1. Introduction

Thailand transitioned from junta-authoritarian rule to a democratic government before 1997, a significant continuation of the “Black May 1992” event. As a result, the 1997 Constitution was considered a democratic constitution based on the principle of constitutionalism. According to the 1997 Constitution, sovereignty is exercised by following the principle of separation of powers. The general public elects the government and parliament and serves as the impetus for forming several important state power inspection organizations known as constitutional organizations. These organizations, consisting of the National Anti-Corruption Commission, the Election Commission, the ombudsman, the National Human Rights Commission, and the State Audit Commission, are viewed as independent and are therefore not subject to cabinet control. After their inception in 1997 and subsequent 25 years of continuation, the structures and authorities of these organizations have undergone numerous changes, and the use of power has had significant impacts on people and democracy. However, Thai democracy was interrupted by the military coups d’état in 2006 and 2014.

This work investigates the overall structure of Thailand’s horizontal accountability by analyzing the roles and evolution of these organizations since their inception. Also studies are the effectiveness of Thailand’s current horizontal accountability on the development and strengthening of liberal democratic governance. Finally included in the investigation are the operation of checks and balances by the relevant organizations, the success and failure of the oversight procedures, and factors affecting the effectiveness of accountability.

This study uses documentary research by literature review on related issues and the relevant laws from articles, books, journals, and, official documents. Also explored are the case studies both in Thailand and in other countries. Moreover, representatives from academia, civil society, and other related organizations were interviewed. The research questions are: 1) Is the existing checking systеm by the executive and legislative branches sufficient and effective for democratic governance? 2) Is the judiciary branch independent or politically neutral enough to check and punish executive wrongdoings? and 3) Are oversight bodies performing well?

2. Literature Review on the Concept of Horizontal Accountability

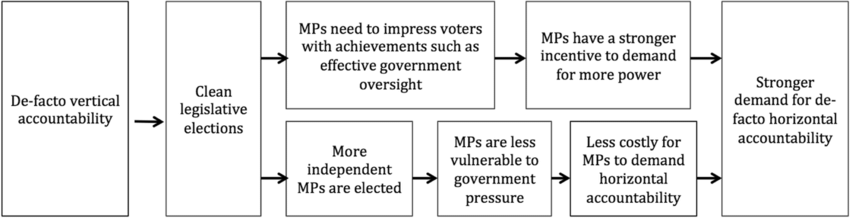

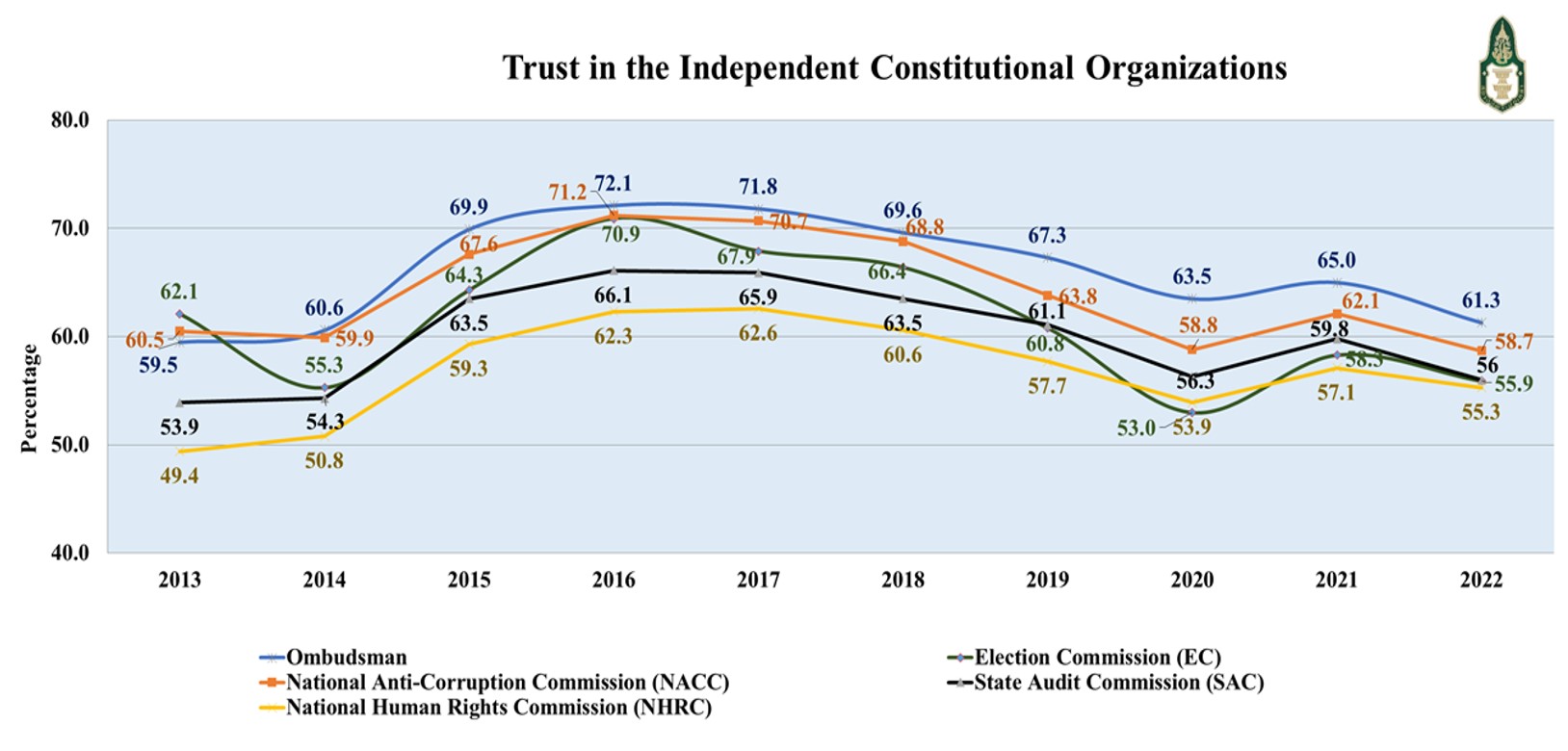

In the social sciences, the idea of accountability remains highly debated. Dahl (1971) and Wilson (2015) explain that it is beneficial if competition among elites develops before participation increases. However, Mechkova, Luhrmann, and Linberg (2017) hypothesize that in differentiating between institutions of diagonal accountability (media and civil society), vertical accountability (connected to elections and political parties), and horizontal accountability (checks and balances across institutions), pressure for horizontal accountability grows as vertical and diagonal accountability advances. Moreover, most de facto vertical accountability forms come before the other types of accountabilities (Mechkova, Luhrmann, and Linberg 2017, 3). Effective horizontal accountability structures, such as vigorous parliaments and independent high courts, Effective horizontal accountability structures, such as vigorous parliaments and independent high courts, emerge quite late in the process and build on advancements made in other areas. Following Figure 1, the desire for more horizontal accountability is anticipated to rise as vertical accountability levels rise. Two pathways illustrate how vertical accountability can enhance the demand for horizontal accountability (Mechkova, Luhrmann, and Linberg 2017, 13).

