![[ADRN Working Paper] Direct Democracy in Thailand](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/202205271459261069922048.jpg)

[ADRN Working Paper] Direct Democracy in Thailand

Working Paper | 2022-05-27

Thawilwadee Bureekul

King Prajadhipok’s Institute

Ratchawadee Sangmahamad

King Prajadhipok’s Institute

Arithat Bunthueng

King Prajadhipok’s Institute

As a part of the 2021/22 Asia Democracy Research Network’s Direct Democracy research group, EAI launched a working paper series composed of seven working papers, covering the cases of Indonesia, India, Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Mongolia, and Malaysia.

In this working paper, Thawilwadee Bureekul, Ratchawadee Sangmahamad, and Arithat Bunthueng at the King Prajadhipok’s Institute examine the current state of direct democracy in Thailand and explore ways to strengthen the mechanisms of direct democracy. The authors argue that the mechanisms such as referendums, law initiatives, recalls, and unconventional political participation show positive signs of direct democracy along with the technological development in the country. However, they warned that they will be only sustainable and effective with political will and civic support.

Introduction

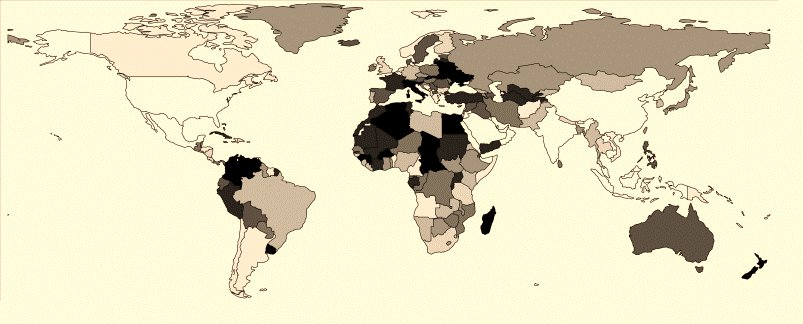

Direct democracy is a form of democracy beyond representative democracy. It is the basic political process which allows ordinary citizens to not only vote for their representatives in the parliament, but also participate in political activities and policy decisions (John G. Matsusaka 2005, 187). Moreover, direct democracy is used by the communication technology revolution, and is the better tool when policymakers require deep information that experts do not know (John G. Matsusaka 2005, 186). Nowadays, popular initiatives and referendums are the key mechanisms of direct democracy. According to the V-Dem Institute’s report (2015), the use of direct democracy has been increasing worldwide. However, citizens still face challenges in accessing their right to participate in direct democracy due to a lack of measures to participate in direct democracy and a lower capability in assessing its quality (David Altman 2015). In the V-Dem Institute report, direct democracy (DD) refers to the institutionalized process by which citizens of each country register their opinions on a specific issue via a ballot, consisting of initiatives, referendums, and plebiscites. This definition excludes recall elections and deliberative assemblies. Figure 1 illustrates the score of Direct Democracy Practice Potential (DDPP) around the world. [1] Darker shades indicate higher DDPP. The maximum score is 0.849, the minimum score is 0, and the mean score is 0.162. Thailand’s score is 0.088, among which its obligatory referendums (OR) score is 0.306, and its popular initiative (PI) score is 0.048 (David Altman 2015).

Since 1932, Thailand has changed from an absolute monarchy to a constitutional monarchy. This means that Thailand has moved forward with democracy. In ninety years, Thailand has had 20 constitutions and charters with a series of intervening military coups. In the events of 1997, the National Assembly elected a Constitution Drafting Assembly to hold a public hearing over what the new constitution should contain. This 1997 Constitution is called the “People’s Constitution,” and included a section related to law initiative in which by 50,000 eligible voters can propose a law. In the 2007 Constitution which followed, just 10,000 eligible voters can propose a law. The 2017 Constitution also mandates law initiative by eligible votes at both the national and local level. At the local level, residents can propose local ordinances. So far, in addition to the law initiative implemented in Thailand, popular direct democracy through unconventional political participation has appeared. One example is the use of artificial intelligence (AI) by young people and social media to engage in direct democracy. Direct democracy in Thailand is accordingly more important and widely experienced compared to the past. A greater number of people are participating in direct democracy. In this study, the authors would like to study the current state of direct democracy in Thailand and explore how it might be strengthened.

Figure 1. Direct Democracy Practice Potential (DDPP) around the world (2000)

Source: Photo by David Altman, [12] orchestrated the constitution drafting process and the process of referendum was marred by severe restrictions on people’s ability to debate and criticize the content of the draft charter. Moreover, a draft constitution written by an army-appointed committee and has content entrench military control by proposes that the appointed senate should be involved in selecting a prime minister.

