![[Disinformation and Democracy Series] Populism, Disinformation, and South Korean Democracy](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/20240613162941231430013.jpg)

[Disinformation and Democracy Series] Populism, Disinformation, and South Korean Democracy

| Working Paper | 2024-06-13

Won-Taek Kang

Chair, EAI Democracy Research Center

Professor, Seoul National University

Won-Taek Kang, Chair of the EAI Democracy Research Center, observes that political polarization and populist politics create favorable conditions for the production, distribution, and consumption of fake news. Based on the results of EAI`s public opinion survey, Kang analyzes that a decline in trust in political institutions and the judiciary increases susceptibility to disinformation. He emphasizes the urgent need for reforms towards more competitive and transparent politics.

1. Introduction

While the “third wave” of democratization, starting in the mid-1970s, initially sparked optimism about liberal democracy, recent trends have raised concerns about democratic backsliding. This phenomenon is evident not just in emerging democracies, but also in long-established Western democracies like the United States and the United Kingdom. Notably, the rise of populism has become a significant factor in the erosion of democracy. The election of former President Donald Trump in 2016 and the Brexit referendum are key examples, demonstrating that even countries with a robust democratic tradition are not immune to the impacts of populism.

Populism in South Korea has garnered comparatively less attention than in Western democracies, possibly because it has not witnessed a populist party's overwhelming victory in congressional elections, as seen in Europe, or the rise of a populist presidential figure akin to Donald Trump. In South Korean politics, populism has often been used as a derogatory term or employed to criticize the irresponsible election pledges of political adversaries.

Recent political situations in South Korea are fostering an environment conducive to the rise of populism (Kang 2021). Primarily, there is a prevalent lack of trust in domestic politics, accompanied by a significant number of citizens who do not support any specific political party. This detachment is largely due to their dissatisfaction with the current state of polarized politics. Additionally, confidence in political institutions like the National Assembly, the judiciary, and administrative agencies is low, accompanied by an anti-elite sentiment. Consequently, South Koreans are increasingly looking towards "outsiders" with no political background as potential solutions to their discontent in presidential elections.

While labeling South Korean politics as "populist" in the same vein as some Western democracies might be misleading, it has undeniably become highly "vulnerable" to populist politics. This vulnerability stems from widespread distrust in politics, skepticism towards the National Assembly and political parties, anti-elitism, and deep political polarization. Such a climate becomes favorable for the production, distribution, and consumption of disinformation.

This paper highlights the importance of considering not only the political suppliers, such as individual politicians or parties, in analyzing populism and polarization, but also the attitude of the political consumers who are willing to accept disinformation. In other words, populism should not be solely attributed to politicians or parties propagating populist rhetoric or agendas, but also to the general populace that readily embraces these messages. The paper argues that populism thrives in an environment of political polarization, and that the receptivity to and consumption of disinformation are intertwined with a populist mindset.

2. Populism

Defining "populism" is a complex task, despite the frequent use of term in political discourse (Kang 2021). Often described as a “thin-centered ideology” due to its lack of a singular, clear definition (Mudde 2004; Stanley 2008), populism's general characteristics in practical politics can be outlined as follows.

First, as the term suggests, populism is inherently linked to the “people.” The phrase that characterizes populism as “a shadow cast by democracy itself” (Canova 1999: 2-3) indicates the difficulty of separating the democratic systern from populism at its core. Here, the adversary of the “people” is the elites. Populism is framed as a form of politics where the “pure people” stand against the “corrupt elite,” ultimately leading to the triumph of the people's volonté générale (general will) (Mudde 2004; Mudde and Kaltwasser 2017). In sum, populism fundamentally embodies anti-elitist qualities. When elements like corruption are coupled with popular discontent over elite politicians' failure to effectively address issues like unemployment or growing economic polarization, it fosters an environment highly conducive to the rise of populism.

The second characteristic of populism is its distrust towards representative democracy. Populist supporters often view political parties and elites as merely representing vested interests. Consequently, they favor direct political participation and expression of the masses' will, bypassing traditional party or interest group channels. This perspective advocates for the people's right to decide on key policies through direct means such as popular votes, circumventing the need for elite involvement (Suh 2008: 117). In essence, populism reflects skepticism towards party politics, which, in principle, is the cornerstone of liberal democracy.