Figure 1. Two Pathways Illustrating How Vertical Accountability Can Enhance the Demand for Horizontal Accountability

Source: Mechkova, Luhrmann and Linberg 2017, 13

This paper investigates Thailand's horizontal accountability mechanisms, beginning with structural or legal considerations. Conducting a comparative study of the 1997, 2007, and 2017 Thai Constitutions to analyze the changing trend of Thailand's horizontal accountability mechanisms and to study the situation of horizontal accountability in Thailand using case examples demonstrates the effectiveness of this form of accountability as defined by the Constitution or law as law in action or de facto horizontal accountability that is not limited to law in book or de jure. In addition, the horizontal accountability in this study focus on the ability to check the government by the parliament, the courts, and the independent constitutional organizations.

3. Structure of Horizontal Accountability Mechanisms in Thailand

In Thailand, the 1997 Constitution is said to be one of the most democratic constitutions (Aphornsuvan 2001) and was the prototype of the principles of constitutionalism that appeared in subsequent constitutions until now.

We may classify the structure of horizontal accountability mechanisms in the provisions of the 1997, 2007, and 2017 Thai Constitutions the same way as we do actors, divided into three groups: legislature, judiciary and oversight institutions.

3.1. The role of the Legislature in Checks and Balances on the Government

The parliament is one of the three major political institutions that exercise sovereignty, as the legislative branch has important roles in legislation and the checks and balances of the administration. Since the change from absolute monarchy to constitutional monarchy in 1932, until now, there have been 20 constitutions (with 13 coup d’états). Although it started with unicameralism, Thailand currently utilizes a bicameral systеm. However, the provisions of the 1997, 2007, and 2017 Constitutions require Thai lawmakers to adopt a form of bicameralism, dividing the lower house into the House of Representatives and the upper house into the Senate. The origin of the legislation, comparing between 1997, 2007, and 2017, are as follows.

Table 1. Comparing the Origins of Oversights Institutions According to the 1997, 2007, and 2017 Constitutions

|

The origin of the legislature

|

The 1997 Constitution

|

The 2007 Constitution

|

The 2017 Constitution

|

|

members

|

The origin

|

members

|

The origin

|

members

|

The origin

|

|

House of representatives

|

500

|

- 100 from party-list

- 400 from the general election

|

480

|

- 80 from party-list

- 400 from the general election

|

500

|

- 100 from party-list

- 400 from the general election[1]

|

|

Senate

|

200

|

from the general election

|

150

|

- 77 from the general election

- 73 from appointment

|

200

|

from a selection

|

Powers and functions of the House of Representatives

The House of Representatives is responsible for providing checks and balances on the work of the government in several ways. Its primary role is to consider bills, but there are also roles to evaluate the annual expenditure budget; make the approval on an emergency decree; control the Administration of State Affairs; constitute a standing committee order to perform any act; inquire into facts or study any matter and report its findings to the House; and the approve of the appointment of a person as Prime Minister.

Powers and functions of the Senate

The three constitutions do not give the Senate the authority to propose bills; however, once the House of Representatives approves the bills, they are forwarded to the Senate for further consideration.

Together with the House of Representatives, the senators have the authority to review proposed legislation, authorize emergency decrees, and oversee state administration. Moreover, they can set up a standing committee, have the right to interpellate, and may submit a motion for a general debate without a resolution.

The Senate also has some powers that the House of Representatives does not have, including the ability to remove the prime minister, ministers, and other positions held in the legislative, judicial, and constitutional bodies. Anyone possessing unusually wealthy behavior, implied in the course of malpractice or indication exercising powers and duties, is contrary to the provisions of the law and Constitution.

The two houses of the National Assembly also have the responsibility to check the activity of constitutional organizations by approving the tasks of the commissions and reviewing their annual reports. The two houses established standing committees to exercise oversight of these organizations and the government.

3.2. Judiciary and Government Inspection Mechanisms

We can distinguish three judicial institutions responsible for monitoring the work of the Thai government, each with different jurisdictions in adjudicating disputes: the Constitutional Court, the Administrative Court, and The Supreme Court's Criminal Division for Holders of Political Positions.

Table 2. Comparing the Origins of the Judiciary Position According to the 1997, 2007, and 2017 Constitutions

|

The origin of the judiciary position

|

The 1997 Constitution

|

The 2007 Constitution

|

The 2017 Constitution

|

|

The Constitutional Court

|

Number of judges 11

|

Number of judges 8

|

Number of judges 9

|

|

The Administrative Court

|

A judge must be approved from the Judicial Commission of the Administrative Courts and the Senate.

|

|

The Supreme Court's criminal division for holders of political positions

|

Nine judges of the Supreme Court who are elected by a secret ballot at a general meeting of the Supreme Court and selected on a case-by-case basis

|

Adjusted the number of quorums to not less than 5 but not more than 9.

However, the quorum of the Supreme Court's Criminal Division for politicians on appeal under the latest Constitution stipulates that there are nine people.

|

Powers and functions of the Constitutional Court

The 1997, 2007, and 2017 Constitutions require the Constitutional Court to determine whether the bill or any organic law bill contains contents contrary to or inconsistent with the Constitution.

The Constitutional Court is also responsible for considering issues regarding the powers and duties of various organizations according to the Constitution. The decision of the Constitutional Court on the parliament, cabinet, courts, and other government bodies is final and binding.

In addition, the Constitutional Court has the role of adjudicating matters submitted by other courts, including the Courts of Justice, the Administrative Court, and the Military Court, if the Court considers that applying the provisions of the law to any case would be contrary to or inconsistent with the Constitution. The Constitution does not affect the Court's final judgment, including having the power to consider conflicts of authority between the parliament, the cabinet, or constitutional bodies that are not courts and can determine which emergency decree is an unavoidable emergency.

Powers and functions of the Administrative Court

The 1997, 2007, and 2017 Constitutions all stipulated that The Administrative Court has the power to try and adjudicate administrative cases arising from exercising legal administrative power or due to the conduct of administrative activities. Not included is the arbitration of an independent body, which is a direct exercise of their constitutional authority.

