Authoritarian legacies have shaped party politics and electoral instability in Asian democracies. The article on the determinants of electoral instability in 19 Asian democracies found that contained electoral competition during the pre-democratic period distorted the formation of free and fair electoral environments after democratic transition.[1] This briefing focuses on how different types of authoritarian regimes before democratic transition influence the development of democratic party systems after transition and over time.

This essay has implications for the current debate on the crisis of representative democracy in Asia. Although highly stabilized electorates may strengthen rather than reduce political polarization, past studies suggest that high levels of electoral volatility can be a major roadblock to democratic consolidation, programmatic representation, political accountability, and good governance.[2] Where volatility is so high that voters feel disillusioned with the existing system and become ambivalent about the “relative merits of the democratic status quo versus strong, decisive, albeit less democratic, leadership,”[3] such disillusionment and ambivalence may pave the way for the electoral success of illiberal politicians, such as Duterte of the Philippines, and the rise in support for anti-political-establishment parties.[4]

Overall Electoral Volatility in Asia, 1948-2017

Original data on all 154 elections in 19 Asian democracies, broadly defined as all democracies in the Asian continent, namely from the regions of East, Southeast, South and Central Asia, and the Middle East, since the end of WWII, were collected and analyzed. To determine which countries and which time periods to include, Polity scores that classify a political regime ranging from 6 to 10 as “democracy” were utilized.

Electoral volatility was measured using Pedersen’s index as it is commonly used in the political science literature and captures “the net change within the electoral party system resulting from individual vote transfers.”[5] Specifically, it is called total electoral volatility (TEV), as it is calculated by estimating the difference between the vote share of the ith party at a given election (t) and the vote share of the same ith party at the election immediately prior (t-1), whose absolute values are then summed up and divided by 2. Therefore, to measure electoral volatility meaningfully for all occasions, a country is required to hold two elections in a row under “democracy” status and without interruption.