The third trait of populism is its politics of division and exclusion, sharply delineating "allies" and "enemies." In recent populist trends, the definition of "us" is often narrowly based on cultural factors such as religion, race, social hierarchy, and tradition, fostering hostility and exclusion towards "them" (Galston 2019:11). This is evident in anti-immigration, anti-refugee sentiment, chauvinism, protectionism, separatism, anti-EU attitudes, and the surge in nationalism, racism, patriotism, and regionalism seen in Europe. Another example is Trump's 2016 presidential campaign proposal to build a "big beautiful wall" along the Mexican border. Populists typically assign blame and responsibility for social issues to external "enemies," offering seemingly straightforward solutions (Mounk 2018: 15). In fact, the United States and Europe are witnessing a trend of attributing socioeconomic challenges and conflicts to immigrants or minorities, laying the groundwork for populism to thrive.

The fourth element is its anti-liberal, and collectivist inclination. The fundamental issue with populism is its rejection of pluralism, a core value of liberal democracy. Pluralism advocates a concept of "fair terms of living together as free, equal, … [and] irreducibly diverse citizens" (Galston 2019: 12-13), which is inherently incompatible with the populist ethos that prioritizes purity and superiority of certain groups and emphasizes the will of the people. Therefore, populism, oriented around the popular will, struggles to coexist with pluralism, which accepts and respects differences.

The fifth aspect of populism is its focus on the “heartland,” which symbolizes the “idealized conception of the community they serve” (Taggart 2017: 163-169). The heartland, in essence, is an imagined landscape that reflects a time of perceived struggle that necessitates such idealized notions. This ideal society is not a utopia but rather a vision constructed from nostalgic recollections of the past, aimed at reclaiming what is believed to have been lost. A notable example of this is Trump’s 2016 campaign slogan, “Make America Great Again.”

The sixth feature of populism is its preference for a charismatic leader. The influential and charismatic figure is not only seen as an embodiment of the values people desire in their leaders, but is also perceived as possessing special abilities to protect and rescue the populace in times of crisis (Joo 2016: 59-61). This tendency frequently leads to the rise of illiberal or delegative democracy.

Considering these characteristics, populism can be characterized as a form of reactionary politics that, either explicitly or subconsciously, yearns for an ideological heartland. This inclination is a response to perceived societal risks and a critique of the ideas, institutions, and practices associated with representative politics (Taggart 2017: 23).

Populism is increasingly evident in South Korea, although categorizing it definitively as either populist or simply popular is challenging. The discourse around populism began during the Roh Moo-hyun administration and gained significant prominence in the Moon Jae-in administration. The Moon administration's call for “Drain the Swamp (jeok-pye-cheong-san: 적폐청산)” in the wake of former President Park Geun-hye's impeachment is a clear indicator of this tendency (Cha 2021: 152-153). Additionally, the use of terms like “Natural Grown Japanese (to-chag-wae-gu: 토착왜구)” by the pro-Moon faction reflects their efforts to construct an image of an enemy, highlighting the populist leanings in recent South Korean politics.

The term "Natural Grown Japanese," embodying a blend of populism and anti-Japanese nationalism, or a mix of racism and anti-elitism, reflects a populist mindset that adopts exclusionary, chauvinistic language. This concept marginalizes adversaries while denying pluralism. It has been particularly prominent against the backdrop of diplomatic tensions between South Korea and Japan following the appellate court's decision on wartime sexual slavery compensation, as well as the “Yoon Mee-hyang Case.” Conversely, at the other extreme of identity politics or tribalism, there exists a process that assumes the moral superiority of the group opposing what is perceived as a great evil. (Cha 2021: 153) (Translated)

Furthermore, by actively promoting and utilizing mechanisms like the Blue House national petition (cheong-wa-dae gug-min-cheong-won: 청와대 국민청원) and “candlelight protests,” the Moon Jae-in administration demonstrated a preference for direct democracy over representative democracy, while sidelining traditional party discussions or National Assembly deliberations.

[The Moon Jae-in administration] shows a preference for engaging with amorphous movements like mass protests and national petitions over traditional parliamentary or party politics and interest management by structured organizations like labor unions or functional groups. This approach amplifies a sense of political urgency, often exerting pressure through biases and negative emotions such as prejudice, hatred, and animosity. In this context, representative democracy, characterized by respect for diverse opinions and reliant on compromise and mediation, is perceived merely as a tool to uphold existing power structures. The values essential in a pluralistic society, such as respect for imperfections and a cautious tolerance for differences, are dismissed as weakness or lack of conviction. Contrary to historical efforts to build community and reduce conflict through institutionalized trust, this stance leans more towards fostering distrust, favoring conspiracy theories, and showing a tendency to dominate others' thoughts. (Park 2020: 18) (Translated)

The populist narrative of "we are good and they are evil," combined with the political dynamics outlined above, has significantly contributed to the acceleration of political polarization. Additionally, digitization has led to a weakening of traditional media's gatekeeping role. The rise of new media platforms like YouTube and various social media has created an environment that not only exacerbates polarization but also facilitates the spread and consumption of disinformation. In such a highly polarized context, communication among people who share similar views has intensified, effectively creating “echo chambers” that reinforce and amplify existing opinions (Diaz Ruiz and Nilsson 2023).