Powers and functions of the Supreme Court's Criminal Division for Holders of Political Positions

The 1997, 2007, and 2017 Constitutions stipulate that the Supreme Court's Criminal Division for Politicians should decide when the National Anti-Corruption Commission (NACC) finds a person holding a political position (such as a prime minister, minister, MP, senator, or other political officials' executives and members of local councils), as having an unusual increase in assets, the president of the NACC will submit a report on the investigation to the attorney general to prosecute the Supreme Court's Criminal Division for Politicians to ensure that the unusually increased assets belong to the state.

3.3. The Institutions According to the Thai Constitution

Institutions are responsible for monitoring the work of the government; and, according to the Constitution, may be called "independent constitutional bodies," namely the Election Commission, the National Anti-Corruption Commission, the State Audit Commission, the Ombudsman, and the National Human Rights Commission, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Comparing the Oversights Institutions According to the 1997, 2007, and 2017 Constitutions

|

The organizations

|

The 1997 Constitution

|

The 2007 Constitution

|

The 2017 Constitution

|

Note: the current set

|

|

The Election Commission

|

5 commissioners

A chairperson and four other members, appointed by the King upon the advice of the Senate

|

7 persons appointed by the King upon the recommendation of the Senate.

|

All seven were approved by the junta legislature.

|

|

The National Anti-Corruption Commission

|

9 commissioners appointed by the King upon the advice of the Senate from persons selected by the Selection Committee.

|

Two persons was approved before the 2014 coup, five persons were approved by the junta legislature in 2015, The rest have been endorsed by the current Senate, which originated from the NCPO.

|

|

The State Audit Commission

|

A Chairperson and nine other members appointed by the King upon the recommendation of the Senate.

|

Seven members appointed by the King upon the advice of the Senate.

|

All seven were approved by the junta legislature.

|

|

The Ombudsman

|

There are at most 3 people, set according to the advice of the Senate.

|

The junta legislature approved one; two were from the current Senate, sourced from the NCPO.

|

|

The National Human Rights Commission

|

A Chairperson and ten members appointed by The King upon the recommendation of the Senate.

|

A Chairman and six other members appointed by the King upon the recommendation of the Senate.

|

The junta legislature approved two, and five were from the current Senate, sourced from the NCPO.

|

Powers and functions of the Election Commission

The 1997 Constitution stipulates that the Election Commission is responsible for organizing or holding elections for members of the House of Representatives, senators, local councilors, and local admіnistrators, including the referendum, to be honest, and fair.

Powers and functions of the National Anti-Corruption Commission

The 1997 and 2007 Constitutions stipulate that the National Anti-Corruption Commission is responsible for auditing the assets and liabilities of persons holding political positions, including their spouses and minor children, every time they accept or leave their appointment and in the case of offenses against government positions. The later 2017 Constitution was similar but included the added role of investigating serious violations or non-compliance with ethical standards.

Powers and functions of the State Audit Commission

The 1997, 2007, and 2017 Constitutions similarly define the powers and duties of the State Audit Commission, the State Auditor, and the Office of the Auditor General of Thailand. The State Audit Office is responsible for auditing state finances, preparing reports, and following up on the performance of government spending and is an administrative agency. The Auditor General must supervise the organization. The State Audit Commission selects the Auditor General and oversees the work of the State Audit Office.

Powers and functions of the Ombudsman

The 1997, 2007, and 2017 Constitutions all stipulate that the ombudsman has the powers and duties to consider the investigation to find out the facts of the complaint. In case of non-compliance with the law, acting beyond legal authority, certain acts, or neglecting to perform duties of the administration, government officials, and relevant officials, they must also prepare a report and submit opinions and recommendations to the National Assembly. Further, they have the power to refer cases to the Constitutional Court or the Administrative Court when it is perceived that there are problems with constitutionality with the provisions of the law, rules, regulations, or actions of any government official.

Powers and functions of the National Human Rights Commission

The 1997, 2007, and 2017 Constitutions stipulate that the National Human Rights Commission is responsible for investigating and reporting acts or omissions that violate human rights and proposing appropriate remedial measures to the person or agency carrying out such actions or violations. If the proposed actions are not taken, the Commission must report to parliament for further action and recommend policies and proposals to improve laws, rules, or regulations to the National Assembly and the Cabinet to promote and protect human rights, including other related duties.

There are also audit mechanisms within the administration that do not have the status of a constitutional organizations and are organizations under the control of the administration itself, including the Department of Special Investigation (DSI) and the Office of the National Anti-Corruption Commission (NACC), and the Anti-Corruption Commission (PACC).