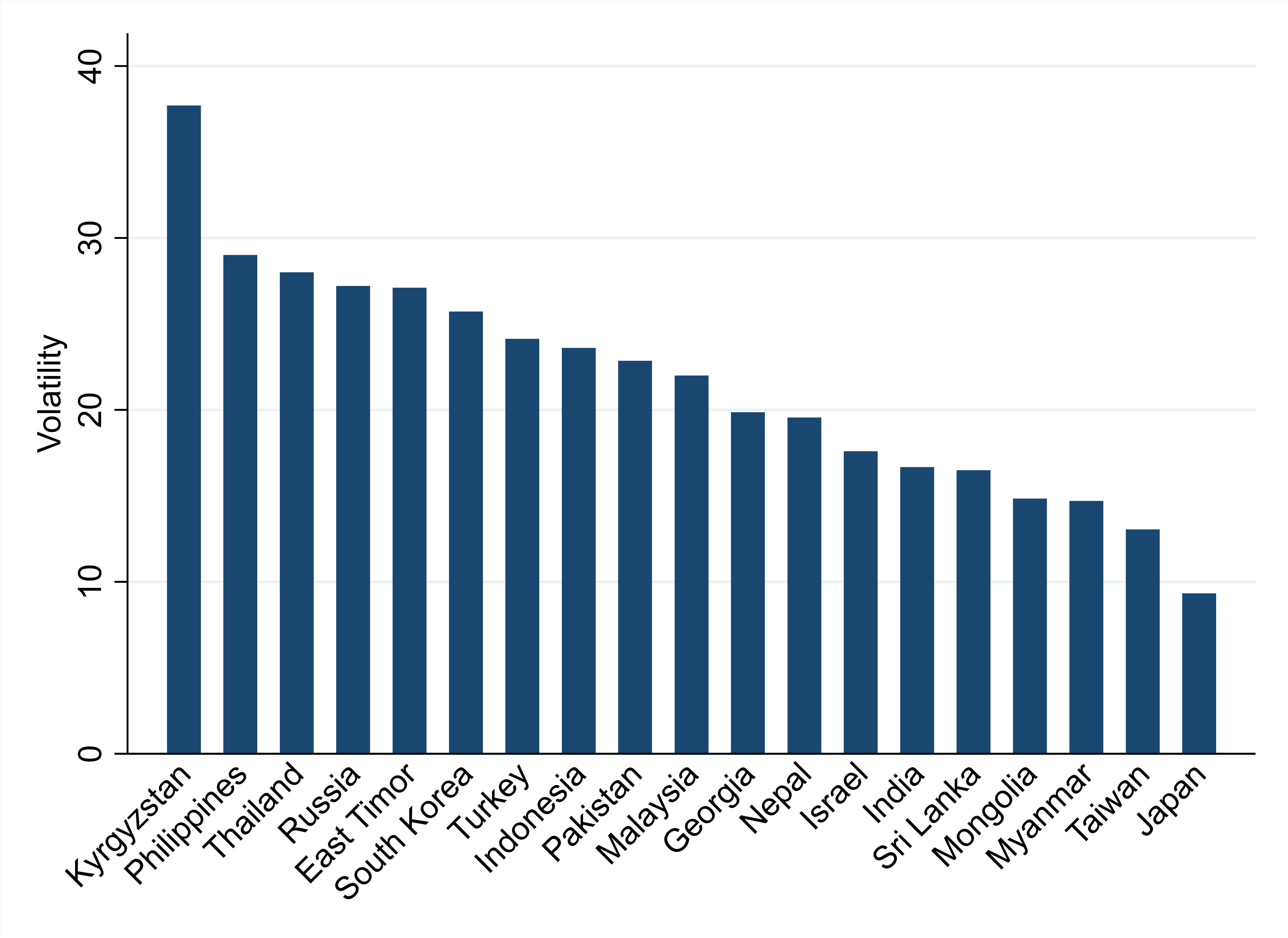

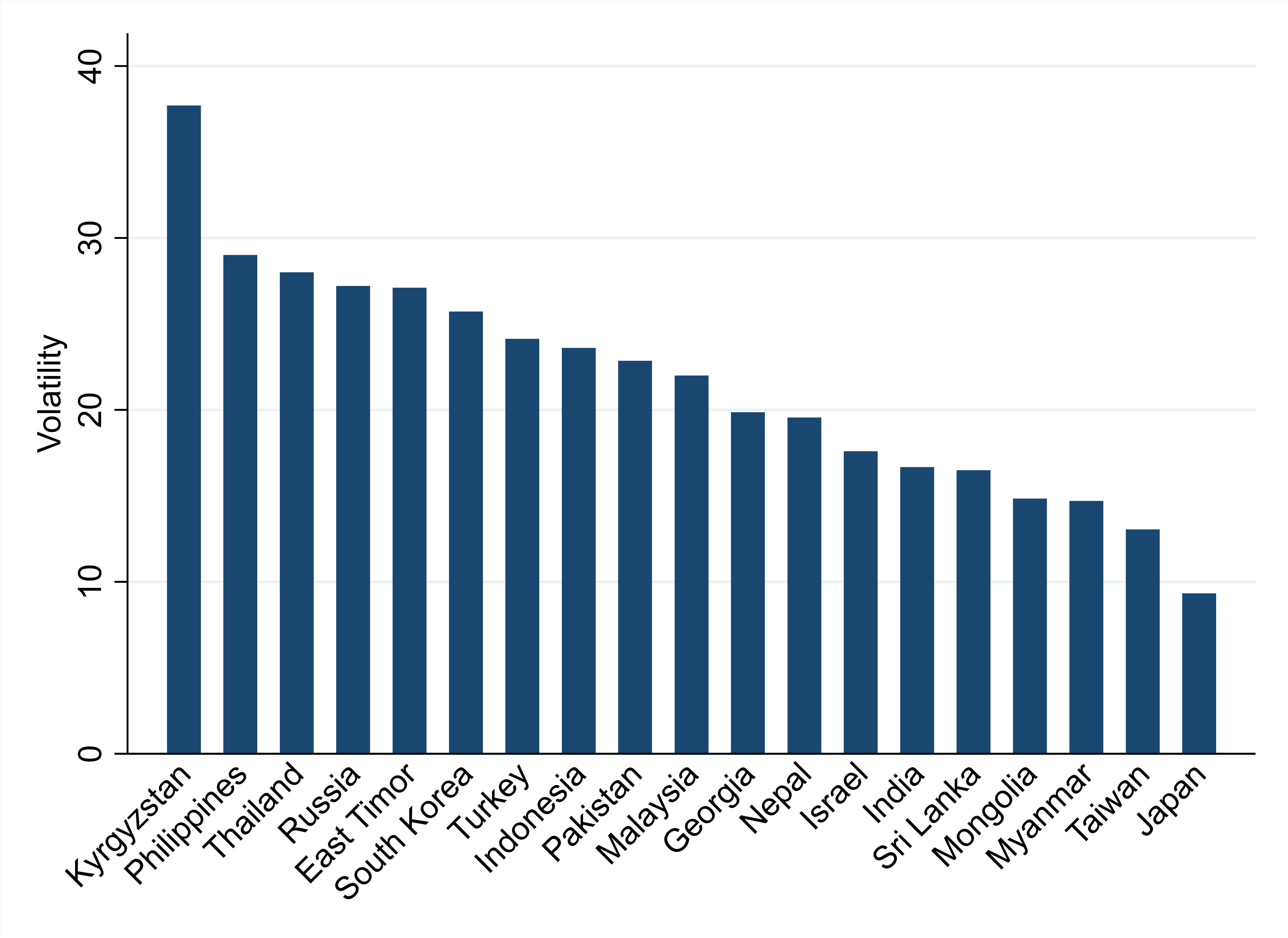

Figure 1 presents the mean volatility since the first democratic elections for 19 countries in Asia. The volatility scores range from 0 to 100 on a continuous scale, with higher scores indicating higher volatility. The average electoral volatility for the whole period in Asia is 18.7 percent. Compared with democracies in other regions, this is higher than the levels obtained in more consolidated Western European democracies but lower than those observed in other newly democratic regions, such as Latin America, Africa, and post-communist Europe. Yet, given that two-thirds of Asian democracies display an average level of 20 percent or higher, most countries in the continent seem to experience enduring systemic electoral instability.

Figure 1. Average Volatility Scores in Asia:

East, Southeast, South, Central Asia, and the Middle East

Source: Lee and Casal Bértoa (2021)

Further looking into the different sub-regions of Asia, no clear trend is visible thus far across East, Southeast, South and Central Asia, and the Middle East. Within the sub-regions, countries like Japan (East Asia), Israel (Middle East), Sri Lanka (South Asia), Georgia (Central Asia), and Myanmar (Southeast Asia) are all among the most electorally stable, while South Korea (East Asia), Turkey (Middle East), Pakistan (South Asia), Kyrgyzstan (Central Asia), and the Philippines (Southeast Asia) are located at the opposite end of the volatility spectrum.