This environment leads to biased information consumption, where individuals selectively accept what aligns with their preferences or what they perceive as favorable. Such conditions are ripe for the production, dissemination, and consumption of disinformation. Numerous factors contribute to the receptivity to fake news, but populist politics play a significant role. The differentiation between "us" and "them" in a polarized setting, and the resultant division framed as a contest between good and evil, significantly amplify the susceptibility to disinformation.

The subsequent section draws upon empirical data to analyze influence of partisan division, as well as the attitude towards populism, on the receptivity to disinformation.

3. Populism, Political Partisanship, and Disinformation

3.1 Partisan Polarization

As previously demonstrated, populism in South Korea is closely intertwined with partisan polarization. The key issue here is that populism and polarization are not merely problems of political suppliers, such as politicians or parties, but are also related to the attitudes of political consumers, namely, the general citizens. Populism inherently splits society into blocs of “us” versus “them.”

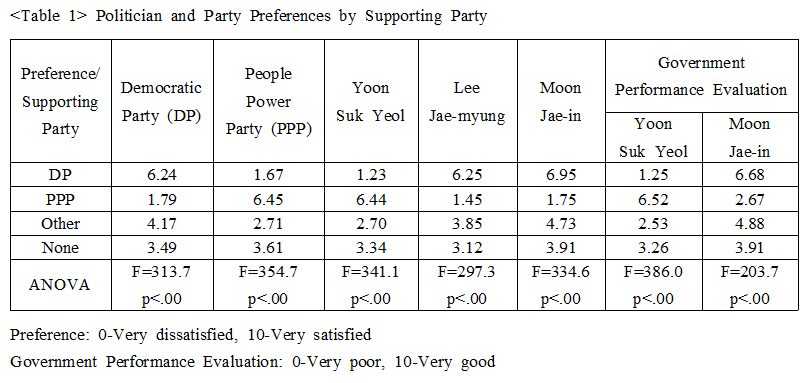

Understanding the extent of political polarization in the South Korean society is essential. To this end, this research initially investigated the differences in partisan preferences. Table 1 analyzed the preferences towards the two major parties and key political leaders, as well as the government performance evaluation, categorized by the respondents’ political affiliation.

As shown in Table 1, party preferences significantly vary depending on the supporting party. Notably, the preferences of Democratic Party (DP) and People Power Party (PPP) supporters are diametrically opposed. Supporters of both DP and PPP rated members of their respective parties highly, with an average score of 6, but allocated less than 2 points to members of the rival party. Meanwhile, individuals without a specific party identification demonstrated a neutral stance, giving consistent scores ranging from 3 to 4 points to all parties. Table 1 clearly illustrates that one's allegiance to a particular party profoundly influences their perception of opposing parties or politicians. This variation in mean scores across different groups is statistically significant in all sections of the study.

The subjective perception of ideological distance was examined, focusing on how respondents view the ideological differences between two opposing parties based on their allegiance. It specifically investigated the perceived ideological positions of the DP and PPP along the ideological spectrum, as believed by their supporters, akin to the depiction in Picture 1.

The findings reveal a clear pattern of ideological proximity tied to party support, corroborating the proximity model proposed by Downs (1957). DP supporters perceived the ideological distance between themselves and the DP as 0.28, compared to a distance of 3.85 from the PPP. Similarly, the perceived distance between DP supporters and Lee Jae-Myung (the DP leader) was 0.58, while it was 3.96 with President Yoon. This pattern was mirrored among PPP supporters, who perceived their ideological distance from the PPP as 0.74, and from President Yoon as 0.99. Conversely, their perceived distance from the DP was 3.84, and from Lee Jae-Myung as 4.07.

Moreover, both groups of supporters perceived a substantial ideological distance between the two rival parties and their leaders. DP supporters believed the ideological gap between the DP and PPP was 4.13, and between Lee Jae-Myung and President Yoon, it was 4.54. PPP supporters perceived these distances as even greater, with a 4.58 gap between the two parties and a 5.06 gap between Lee Jae-Myung and President Yoon. These findings suggest that party affiliation significantly influences the perception of ideological distances among supporters.