3.4. Structure of Horizontal Accountability Mechanisms in Thailand

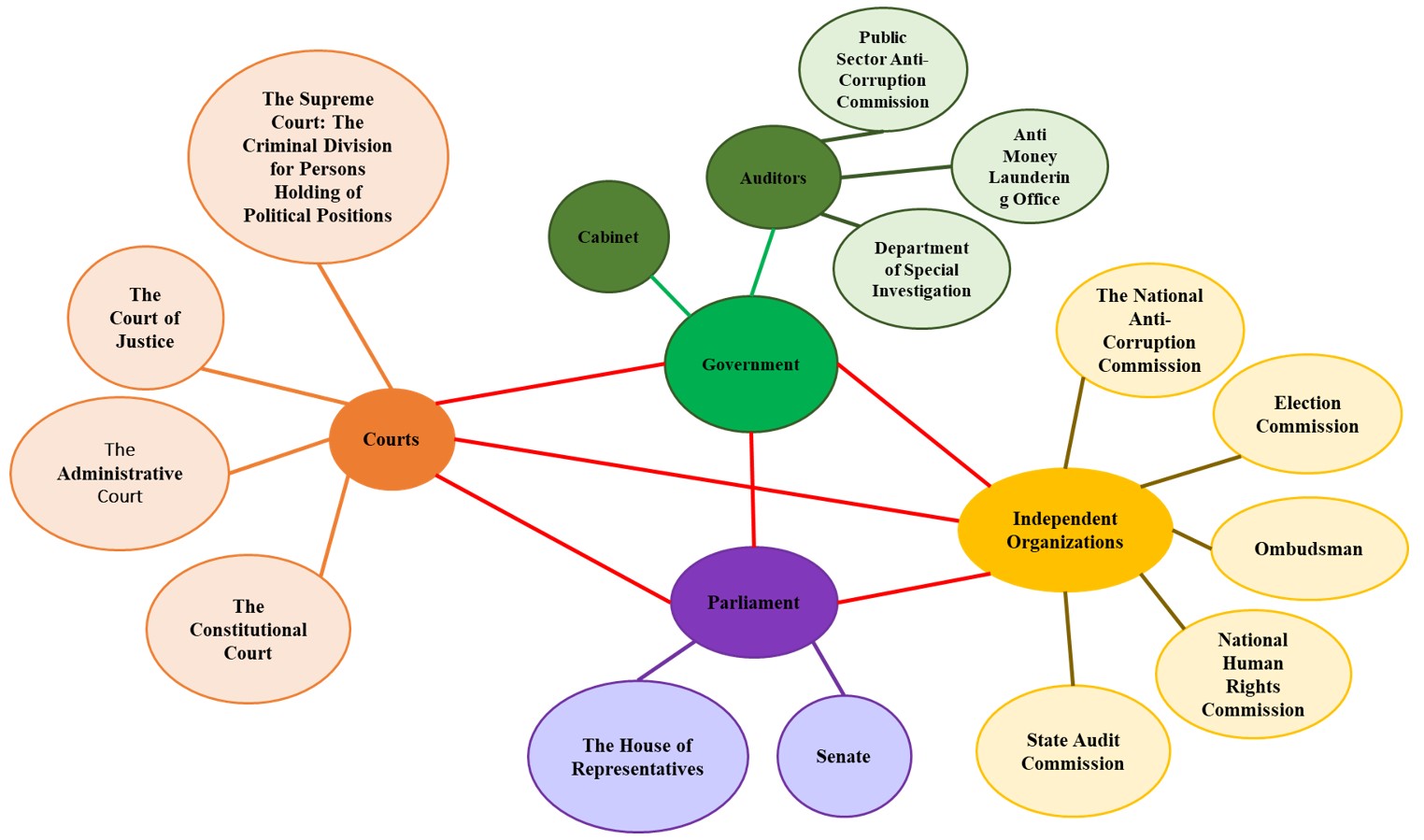

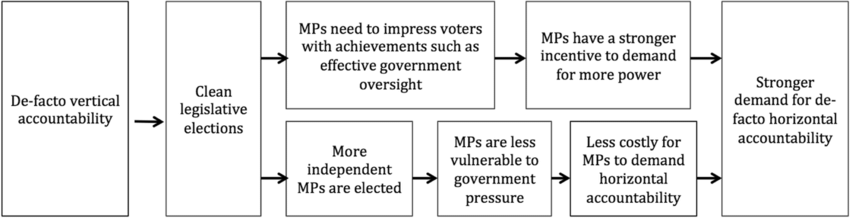

Figure 2. Structure of Horizontal Accountability Mechanisms in Thailand

Source: Illustrated by the authors

The design of horizontal accountability mechanisms to monitor the work of the government in Thailand has gradually matured in the dimensions of the number of organizations, organizational structure powers, and duties of the organizations, influenced by the organizations operating checks and balances and constitutionalism principles following the liberal democratic state since the 1997 Constitution. However, the origin of the entering source of the said organizations changed after the coup in 2006 through the design of the 2007 Constitution. Furthermore, the same action appeared again during the 2014 coup, in which the positioning of horizontal accountability actors shifted subtly and complexly, as distinguished by three interconnected factors.

Firstly, there has been a change in the origin of the Senate by progressively reducing its connection with the people. Initially, the 1997 Constitution required that general elections elect all senators. The 2007 Constitution later stipulated that almost half of the senators were not appointed through general elections. Ultimately, the 2017 Constitution requires that all senators not receive appointments through general elections. The manner of this designation is to ensure that senators do not have a source directly connected to the people.

Secondly, the change in the origin of the Senate has directly affected the senators’ roles in monitoring the government's work. It has also had a complex impact on the horizontal accountability systеm. Due to the origin of oversight institutions, the 1997, 2007 and 2017 Constitutions require those entering oversight institutions to obtain approval from the Senate. In addition, those appointed to the role of a judge in the Constitutional Court or the Supreme Administrative Court must also be approved by senators.

Thirdly, according to the interim provisions of the 2017 Constitution, the current senators originated from the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO). The current government also results from the approval of the House of Representatives and the Senate mentioned above due to the election to elect the Prime Minister of Thailand in 2019. This batch of 250 senators voted for General Prayuth Chan-o-cha as prime minister with 249 votes and one abstention. According to the current Constitution, the current government and oversight institutions also derive from the senators. Therefore, designing a mechanism to oversee institutions with such origins to monitor government work could be more effective due to the need for more independence between the organizations to deal with invisible relationships and powers between the incumbent.

Thirdly, according to the interim provisions of the 2017 Constitution, the current senators originated from the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO). The current government also results from the approval of the House of Representatives and the Senate mentioned above due to the election to elect the Prime Minister of Thailand in 2019. This batch of 250 senators voted for General Prayuth Chan-o-cha as prime minister with 249 votes and one abstention. According to the current Constitution, the current government and oversight institutions also derive from the senators. Therefore, designing a mechanism to oversee institutions with such origins to monitor government work could be more effective due to the need for more independence between the organizations to deal with invisible relationships and powers between the incumbent.