Over time, however, with an exception of the three most consolidated democracies in the continent (i.e. India, Israel, and Japan) together with Indonesia and Taiwan, in the other continuous Asian democracies, namely East Timor, Malaysia, Mongolia, the Philippines, South Korea, and Turkey, electoral volatility scores have never been so low as during the current decade. [6]

Authoritarian Legacies as Determinants of Electoral Instability in Asia

In explaining what shapes electoral volatility in Asia, there are two clear reasons as to why the impact of authoritarian legacies is focused on in this study. First, while scholars have significantly contributed to understanding the causes of electoral volatility, they tend to focus on some common and conventional factors explaining electoral stability, such as political institutions and social cleavages, with a few exceptions of recent studies. Second, Asian democracies are ideal to examine the impact of authoritarian legacies, because, in contrast to other regions where all countries had an authoritarian past under military dictatorships, such as Latin America, or experienced the same type of legacy (e.g., communism in Eastern Europe, fascism in Southern Europe) before transition, Asia presents a rich variation in types of authoritarian legacies: communist (e.g., Mongolia), non-communist one-party state (e.g., Taiwan, Malaysia), military (e.g., South Korea, Thailand), personalist (e.g., Philippines, Nepal), and no legacy (e.g., Israel, India). Thus it is expected that this rich variation in authoritarian legacies will help to explain some variation of electoral volatility in Asia.

Recently, some Asian scholars have paid attention to the role of a country’s authoritarian past before democratic transition in shaping electoral stability after democratization.[7] With particular reference to some of the most highly institutionalized party systems in Asia – Taiwan and Malaysia – which have carried with them significant authoritarian legacies, the basic notion is that in these systems, hegemonic parties were dominant in the past. This helps to manage low levels of electoral volatility due to some constraints on competition. However, while contained electoral competition during the pre-democratic period may distort the formation of free and fair electoral environments after democratic transition takes place, this study argues that it may also be true that not all authoritarian regimes are the same.