This indicates that Korean voters perceive a significant ideological divide between political parties. Such a perception of the parties being “ideologically distant” may be a key factor complicating efforts to mitigate polarization.

Moreover, both DP and PPP supporters perceived their own party as more ideologically moderate, while viewing the rival party as extreme. DP supporters rated the DP and Lee Jae-Myung between 3 and 4 on the ideological scale, indicating a relatively moderate progressive stance, whereas they saw the PPP or President Yoon as being at an 8, representing a very strong conservative position. Similarly, PPP supporters placed their own alignment at 6 to 7, suggesting a moderately conservative viewpoint, while they considered the DP to be at a 2 to 3, indicative of a highly progressive stance. In other words, this shows that political polarization arises from the belief that one's own supported party is moderate, while the rival party is perceived as too extreme. Consequently, in times of political deadlock or stagnation, there tends to be a propensity to assign blame to the “other side” rather than to one's own.

The analysis shown in Picture 1 draws on each respondent's self-identification on the ideological spectrum. Critics often point out that this subjective approach to measuring ideology can be problematic, as individuals might use varying standards for evaluation, potentially affecting the precision of the assessment (Park, Han, and Lee 2021: 131-133). To address these concerns, this study further investigates the disparities in opinions regarding specific policy positions among respondents, categorized by the political parties they support.

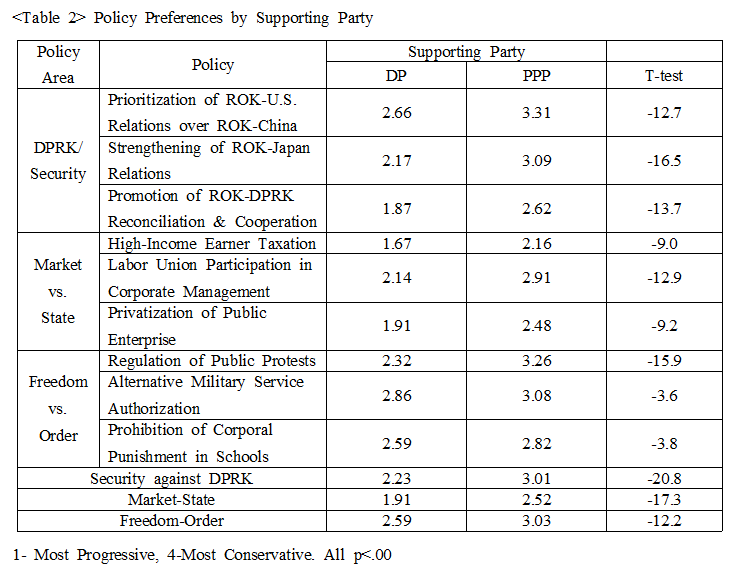

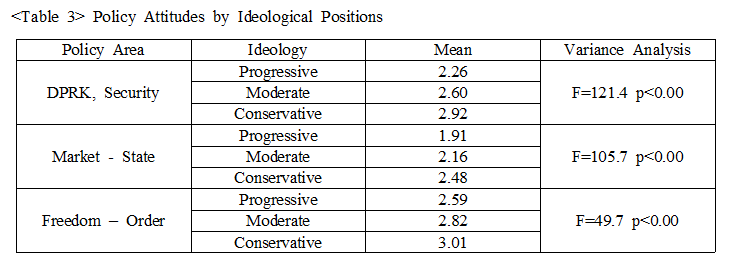

Table 2 presents nine policy-related questions, categorized into three ideological realms as identified by Kang (2005). The first category focuses on North Korea and security-related policies, reflecting intense post-2002 ideological conflicts in diplomacy and security. Table 3 explores attitudes towards strengthening relations with the U.S. and Japan, and cooperation with DPRK. The second category delves into economic policies, the classical ideological divide between market competition and efficiency (right-wing) versus state intervention and equality (left-wing). It includes questions on taxation, labor union management participation, and public enterprise privatization. The third category addresses social issues, highlighting differences in libertarian versus authoritarian attitudes. Progressive views are linked to individual freedom and choice, while conservative ones emphasize order, tradition, and authority. This section includes policies on protest regulations, substitute military service, and physical punishment in schools.