4. The Effectiveness and Trust in the Oversight Bodies

4.1. The Situation from the Perception of People

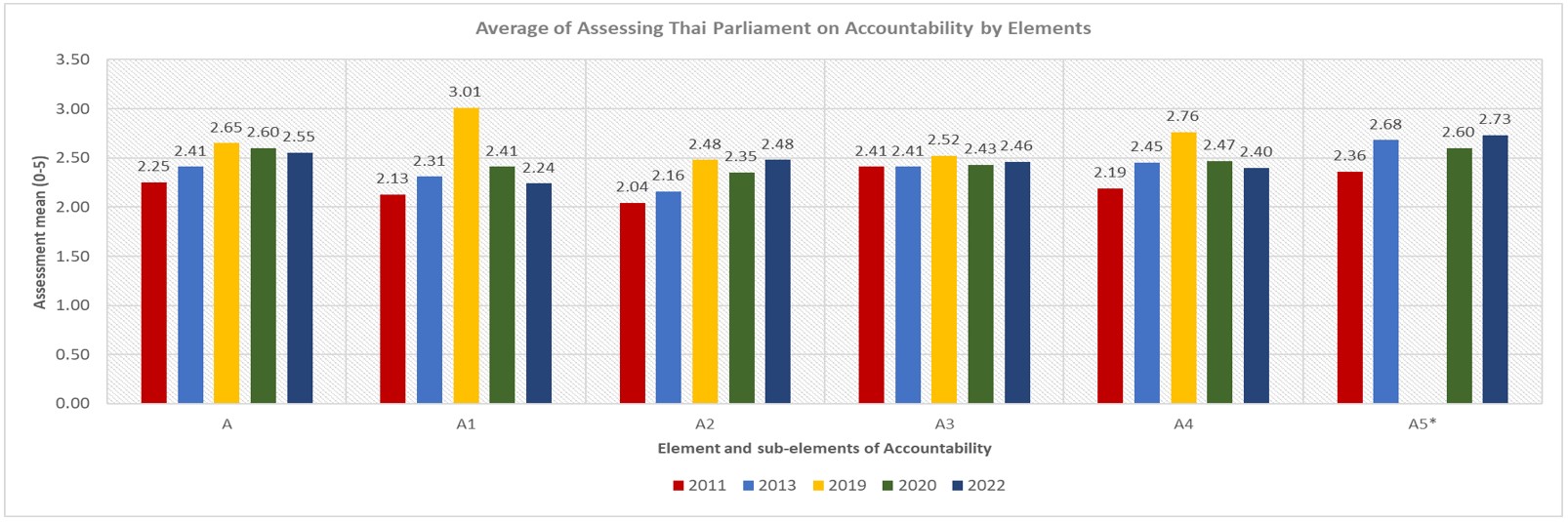

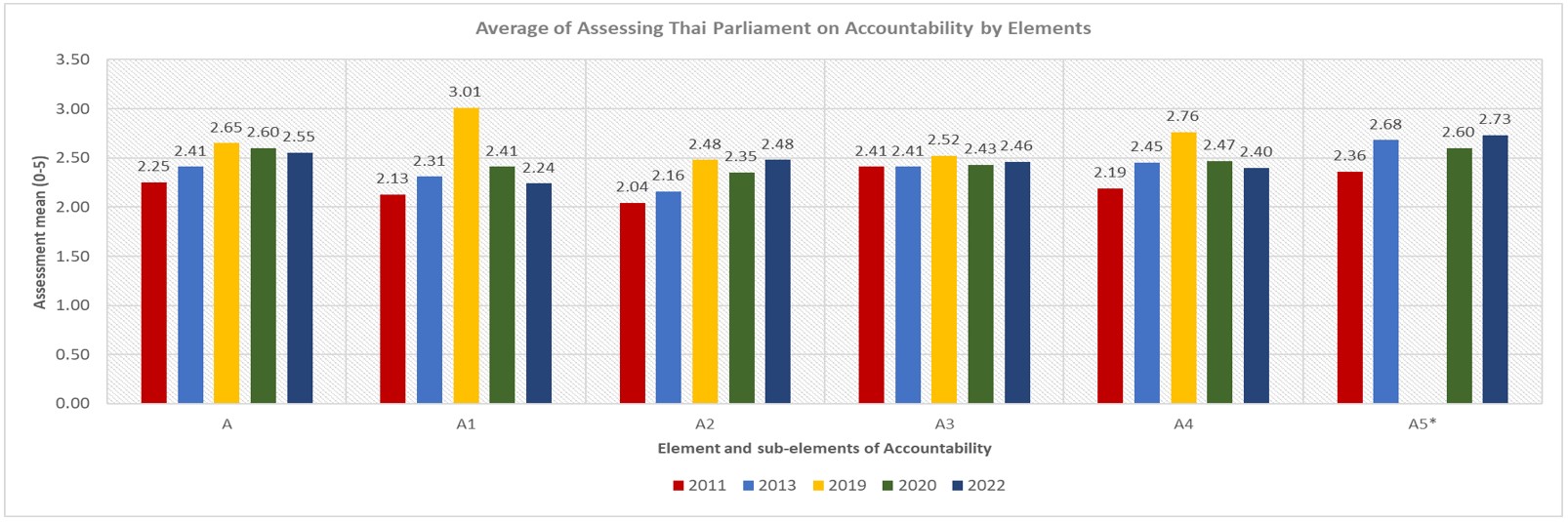

King Prajadhipok’s Institute conducts research on ‘Assessing Thai Parliament Using Inter-Parliamentary Union Indicators’. There are five components.[2]

Figure 3. The Assessment of Thai Parliament on Accountability

Source: King Prajadhipok’s Institute 2019, 2020, 2022

According to this study, the Institute found that the overall accountability assessment level results were moderate, with averages of 2.25, 2.41, 2.65, 2.60 and 2.55, respectively. The element regarding accountability with a higher mean ratio than others were the oversight of Subsidizing to Political Parties by the Election Commission (A3) and the Potential Development of Members of Parliament (A5). The Accountability of Members of Parliament to Citizens Nationwide (A1) was the only element with a high score level in 2019 (an average of 3.01 out of 5, the maximum score).