That is, the detrimental impact of authoritarian legacies on democratic party system development depends on the degree to which they disrupt political development after transition. In countries where strong authoritarian parties existed, the same parties tend to re-emerge after transition because voters already have some attachment to them, and thus the level of electoral instability is expected to be lower. On the other hand, if parties were created by and strongly linked to authoritarian dictators, these artificially created parties to fall apart and electoral volatility is likely to be high after transition. Lastly, in countries where parties were non-existent or simply functioned as an electoral vehicle for military cliques, electoral instability is even higher as voters lack cues or attachment that will help them to make choices in a routinized manner. In sum, even after transition, the existence and re-emergence of hegemonic parties help the democratic system to manage low levels of electoral volatility. Although authoritarian interruption should undermine party system stabilization, certain types of authoritarian legacies were found to be less detrimental to electoral stability than other types.

Impact of the Three Types of Authoritarianism on Post-Transition Electoral Volatility

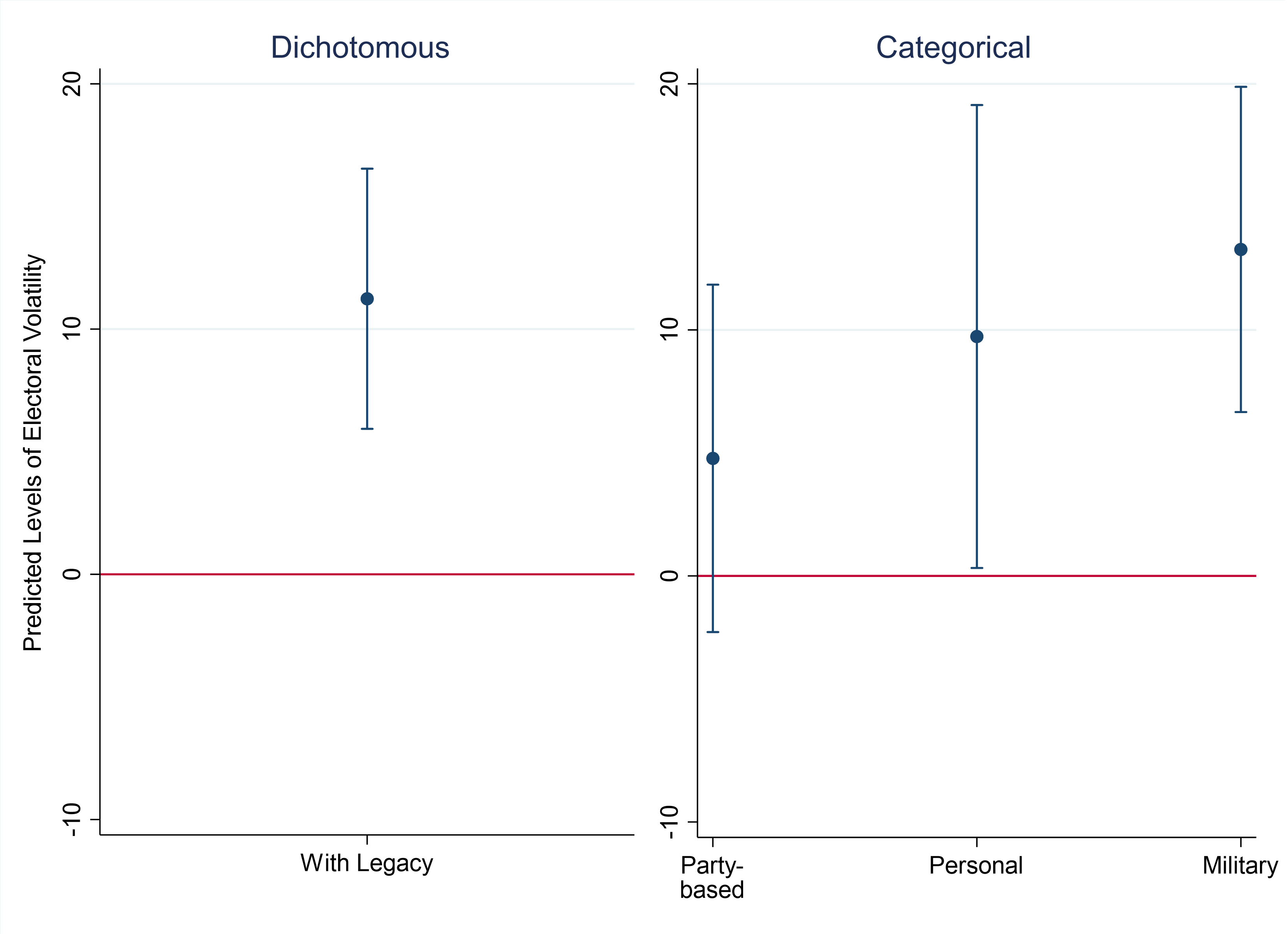

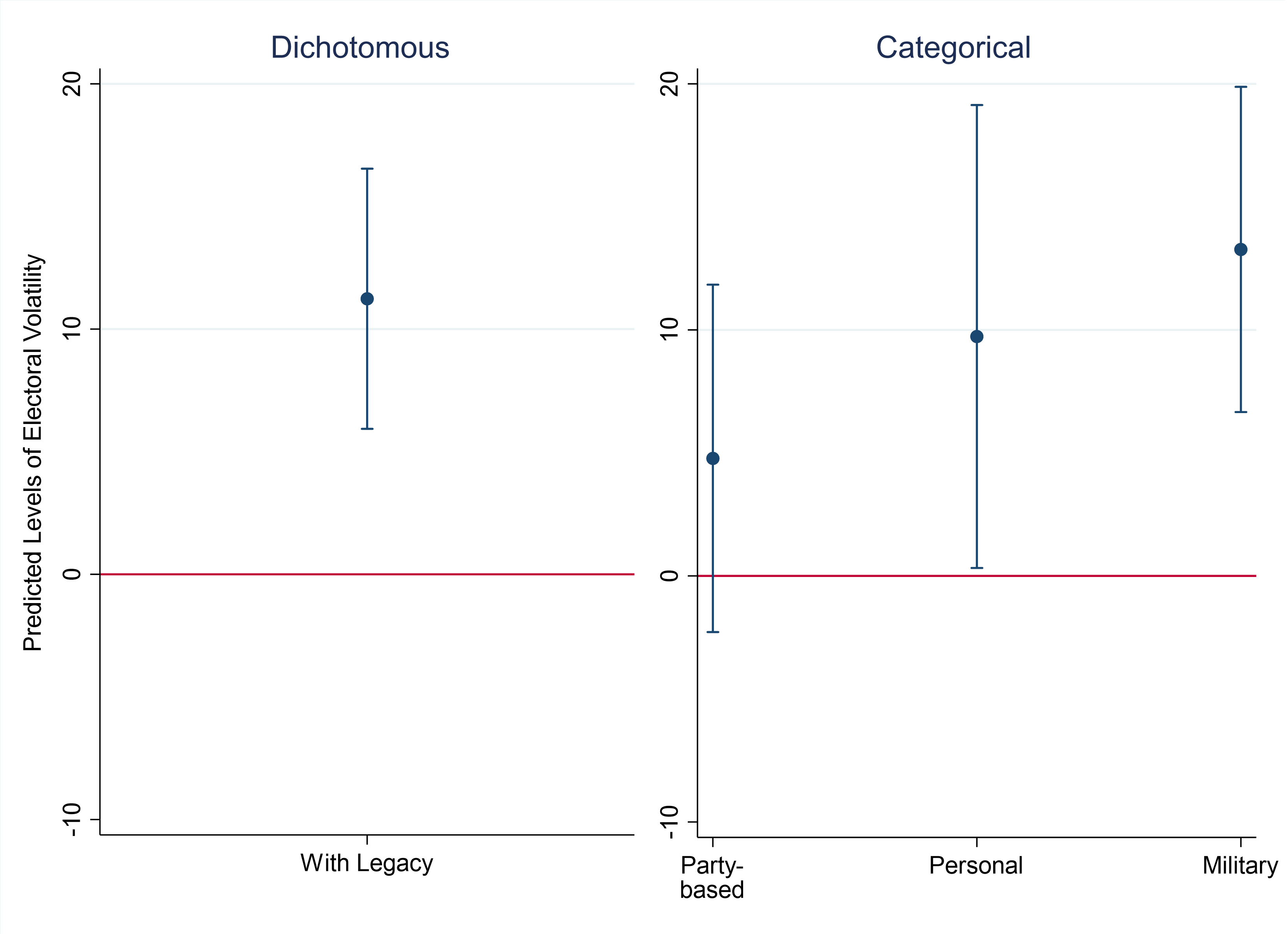

To estimate electoral volatility varying within and across countries, multivariate statistical models were employed to measure the impact of authoritarian legacies while controlling for various conventional factors proven in the literature to be influential. To present the results intuitively, the effect of authoritarian legacies in different measures after holding all other variables constant was graphically described.