Figure 2. Provinces of Thailand colored according to referendum results (Charter)

|

|

|

|

Year 2006 |

Year 2016 |

Source: Photo from Wikipedia, February 10, 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2007_Thai_constitutional_referendum; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2016_Thai_constitutional_referendum

The first referendum showed a turnout rate of 57.61 percent of registered voters. Of those who voted, 57.81 percent approved and 42.19 percent disapproved. Thus, the military government would have had the freedom to choose any previous constitution to adapt and promulgate instead. For the second time, the charter offered only semi-democracy and was seen to tighten military rule in Thailand. However, it was approved by 61.35 percent and disapproved by 38.65 percent of voters, with a voter turnout of 59 percent. Moreover, a second proposal for the next Prime Minister to be jointly elected by Senators and MPs was also approved (the Secretariat Office of the House of Representatives, 2022). Below are the referendum results on the draft charter, with a comparison of the provinces of Thailand between 2006 and 2016.

2) Law initiatives

Under the 1997 Constitution and the 1999 Initiative Process Act, there are many conditions for participating in law initiatives that make it more difficult to fulfill the process. Examples include the number of names of qualified eligible voters required, supporting documents, and methods of by which the names must be entered. During implementing the 1997 Constitution, sixteen bills were proposed, with only one legal draft being adopted and promulgated by the parliament. Under the 2007 Constitution, there were 51 draft laws submitted to the parliament, with eight of them being adopted by the parliament and enacted into law. In addition, the number of eligible voters who can propose a law has been reduced from 50,000 to 10,000, although 50,000 are still required for a proposed constitution. Under the 2017 Constitution, people can more easily submit a bill by using only one copy of their identity card. It is not necessary to provide a copy of one’s household registration. As of February 23, 2022, there have been 71 law proposals put forth under this method, but none of them have been passed into law yet. However, the process of initiating the law under the Initiative Process Act C.E. 2021, which was promulgated May 27, 2021, makes it easier for people to bring in legislation. Admitting the entry into the introducing bill without having to sign in the case of submitting a bill proposal through the online system. [13] With the previous law requires signature on the specified from along with a copy of the identity card. Because the current legal initiative system is electronic, it is more practical than systems of the past, and people are therefore more likely to proposed laws. The trend of public participation and the government's ability to allow people to directly participate in politics through the channels of law initiatives are positive signs of direct democracy. However, there are some constraints to consider, such as political will and the prime minister's endorsement of the public's proposed bills related to demanding financial support from government, concerns taxation or government spending so-called money-bill” [14] . In addition, legislative amendments to the bill may also distort the intent of the bill's proponents.

3) Recalls

In Thailand, the recall mechanism is frequently used as a political tool by authoritarian dictatorships rather than to promote democracy. This is because there has never been a recall mechanism that can remove a person from office under democratic governments, whereas a recall mechanism has been used to remove people from political office or high-level positions in order to maintain authoritarianism by the legislature that stems from appointment after a coup. The first was the recall of a member of the Human Rights Commission by resolution of the National Legislative Assembly appointed after the coup in 2006. There was also the recall of former Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra by resolutions of the National Legislative Assembly, which was appointed after the 2014 coup, and so on. Furthermore, while the recall mechanism for political office holders and high-ranking positions is not endorsed by the existing constitution, there are political movements to recall incumbents through a signature campaign on the website www.change.org. For example, Ms. Parena Kraikup, a member of the House of Representatives from the Palang Pracharath Party, received more than 75,196 signatures on a petition demanding her recall for inappropriate behavior and not setting a good example for the people. The petition for the Election Commission's recall has more than 861,843 supporters. These campaigns are symbolic representations of the people's political will, although such signatures have no legal effect (the Secretariat Office of the House of Representatives, 2022).

4) Unconventional political participation

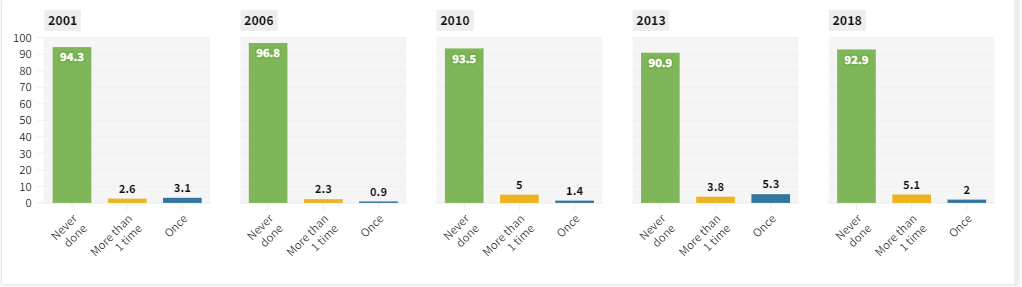

The other form of direct democracy is unconventional political participation (UPP) (King Prajadhipok’s Institute, 2014). Examples include getting together with others to raise an issue or sign a petition, attending a demonstration or protest march, and using force or violence for a political cause. The following figure shows responses from the Asian Barometer 2018 survey to those asked whether they had ever attended a demonstration or protest march.