The findings revealed a remarkable consistency in the differing viewpoints of supporters of DP and PPP across all nine policy areas, spanning North Korea and security, economic, and social categories. This indicates that partisan stances significantly influence opinions across all policy sectors. Table 2 clearly proves that partisan polarization in Korean society today is exceptionally profound.

While one could attribute polarization to these differing policy attitudes, it is unclear if such stances truly reflect the shared attitudes of each party's supporters. These differences might result from persuasion, where supporters align with their party's stance, or from projection, where individuals assume the policy direction of the party they support (Brody and Page 1972). Essentially, this could be a rationalization of one's own policy attitude to align with their affiliated party.

A clearer picture emerges when these attitudes are examined in relation to ideological stances. As shown in Table 3, there is a distinct difference in the three policy areas based on conservative, progressive, and moderate ideological positions. The pattern of mean values is in the order of progressive < moderate < conservative. This observation suggests a strong correlation between party support and individual ideological leanings shown in Table 2.

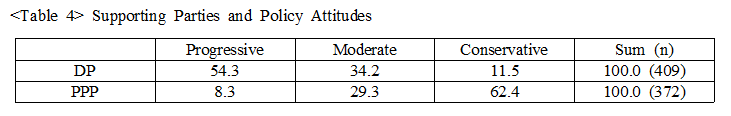

However, Table 4 presents a different scenario where party support and ideological attitude are not always aligned. For example, among Democratic Party supporters, 54.3% identified as progressive, but a significant 34.2% saw themselves as moderate, and 11.5% as conservative. Similarly, in the People Power Party, while 62.4% of supporters identified as conservative, 30% considered themselves moderate, and 8.3% progressive. This indicates that while there is some correlation between partisanship and ideology, it is not accurate to assume they always coincide.

Therefore, the consistent and pronounced partisan division observed in Table 2 should be considered more a result of persuasion or projection influenced by the parties people support, rather than a direct reflection of their ideological stances. The differences are likely to have been amplified by the involvement of party affiliations, rather than representing genuine distinctions in the policy positions held by ordinary citizens.

3.2 Partisan Polarization and Populism

This paper now examines the impact of partisan polarization on populism. To analyze this, the study utilized populism-related survey questions developed by Akkerman et al. (2014).

|

1. The politicians in the parliament need to follow the will of the people. 2. The people, and not the politicians, should make our most important policy decisions. 3. I would rather be represented by a citizen than by a specialized politician. 4. The political differences between the elite and the people are larger than the differences among the people. 5. Politicians compromise to protect their interests and privileges. 6. Elected officials talk too much and take too little action. 7. Politics is ultimately a struggle between good and evil. 8. What people call “compromise” in politics is really just selling out on one’s principles. |

The eight questions can be categorized into three aspects of populism. The first three questions reflect skepticism toward representative systern and preference for direct democracy or citizen participation. Questions 4 through 6 showcase an anti-elite sentiment, and the remaining two highlight anti-pluralism, highlighting a confrontational dichotomy between “us” and “them.”

The average responses to the eight items were as follows:

The statement “Elected officials talk too much and take too little action” received the highest average score (4.21), closely followed by “Politicians compromise to protect their interests and privileges” (4.14). These indicate a significant level of distrust and anti-elitism. Subsequent responses “The politicians in the parliament need to follow the will of the people” (4.11) and “The people, and not the politicians, should make our most important policy decisions” (3.96) underscore a strong preference for public self-leadership over a representative systern. Overall, the sum of these aspects ranked in the order of anti-elitism > public self-leadership > politics of good versus evil.

The analysis focused on the relationship between populist attitudes and political party support. Table 6 indicates that individuals who support a specific party are more inclined towards populism, suggesting a connection with established parties. This finding contrasts with the trend in Europe, where populism is often driven by emerging, non-mainstream parties. Interestingly, no significant statistical difference was found in anti-elitism attitudes, implying that this sentiment is prevalent regardless of party support, and it had the highest mean score among the categories assessed.

Further examination involved the DP and PPP supporters' attitudes towards populism. According to Table 7, a distinction in populist attitudes was observed based on party support, with DP supporters exhibiting a higher propensity for populist sentiments, especially in terms of public self-leadership and anti-elitism. However, there was no significant difference between the two parties concerning the populist attitudes associated with the good vs. evil dichotomy and the politics of confrontation.

Based on these findings, the research sought to identify the factors that influence populist attitudes, considering various independent variables such as partisan support, attitudes towards political leadership, ideological leanings, political satisfaction, institutional trust, political knowledge, interest, age, education level, and other socioeconomic factors. The linear regression analysis results is presented in Table 8.