Figure 2 presents two panels. The left panel shows an aggregate impact of pre-transition authoritarianism based on the multivariate analysis, and the right panel displays the effect of its legacy types based on the multivariate analysis. Figure 2 suggests that authoritarian legacies are indeed strong predictors for explaining electoral dynamics in Asian democracies and increase electoral instability in particular. For example, on the left panel, political systems with authoritarian legacies are characterized by 1.9 times higher volatility than those without such a legacy. On the other hand, the right panel shows that authoritarian legacies have a substantively significant as well as nuanced impact on political systems after transition: countries with military legacies show 85 percent higher volatility, while those with personalist authoritarian legacies display 58 percent higher volatility compared to countries without any authoritarian legacy. Countries with party-based authoritarian legacies also show 27 percent higher volatility than those without authoritarian interludes which is, however, not statistically significant.

Figure 2. Marginal Effects of Authoritarian Legacy in Different Measures

Notes: Estimation is based on the multivariate regression analysis. A baseline category is “no authoritarian legacy.”

In summary, as shown in the figure above, it can be observed that electoral volatility is lower in countries where political parties could participate in free (even if not always fair) elections or played a monopolistic ideological role (even if under authoritarian conditions — e.g., Japan, Taiwan, Malaysia) than in countries where they presented a functional (simply at the service of the particular dictator or military clique in power) and non-ideological character or they were simply inexistent (e.g., Kyrgyzstan, Philippines, Thailand). In the latter countries, electoral instability has become endemic.

Does this mean that countries with military or personalist authoritarian legacies are doomed to experience eternal instability? There is no way to change the past, but eventually, one can change the institutional design or introduce different economic policies that might help to stabilize electoral competition.