Figure 3. Percentage of people attending a demonstration or protest march, by year

Source: Data adapted from King Prajadhipok’s Institute, Asian Barometer Survey, 2018

According to Figure 3, most people have never attended a demonstration or protest march before. However, this percentage decreased after 2006. It seems that after Thailand had the first referendum in 2006, people participated more in political activities. In May 2014, there was a coup d’état in response to the political situation after months of political demonstrations, a disrupted and ultimately invalidated election, and accusations of government mismanagement. Thus, it can be said that unconventional political participation has become a signal that the temperature of politics is high and more government attention should be paid to the voices of the public.

Problems of Direct Democracy in Thailand

1) Referendums have become a political mechanism and no longer reflect the will of the public.

2) While the number of people proposing bills through the law initiative mechanism has increased, not many bills can pass the parliament and become law because bills related to the budget have to be endorsed by the Prime Minister. In addition, people have a limited amount of the Civil society helps strengthen direct democracy and supports law initiatives.

3) Recalls seem to be impossible.

4) The other form of direct democracy is popular democracy.The importance of this mechanism appears to be increasing because of the application of social media and websites like www.change.org, which have become tools through which to send a signal to the government, especially on important issues. Unconventional forms of political participation, like demonstrations on the streets through car mobs or other such forms, and the application of social media, have become an increasing role, more than conventional forms. However, people who join in acts of popular democracy risk violating the law.

The Trend of Direct Democracy in Thailand

The authors see positive signs of direct democracy in Thailand, especially in law initiatives, because the new law promulgated according to the 2017 Constitution allowed for the application of social media in lawmaking, while the previous law did not. With the adoption of technology to support law initiatives, the authors think that forms of direct democracy, especially law initiatives, will increase in their importance. However, without political will and support for these mechanisms, the law initiatives will not be realized. Since both representative democracy and direct democracy are a foundation of democratic regime, which consistent and support each other. Therefore, the stability of representative democracy and intention of promoting direct democracy from the government and the politicians are important. Otherwise, if people could not participate in direct democracy via the legally conventional channels, it may lead people to have the movement along the road or the unconventional political participation. Thus, the direct democracy’s drive (conventional form) in Thailand may encounter unceasing obstacles, as same as ‘walking to the pointless’ under the unsteady Thai democratic regime in the current.

References

Altman, David. “Measuring the Potential of Direct Democracy Around the World (1900-2014)” V-Dem Working Paper 2015:17 (December 1, 2015), SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2701164.

Beramendi, Virginia, et al. Direct Democracy: The International IDEA Handbook. Stockholm: International IDEA, 2008. https://www.idea.int/publications/catalogue/direct-democracy-international-idea-handbook.

Bobbio, Norberto. Liberalism and Democracy. Translated by Martin Ryle, and Kate Soper. London: New Left Books, 1990.

Bulmer, Elliot. Direct Democracy: International IDEA Constitution-Building Primer 3. Stockholm: International IDEA, 2014. https://www.idea.int/publications/catalogue/direct-democracy.

Bureekul, Thawilwadee, and Ratchawadee Sangmahamad. Value Culture and The Thermometer of Democracy. Bangkok: King Prajadhipok’s Institute, 2014.

Bureekul, Thawilwadee, Tossapon Sompong, and Somkiet Nakratok. The Study of Citizenship Behavior for Thai Society. Bangkok: King Prajadhipok’s Institute, 2020.

Collin, Kathy. “Populist and authoritarian referendums: The role of direct democracy in democratic deconsolidation.” The Brookings Institution, (2019). https://www.brookings.edu/research/populist-and-authoritarian-referendums-the-role-of-direct-democracy-in-democratic-deconsolidation/.

International Federation for Human Rights. Roadblock to Democracy: Military repression and Thailand’s draft constitution, 2016. https://www.fidh.org/IMG/pdf/fidh_report_thailand_roadblock_to_democracy.pdf.

Kurlantzick, Joshua. “Thailand’s August 7 Referendum: Some Background.” Council on Forieng Relations. August 3, 2016. https://www.cfr.org/blog/thailands-august-7-referendum-some-background.