For the public self-leadership category, a stronger populist attitude was observed in individuals who lacked party support, held progressive ideologies, and exhibited a high level of political interest. Socioeconomic factors also played a role, with older males showing stronger populist tendencies. In contrast, anti-elitist attitudes were more pronounced in individuals who held lower trust in President Yoon and showed a greater preference for his predecessor. This aligns with the patterns observed in Table 6, where these attitudes were notably prevalent among certain supporters.

In the politics of good vs. evil category, the analysis found that a stronger populist attitude was associated with individuals who supported a political party, had a higher level of trust in the President, and leaned towards conservative ideologies. Table 7, despite showing statistically insignificant results, adds credibility to this finding in that this attitude was somewhat more prevalent among PPP supporters. The analysis also revealed that a greater difference in preference between the two major parties correlated with a higher receptivity to confrontational politics. Furthermore, this receptivity was increased among individuals with lower political knowledge or education levels, and among older demographics.

Mass leadership, which suggests a rejection of the representative systern, tended to be more appealing to individuals who do not align with any political party. Conversely, the perception of politics as a battle between good and evil—a mindset fostering confrontation—showed a higher prevalence among those who do align with a party. In essence, viewing politics through a lens of good versus evil is influenced by partisanship, which, in turn, contributes to the shaping of populist sentiments. Table 8 further corroborates the notion that populist attitudes are also linked to party support.

Table 8 notably highlights that trust in political institutions significantly influences populism. Statements like “Public officials do not listen to concerns of the general public” and a general distrust towards the National Assembly were statistically significant across three populism categories and the aggregate of all eight questions. Additionally, the statement “People like me speaking out about the government's actions is pointless” showed significance in two categories. Age was a factor, with older individuals showing higher receptivity to populism, indicating that disillusionment and dissatisfaction with political responsiveness—or the belief that political institutions fail to address citizens' needs and voices—fuel populist sentiment. Essentially, the potency of populist appeal is closely tied to distrust in representative bodies like the National Assembly and a sense of political alienation, where individuals feel their concerns and demands are ignored by the government or public official.

3.3 Populism and disinformation

Building on this analysis, the paper explores the factors influencing individuals' attitudes towards disinformation. Participants in the survey were presented with eight instances of fabricated news and asked to rate their likelihood of believing each piece using a Likert Scale. The scale ranged from '1 - Very Unlikely' to '4 - Very Likely.' Among the eight fake news items, four were designed to appeal to supporters of the Democratic Party, while the other four were targeted at backers of the People Power Party.

|

○ Fake news appealing to Democratic Party supporters - The relocation of the Office of the President to Yongsan has led to an increased traffic congestion in the area. - Yoon administration is allegedly not being transparent about the Fukushima Daiichi treated water discharge issue. - Han Dong-hoon (former Justice Minister) reportedly engaged in a late-night drinking party with President Yoon and 30 lawyers from Kim & Chang LLC at an upscale bar in Cheongdam-dong. - The Daejang-dong land development scandal is said to have its roots in President Yoon’s tenure as a prosecutor, where he allegedly overlooked illegal loans by Busan Savings Bank, a matter connected to Yoon’s close aides. |

|

○ Fake news appealing to People Power Party supporters - The substantial deficit incurred by the Korea Electric Power Corporation (KEPCO) is due to the former administration’s nuclear phase-out policy. - There was election malpractice, including vote rigging, during the 2020 National Assembly Elections. - Evidence that North Korean hackers infiltrated the National Election Commission (NEC)’s election systern has been discovered. - Police patrol units are experiencing workforce shortage, due to the heightened investigative demands caused by the “complete deprivation of the prosecutorial investigative right (geom-su-wan-bak: 검수완박), a policy advocated by the Democratic Party. |

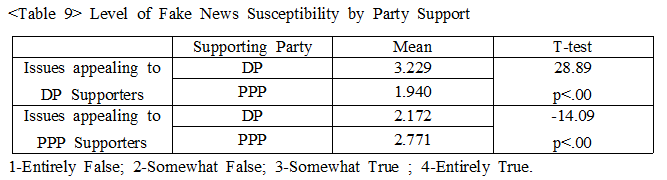

The average values for the two distinct categories of issues were analyzed to determine if individuals' acceptance of these categories aligns with their political affiliations. Table 9 illustrates significant variation in how supporters of different parties reacted to various fake news stories. Specifically, the reaction of Democratic Party (DP) supporters to fake news that resonated with them was markedly different—DP supporters were inclined to believe these stories, while People Power Party (PPP) supporters typically found them "somewhat unlikely."