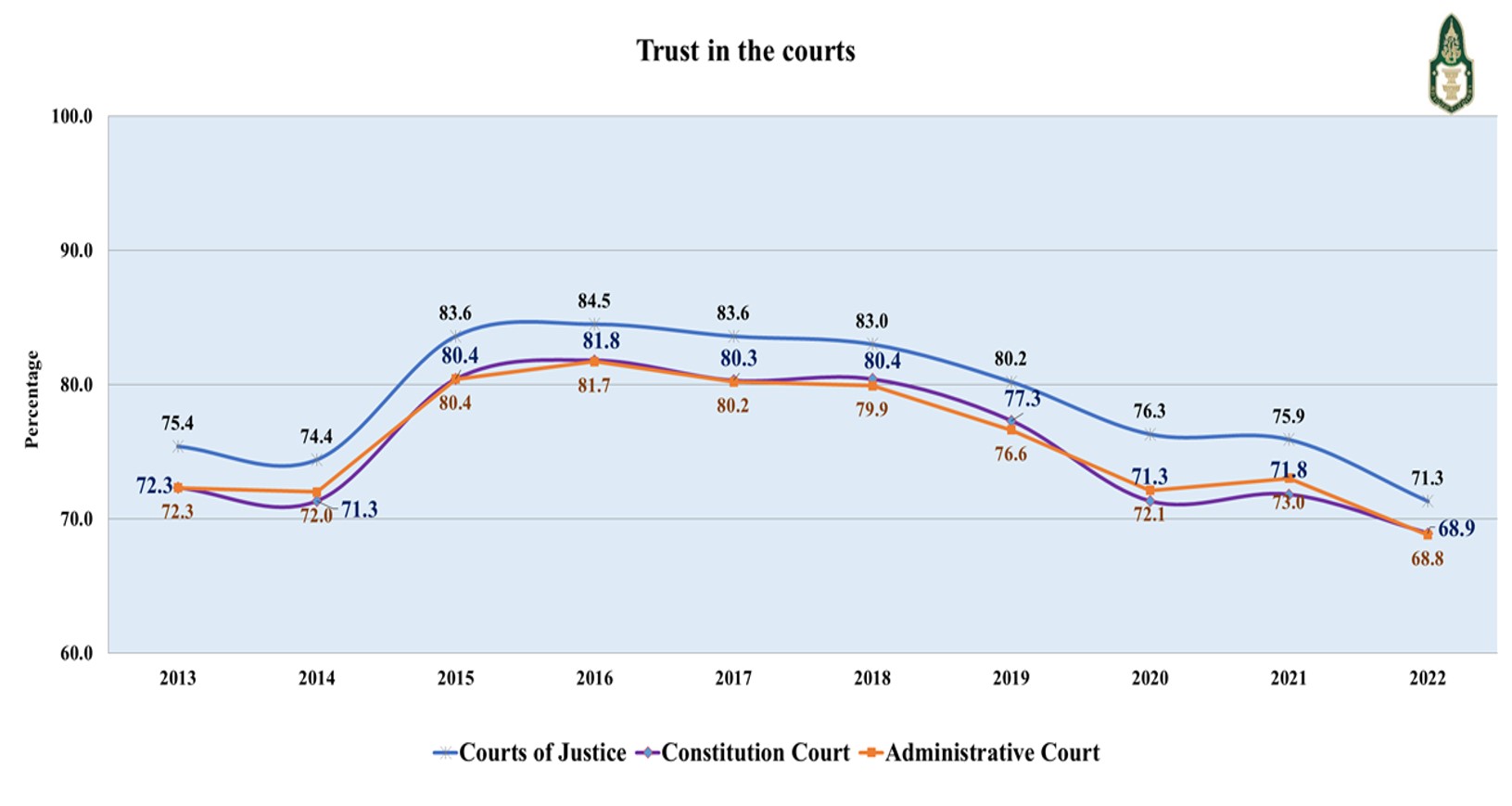

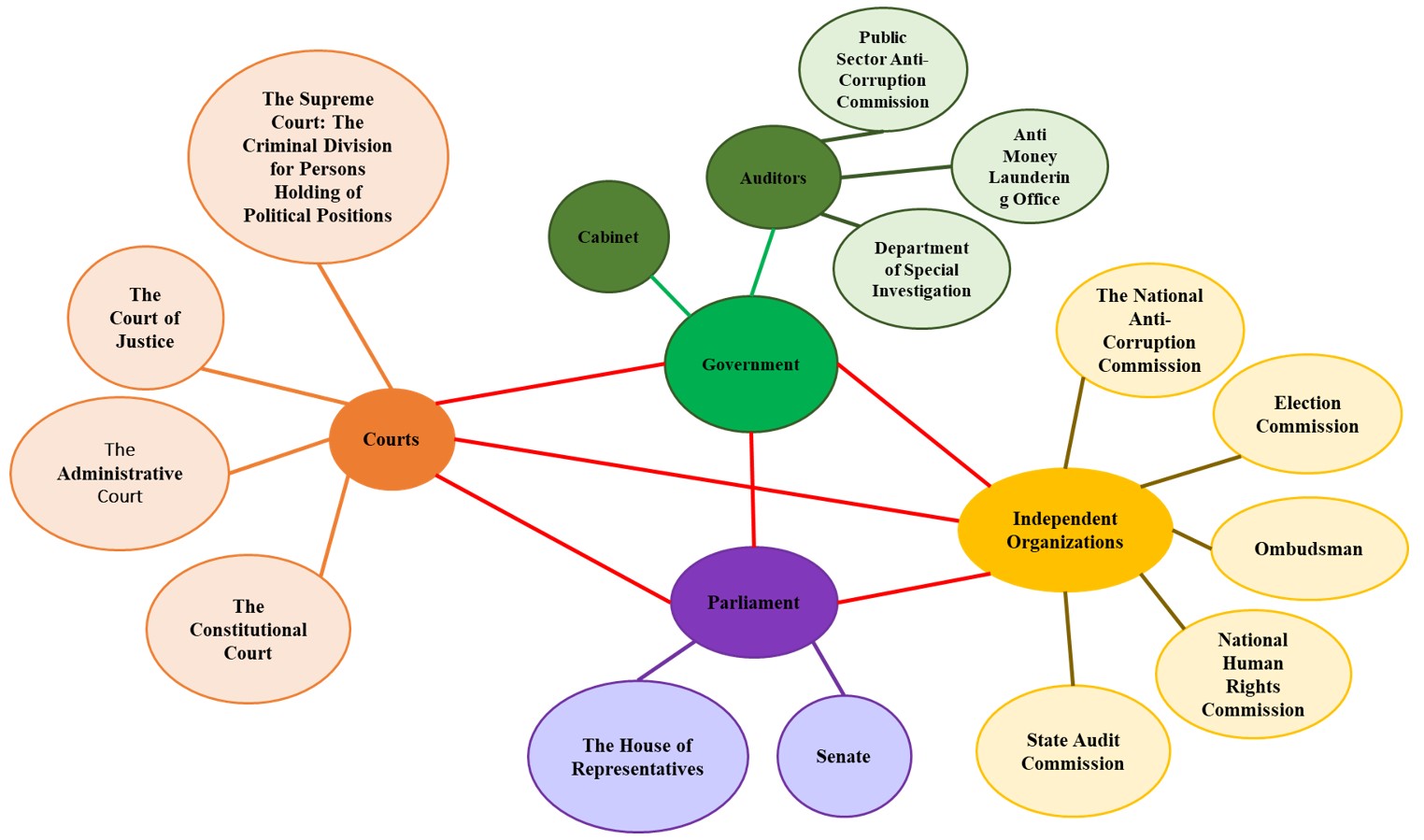

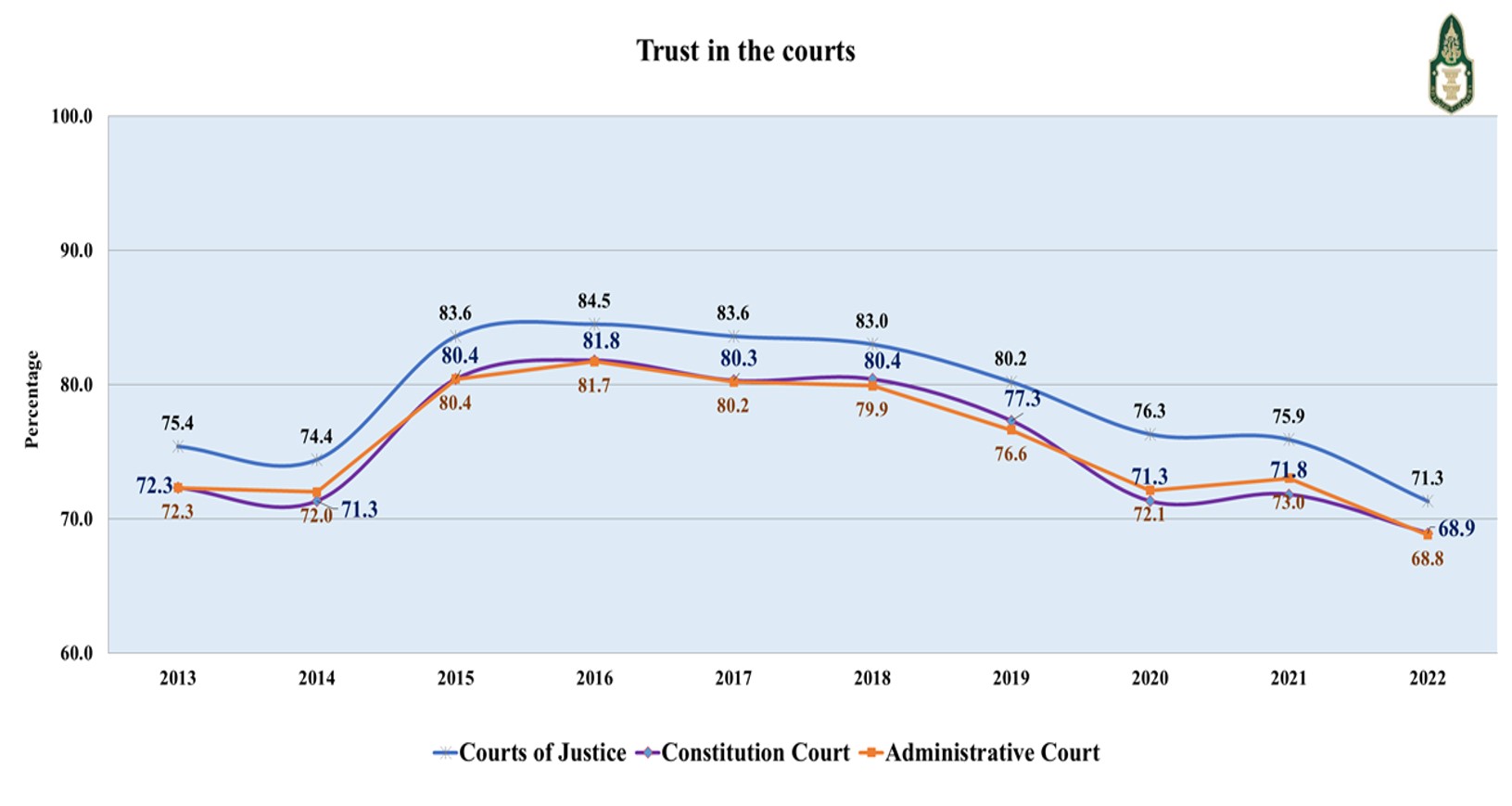

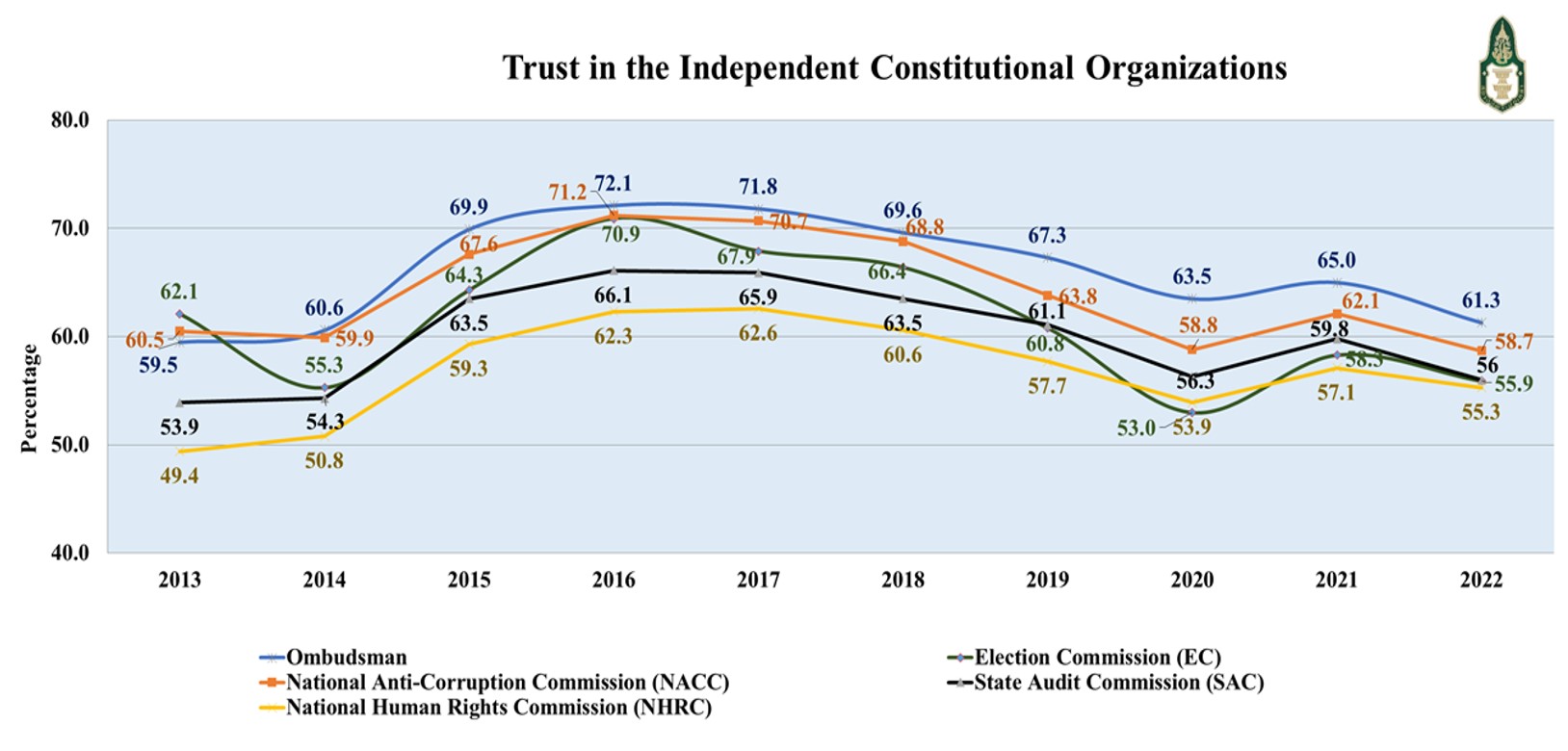

Furthermore, King Prajadhipok’s Institute has also studied institutional trust, especially in courts and independent constitutional organizations. According to survey results, even though most Thai people trusted the courts, referring to the fact that the answers ‘somewhat trust’ and ‘strongly trust’ resulted in more than 70 percent of the vote, they gradually decreased in 2022, especially trust in the Constitutional Court and the Administration Court. Moreover, Thai people trusted the work of independent organizations at a moderate level. The highest level of trust was in the ombudsman, and the lowest was in the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC). However, the level of trust has decreased in every organization overall (King Prajadhipok’s Institute 2022).

