: (1) No National Assembly member shall concurrently hold office, except the office of Prime Minister or a member of the State Council.

[7] Article 62: (2) When requested by the National Assembly or its committees, the Prime Minister, members of the State Council or government delegates shall attend any meeting of the National Assembly and answer questions.

[8] Article 61: (1) The National Assembly may inspect affairs of state or investigate specific matters of state affairs, and may demand the production of documents directly related thereto, the appearance of a witness in person and the furnishing of testimony or statements of opinion.

[9] Article 76: (3) In case actions are taken or orders are issued under Paragraphs (1) and (2), the President shall promptly notify the National Assembly and obtain its approval.

[10] Article 41: (1) The National Assembly shall be composed of members elected by universal, equal, direct and secret ballot by the citizens.

[11] Article 60: (2) The National Assembly shall also have the right to consent to the declaration of war, the dispatch of armed forces to foreign states, or the stationing of alien forces in the territory of the Republic of Korea.

[12] Article 60: (1) The National Assembly shall have the right to consent to the conclusion and ratification of treaties pertaining to mutual assistance or mutual security; treaties concerning important international organizations; treaties of friendship, trade and navigation; treaties pertaining to any restriction in sovereignty; peace treaties; treaties which will burden the State or people with an important financial obligation; or treaties related to legislative matters.

[13] Article 104: (1) The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court shall be appointed by the President with the consent of the National Assembly; (2) The Supreme Court Justices shall be appointed by the President on the recommendation of the Chief Justice and with the consent of the National Assembly.

[14] Article 47: (1) A regular session of the National Assembly shall be convened once every year as prescribed by law, and extraordinary sessions of the National Assembly shall be convened upon the request of the President or one fourth or more of the total members.

[15] Article 103: Judges shall rule independently according to their conscience and in conformity with the Constitution and law.

[16] Article 104: (1) The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court shall be appointed by the President with the consent of the National Assembly; (2) The Supreme Court Justices shall be appointed by the President on the recommendation of the Chief Justice and with the consent of the National Assembly.

[17] Article 106: (1) No judge shall be removed from office except by impeachment or a sentence of imprisonment or heavier punishment, nor shall he be suspended from office, have his salary reduced or suffer any other unfavorable treatment except by disciplinary action.

[18] Article 111: (1) The Constitution Court shall adjudicate the following matters: 1. The constitutionality of a law upon the request of the courts.

[19] Article 111: (1) The Constitution Court shall adjudicate the following matters: 3. Dissolution of a political party.

[20] Article 111: (1) The Constitution Court shall adjudicate the following matters: 2. Impeachment.

[21] Parentheses indicate the year in which the country makes the democratic transition from closed or electoral autocracy to electoral or liberal democracy pursuant to Regimes of the World dataset of Varieties of Democracy project (https://v-dem.net/data/). In each region, the six largest third-wave democratizers in terms of population in 1990 were selected.

■ Jung Kim is an associate professor of political science and dean of academic affairs at University of North Korean Studies (UNKS). Currently, he is a visiting professor at Graduate School of International Studies and Underwood International College of Yonsei University, a regional coordinator of Asia Democracy Research Network, an editorial committee member of Asian Perspective and Tamkang Journal of International Affairs, a columnist for Seoul Shinmun, and a policy advisory committee member of Republic of Korea’s Defense Intelligence Agency. He earned his undergraduate degree in political science from Korea University and graduated from Yale University with his doctoral degree in political science.

■ 담당 및 편집: 박한수_EAI 연구원

문의: 02-2277-1683 (ext. 204) hspark@eai.or.kr