Based on these findings, this paper analyzes various factors influencing susceptibility to disinformation. Table 10 incorporates fake news targeting DP and PPP supporters, and covers all eight aspects of disinformation as independent variables. It then sets the following nine distinct categories as dependent variables to perform a linear regression analysis.

- Populist characteristic: Public self-leadership, anti-elitism, politics of good vs. evil, confrontational politics

- Difference in political preference: │DP preference – PPP preference│,│Yoon preference – Lee preference│,│Yoon preference – Moon preference│

- Ideology: : Self-Perceived Ideology, Degree of Ideological Polarization

- Perception of the degree of social conflict: : Ruling vs. Opposition party, rich vs. poor, conservative vs. progressive, Youngnam vs. Honam region

- Trust for political institutions: : President, National Assembly, Executive branch, judicial court, Constitutional Court

- Personal political attributes: : degree of political interest, political knowledge

- Socioeconomic background: : age, gender, level of education

- Social class: : household income, assets, subjective sense of belonging to social class

- Place of birth: : Chungcheong, Jeolla, Daegu-North Gyeongsang, Busan-Ulsan-South Gyeongsang

The results highlighted the substantial influence of the "politics of good vs. evil" on vulnerability to disinformation, emphasizing a deep-seated division between "allies" and "enemies." This environment of confrontation, characterized by exclusion and antagonism towards adversaries, amplifies the challenge of discerning truth from falsehood. Such a political landscape aggravates polarization and may reinforce clique politics, fostering a setting conducive to increased susceptibility to fake news.

This feature is reaffirmed by the “perceived gravity of social conflict variable,” indicating that susceptibility to fake news increases with perceived ideological conflicts between progressives and conservatives. People tend to be more vulnerable to fake news as they align more strongly with ideological extremes. However, no significant differences were noted concerning political preferences or attitudes toward parties or political leadership.

In terms of trust in key political institutions, attitudes towards the National Assembly and the President differed based on party support. For the National Assembly, where DP holds the majority, individuals with greater trust in the National Assembly were more likely to believe fake news targeting DP supporters. Conversely, those with less trust in the National Assembly were more receptive to fake news aimed at PPP supporters. Trust in President Yoon, who is a member of the PPP, showed an opposite pattern: individuals with low trust in the President were more receptive to fake news favoring DP supporters, while those with high trust were more inclined to believe fake news favoring PPP supporters. Thus, fake news consumption is significantly influenced by party identification, highlighting that partisan polarization plays a critical role in the dynamics of fake news receptivity.

Dependent Variable: 1-Entirely False; 2-Somewhat False; 3-Somewhat True; 4-Entirely True.

Conflict Perception: 1-Extremely Serious, 5-Not Serious at All.

Trust in Institution: 0-Strong Distrust, 10-Strong Trust

Ideological Polarization: Self-Perceived Ideology Moderate 5 –1/ Progrssive 4, Conservative 6 - 2/ Progressive 3, Conservative 7 – 3/ Progresive 2, Conservative 8 – 4/ Progressive 1, Conservative 9 – 5/ Progressive 0, Conservative 10 -6

However, what merits particular attention regarding political institutions is the judiciary. As trust in the courts decreased, receptivity to disinformation increased. A lower level of trust in the Court by DP supporters and a lower level of trust in the Constitutional Court by PPP supporters heightened vulnerability to fake news. Both the judicial court and the Constitutional Court showed statistically significant results in all eight areas combined.

Further analysis reveals a clear age-related trend: younger individuals are more susceptible to disinformation. Geographically, a significant pattern emerged specifically in Jeolla Province. There, receptivity to narratives favoring DP supporters was notably high, while openness to those appealing to PPP supporters was low. This pattern reflects Jeolla Province's status as a stronghold for the DP in the Honam region.

In short, the prevalent susceptibility to disinformation in South Korea underscores the complexity of issues within its political landscape. The pervasive politics of good and evil, which is a hallmark of populist attitudes and partisan polarization, exacerbates people's vulnerability to fake news. Additionally, diminished trust in “institutional judges” such as the judiciary further increases susceptibility to disinformation.