Kyburz, Stephan and Stefan Schlegal. “8 Principles of Direct Democracy.” Center for Global Development. July 29, 2019. https://www.cgdev.org/blog/8-principles-direct-democracy.

Matsusaka, John G. “Direct Democracy Works.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Volume 19, no. 2 (Spring 2005): 185-206.

“Thai referendum: Why Thais backed a military-backed constitution.” BBC. May 11, 2022. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-36972396.

The Secretariat Office of the House Representative. Kan khao Chuea Sanoe Kotmai Khong Prachachon Phu Mi Sitthi Lueaktang Tam Ratthathammanun Haeng Ratcha anachak Thai B.E.2560 [Summary of the voter's law initiative, according to the 2017 Constitution of the Kingdom (B.E.2560)], February 23, 2022.

The Secretariat Office of the House Representative. Sarup Phon Kan Damnoen Ngankan Khaochue Sanoe Kotmai Tam Ratthathammanun Haeng Ratcha anachak Thai B.E.2550 [The result of the law initiative, according to the 2007 Constitution of the Kingdom (B.E.2550)], February 23, 2022.

The Secretariat Office of the House Representative. Sarup Phon Kan Damnoen Ngankan Khaochue Sanoe Kotmai Tam Ratthathammanun Haeng Ratcha anachak Thai B.E.2540 [Summary of the result of the law initiative, according to the 1997 Constitution of the Kingdom (B.E.2540)], February 23, 2022.

Wikipedia. “Direct Democracy.” Last Modified February 25, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Direct_democracy.

Wikipedia. “2007_Thai_constitutional_referendum.” Last Modified February 25, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2007_Thai_constitutional_referendum.

Wikipedia. “2016_Thai_constitutional_referendum.” Last Modified February 25, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2016_Thai_constitutional_referendum.

[1] The results from the addition of the scores of each type of popular vote studied (popular initiatives, referendums, plebiscites, and obligatory referendums). The maximum score of two results from ease of initiative and ease of approval. Each of these terms obtains a maximum value of one and works as a chain defined by its weakest link. The maximum possible overall DDPP is 8 (scale it to a 0-1 range for graphical purposes).

[2] Section 43, the 2017 Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand.

[3] Section 133, the 2017 Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand.

[4] Section 254, the 2017 Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand.

[5] Section 256, the 2017 Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand.

[6] Section 57 (2), the 2017 Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand.

[7] Section 57 (1), the 2017 Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand.

[8] Section 63 and 78, the 2017 Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand.

[9] Section 178, the 2017 Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand.

[10] Section 252 and 253, the 2017 Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand.

[11] Section 77, the 2017 Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand.

[12] The military junta that ruled Thailand between its 2014 Thai coup d'état on 22 May 2014 and 10 July 2019.

[13] Section 8 Initiative Process C.E. 2021.

[14] Section 113, the 2017 Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand.

■ Thawilwadee Bureekul is the director of the Research and Development Office at King Prajadhipok’s Institute (KPI) where she is involved in the planning, management, implementation, and coordination of the Institute’s research projects. In addition to her role at KPI, Dr. Bureekul is a professor at several universities in Thailand, including the Asian Institute of Technology, Thammasat University, Burapha University, Mahidol University, and Silpakorn University. She succeeded in proposing “Gender Responsive Budgeting” in the Thai Constitution and she was granted the “Woman of the Year 2018” award, and received the outstanding award on “Rights Projection and Strengthening Gender Equality” in the Year 2022 as a result.

■ Ratchawadee Sangmahamad is a senior academic of the Research and Development Office at King Prajadhipok’s Institute. Her research focuses on gender, citizenship, election studies, and conducting the quantitative research. She has published books as a co-author, such as Value Culture and Thermometer of Democracy, Thai Citizens: Democratic Civic Education, and many articles, and Thai Women and Elections: Opportunities for Equality.

■ Arithat Bunthueng is an Academic of the Research and Development Office at King Prajadhipok’s Institute. He graduated in public law with an interest in and worked on projects related to law and society, decentralization of local government, Indigenous peoples' rights and human rights.

■ Typeset by Juhyun Jun , Research Associate

For inquiries: 82 2 2277 1683 (ext. 204) | jhjun@eai.or.kr

Center for Democracy Cooperation

Asia Democracy Research Network

![[ADRN Working Paper] Horizontal Accountability in Asia: Country Cases (Final Report Ⅰ)](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/20240305162413775004648(1).jpg)

Working Paper

[ADRN Working Paper] Horizontal Accountability in Asia: Country Cases (Final Report Ⅰ)

Asia Democracy Research Network | 2022-05-27