Figure 4. The Percentage of Trust in the Courts, and the Independent Constitutional Organizations

Source: King Prajadhipok’s Institute 2022

4.2. Case studies

The Election Commission (EC)

This case is about the malfunction in checking election transparency by the EC.

One candidate from Pheu Thai Party, Mr. Suraphon Kietchaiyakorn, led within Chiang Mai’s Constituency before he was disqualified and received an orange card, which meant he could not contest the election in the future because he donated 2000 baht to a monk. The Election Division in The Supreme Court denied this poll-fraud case, to which he lodged the EC in contempt. The case was dismissed, but the EC was required to pay 70 million baht by the Chiang Mai court (Bangkok Post 2022). Thus, the discretion of The Election Commission needs to be more careful and concise than before because otherwise, it may be countersued, causing the state to use the public's money for compensation.

The National Human Rights Commission of Thailand (NHRCT)

This case is about the limited function and power of NHRCT for other agencies to agree to resolve human rights abuses following the recommendation of NHRCT.

According to the responsibilities of NHRCT[3], they must give suggestions to the relevant agencies in order to prevent human rights violations. However, they lack the empowerment to force the authorities and may make them work without independence. Therefore, NHRCT requests that the executive and legislative branches revise the relevant laws and give them more power (Office of the National Human Rights Commission of Thailand 2021).

5. Recommendations

5.1. Policy Recommendations

The separation of power systеms should be strengthened, by firmly establishing the rule of law, and enforcement of the mandate of the Constitution.

Increased strength and support should be provided to those with a role in balancing the power of parliamentarians through various mechanisms, starting with educating these people about their roles and responsibilities and the performance of parliamentarians. Moreover, the relevant agencies should provide information and a public space for people to express their opinions.

Parliament should establish participation processes to allow members of civil society to play roles and give voices on behalf of the people, especially vulnerable groups such as the disabled, ethnic groups, or LGBTQ+ groups.

The state or the relevant agencies should provide accurate and accessible information, in order to be the mechanism to investigate the exercise of state power. Moreover, create networks of various sectors, including the public, private, and local government organizations, to assist in the investigation of complaints and to monitor the resolution based on the results.

5.2. Legal Recommendations

The provisions of the Constitution on the entry should be amended into a position within a constitutional oversight institution for the true independence of such organizations by stipulating that the generally elected senators approve entry into the said position. ■

References

Aphornsuvan, Thanet. 2001. The Search for Order: Constitutions and Human Rights in Thai Political History. https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/42075

Bangkok Post. 2022. “EC Silent on Surapol’s Election Case.” April 22. https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/politics/2298442/ec-silent-on-surapols-election-case

Dahl, Robert Alan. 1971. Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition. New Haven: Yale University Press.

King Prajadhipok’s Institute. 2019. Assessment of Thai Parliament Based on Inter - Parliamentary Union. Bangkok: King Prajadhipok’s Institute.

______. 2020. Assessment of Thai Parliament Based on Inter - Parliamentary Union. Bangkok: King Prajadhipok’s Institute.

______. 2022. Assessment of Thai Parliament Based on Inter - Parliamentary Union. Bangkok: King Prajadhipok’s Institute.

______. 2023. Assessing Public Trust in Various Institutions and Satisfaction with Public Services. Bangkok: King Prajadhipok’s Institute.

Mechkova, Valeriya, Anna Lührmann, and Staffan I. Lindberg. 2017. The Accountability Sequence: From De-Jure to De-Facto Constraints on Governments. The Varieties of Democracy Institute Working Paper Series 2017:58. https://gupea.ub.gu.se/handle/2077/54331

Office of the National Human Rights Commission of Thailand. 2021. Executive Summary: National Human Rights Commission Performance Report Fiscal Year 2021. https://www.nhrc.or.th/getattachment/eb42fc89-4435-46ef-a9b6-1c300a1bdde5/Executive-Summary-NHRCT-Annual-Report-for-Fiscal-Y.aspx

Wilson, Matthew Charles. 2015. Castling The King: Institutional Sequencing and Regime Change. Electronic Theses and Dissertations for Graduate, Pennsylvania State University.

[1] The 2017 Constitution of Thailand (Revised 2022)

[2] There are 5 components, consisting of the accountability of the parliament (A) consists of 5 components, 1) Accountability of Members of Parliament to Citizens Nationwide (A1), 2) Oversight and Punishment of Members of Parliament with Immoral Behavior are Related to Conflicts of Interests (A2), 3) Oversight of Subsidizing to Political Parties by the Election Commission (A3), 4) Oversight on Public Faith in Parliament (A4), and 5) Potential Development of Members of Parliament (A5). There are five levels: score 0.00 – 1.00 = very low, scores 1.01 – 2.00 = low, scores 2.01 – 3.00 = medium, scores 3.01 – 4.00 = high and scores 4.01 – 5.00 = very high.

[3] Section 45 of the Organic Act on the National Human Rights Commission of 2017

■ Thawilwadee Bureekul is the Deputy Secretary General of King Prajadhipok’s Institute (KPI) where she is involved in the planning, management, implementation, and coordination of the Institute’s research projects. In addition to her role at KPI, Dr. Bureekul is a professor at several universities in Thailand, including the Asian Institute of Technology, Thammasat University, Burapha University, Mahidol University, and Silpakorn University. She succeeded in proposing “Gender Responsive Budgeting” in the Thai Constitution, and she was granted the “Woman of the Year 2018” award and received the outstanding award on “Rights Projection and Strengthening Gender Equality” in the Year 2022 as a result.

■ Ratchawadee Sangmahamad is a senior academic of the Research and Development Office at King Prajadhipok’s Institute. Her research focuses on gender, citizenship, election studies, and conducting the quantitative research. She has published books as a co-author, such as Value Culture and Thermometer of Democracy, Thai Citizens: Democratic Civic Education, Thai Women and Elections: Opportunities for Equality, and many articles.

■ Arithat Bunthueng is a law school Lecturer at Payap University. He had previously worked as an academic in the Research and Development Office at King Prajadhipok’s Institute. He graduated in public law with interest in and worked on projects related to the rule of law, the liberal democratic state, law and society, decentralization of local government, Indigenous people’s rights, and human rights.

■ Typeset by Hansu Park, Research Associate

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 204) | hspark@eai.or.kr

![[ADRN Working Paper] Making Horizontal Accountability: A Case Study of Thailand](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/20230503164133108663727.jpg)

![[ADRN Working Paper] Horizontal Accountability in Asia: Country Cases (Final Report Ⅰ)](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/20240305162413775004648(1).jpg)

![[ADRN Working Paper] Assessing Horizontal Accountability in Mongolia: Weak Judiciary Combatting Corruption Scandals](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/2023091323225176354522(1).jpg)