4. Public Sentiment on Disinformation Regulation: Insights from the EAI Opinion Survey

This paper analyzed how partisan polarization and populist attitudes influence the receptivity to disinformation. The key findings are summarized as follows:

First, polarization was found to be extremely severe, characterized by an ideological rift that appears nearly irreconcilable. Supporters from both sides of the political spectrum tend to view their own party as moderate and the opposing party as extreme. They seemingly perceive that responsibility for the ideological distance lies with the opposing side. Additionally, a clear and consistent partisan attitude is observed in policy matters. This stance appears to be more a result of political mobilization by the party rather than a reflection of individual opinion formation. In other words, the political parties are actively "mobilizing" partisan polarization.

Moreover, the attitude towards populism is closely related to partisanship. The receptivity to populism increases when there is a perception that political institutions fail to meet the needs and hear the voices of the citizens. Specifically, susceptibility to populism intensifies when trust in the National Assembly is low or when individuals feel politically ineffective. In essence, the inadequate responsiveness of existing political institutions is amplifying populist sentiments.

The research also revealed that the confrontational politics of "good versus evil" significantly impacts receptivity to disinformation. The politics of disunion, which identifies and demonizes enemies as targets for exclusion and hatred, was found to influence the consumption of fake news.

Another particularly important finding relates to the role of judicial institutions. A low level of trust in the judiciary, including the Constitutional Court and courts in general, was seen to heighten susceptibility to disinformation.

The issue of disinformation is critically linked not only to political parties but also to a pervasive lack of trust in political systerns. This situation underscores the pressing need for political reform, aimed at fostering a more competitive and transparent political environment

References

Akkerman, Agnes, Mudde, Cas, and Andrej Zaslove. 2014. “How populist are the people? Measuring populist attitudes in voters.” Comparative Political Studies 47(9): 1324–1353.

Brody, Richard and Benjamin Page. 1972. “The Assessment of Policy Voting.” The American Political Science Review. 66(2), 450-458.

Cha, Taesuh. 2021. “The Tension between Liberalism and Democracy: The Advent of Populist Moment in South Korea [in Korean].” The Journal of Political Science & Communication 24, 3: 139-170.

Diaz Ruiz, Carlos and Thomas Nilsson. 2023. "Disinformation and Echo Chambers: How Disinformation Circulates in Social Media Through Identity-Driven Controversies." Journal of Public Policy & Marketing. 4 (1): 18–35.

Downs, Anthony. 1957. An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper.

Galston, William. 2018. “The Populist Challenge to Liberal Democracy.“ Journal of Democracy 29(2), 5-19.

Ha, Sang-eung. 2018. “Impact of Korean Voters’ Populist Tendency on Political Behavior [in Korean].” Journal of Legislative Studies 24, 1: 135-170.

Kang, Won-Taek. 2005. “Generation, Ideology and Transformation of South Korean Politics [in Korean].” Korean Association of Party Studies 4, 2: 193-217.

________. 2021. "Populist Politics and Reform Measures for Korean Democracy." In Korean Democracy in a Period of Major Transition: Commemorative Volume in Honor of Professor Lee Hong-gu's Milestone Birthday [in Korean], edited by Lee Jeong-bok et al. JoongAng Books.

Kim, Il Young. 2004. “Participatory Democracy or Neo-Liberal Populism: Populism Dispute under the Kim Dae Jung and the Rho Moo Hyun Governments [in Korean].” Journal of Legislative Studies 10, 1: 115-144.

Mudde, Cas. 2004. ‘The Populist Zeitgeist’, Government and Opposition, 39(4), 541-563.

Mudde, Cas and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser. 2017. Populism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Park, Kyung-mi, Jung Taek Han, and Jiho Lee. 2012. “The Constructive Characteristics of Ideological Conflicts in South Korea [in Korean].” Korean Association of Party Studies 11, 3: 127-154.

Park, Sang Hoon. 2020. “Why am I critical towards Direct Democracy [in Korean].” YOKSA WA HYONSIL: Quarterly Review of Korean History 115: 3-19.

Seo, Byung-hoon. 2008. Populism: The Crisis and Choice of Modern Democracy [in Korean]. Chaecksesang.

Stanley, Ben. 2008. “The thin ideology of populism.” Journal of Political Ideologies. 3(1), 95-110.

Taggart, Paul. 2000. Populism. Translated by Baek Young-min. 2017. Populism: Origins and Cases, and Its Relationship with Representative Democracy [in Korean]. Hanul.

■ KANG, Won-Taek is the Chair of EAI Democracy Research Center and a Professor of Political Science and International Relations at Seoul National University

■ Typeset by: Jisoo Park, Research Associate

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 208) | jspark@eai.or.kr

Center for Democracy Cooperation