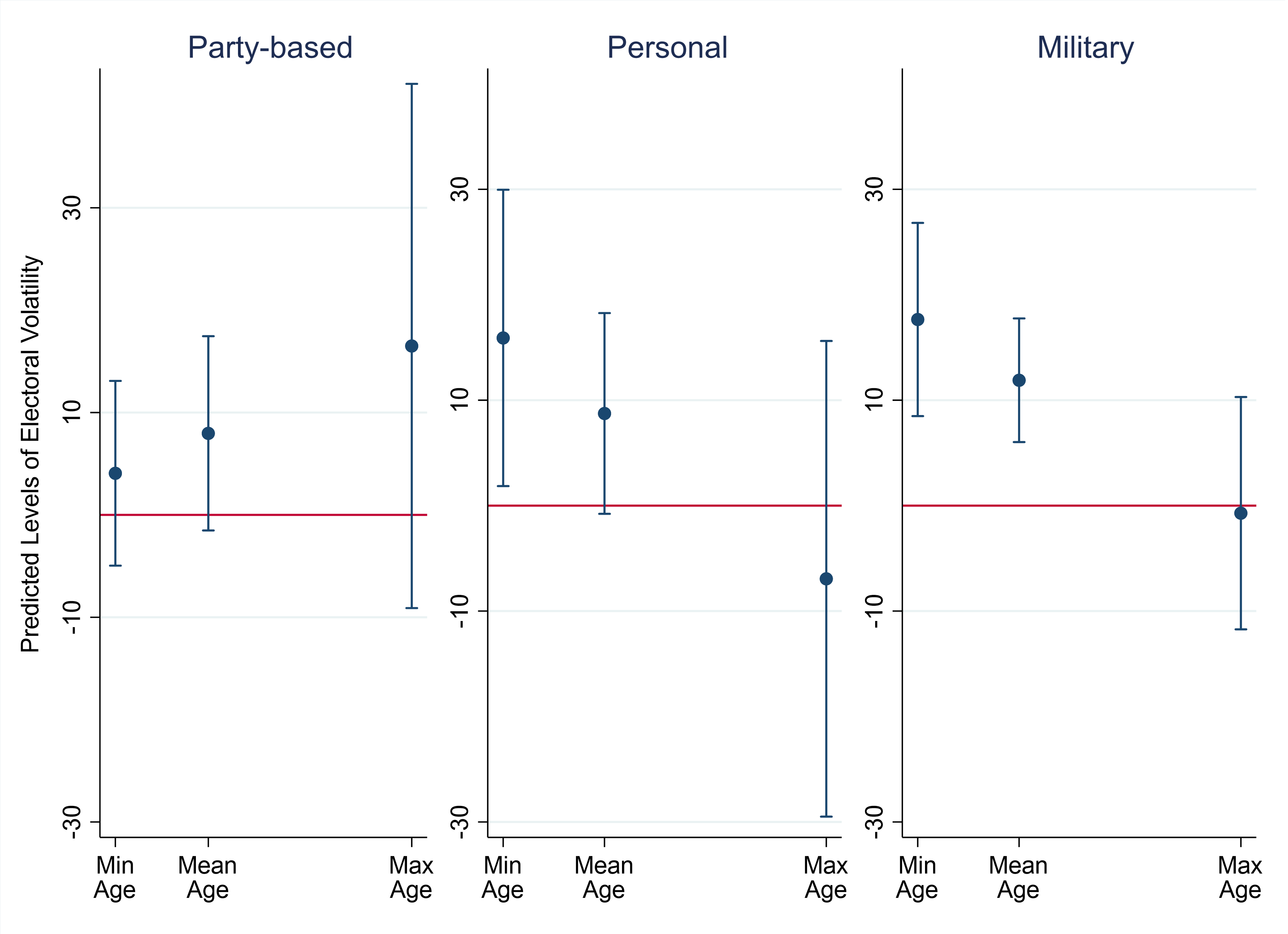

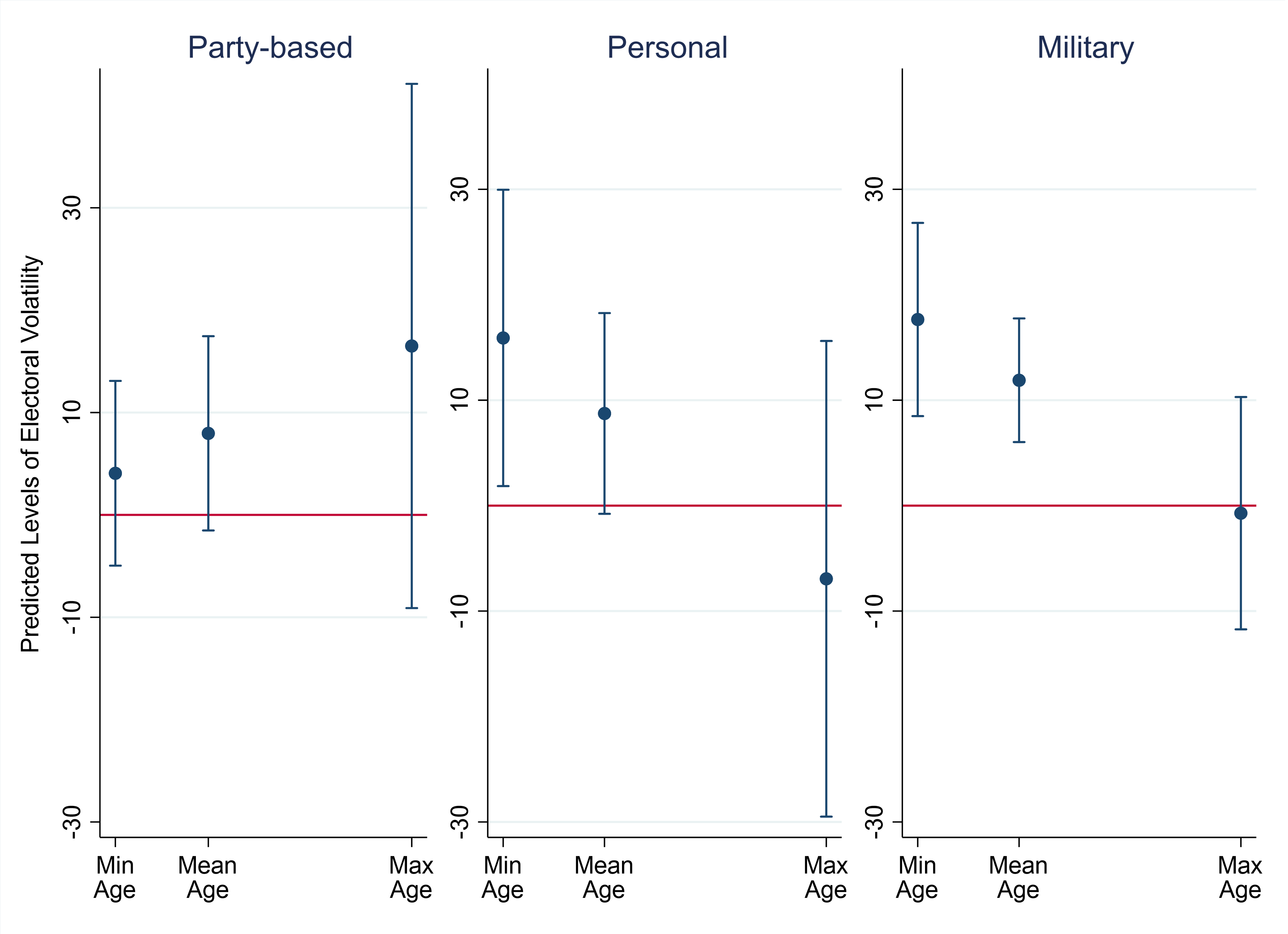

Impact of Authoritarian Legacies in Conjunction with Age of Democracy

Further to these findings, the effect of historical legacies in conjunction with time factors and the extent to which they are influential is examined. Taking into consideration that research on electoral volatility in Asia has emphasized the role of 1) the passage of time and 2) the characteristics of pre-transition regimes in shaping electoral dynamics and party systems,[8] the impact of the interplay between types of authoritarian legacies and age of democracy is further examined. To clearly illustrate how the nature of pre-transition regimes has long-run effects, co-varying with the maturation of democracy in reshaping electoral dynamics, graphical display is once again relied on. The power of this interaction effect is presented as plots in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Marginal Effects of Authoritarianism Type over Age of Democracy

Notes: Estimation is based on the multivariate regression analysis. A baseline category is “no authoritarian legacy.”

According to Figure 3, immediately after democratic transition (i.e. at the observed minimum “age of democracy” value), authoritarian legacies have significant effects on volatility, particularly for political systems with military or personalist legacies (2.8 and 2.6 times higher volatility, respectively, vis-à-vis those with no legacy). These effects still last but are less considerable after the passage of the observed mean “age of democracy” value (22 years). Compared to political systems with no authoritarian interlude, those with military legacies show 2 times higher volatility. However, with sufficient maturation of democracy (at the observed maximum value of 67 years), the difference in volatility between countries with no legacy and those with military legacies is no longer statistically significant.

All is not Lost but We Need to Earn It

The findings of this research indicate that there is hope behind the shadow of the authoritarian past, provided that post-transitional leaders manage to keep democracy as “the only game in town.”[9] This is because, following the analyses, it is possible for the routinization in political behavior generated by years of democratic experience to wash away even the worst authoritarian heritage. This is certainly good news for countries like Mongolia or East Timor which, despite years of authoritarianism, can expect a brighter (or more democratic) future. Consequently, by putting democracy at risk, political leaders in countries like India, the Philippines, and, most dramatically, Kyrgyzstan, might have re-started the clock, putting in peril not just democracy but the stabilization of party politics in the near future.

All in all, this analysis shows how history can be a millstone that determines the future of party politics and should not be tossed in the bin during political analysis. However, and more importantly, for the future of electoral politics and democracy in the region, political leaders — if willing to do so — can amend the mistakes of their fathers.

[1] This research is published in the academic journal previously. Don. S Lee and Fernando Casal Bertoa, “On the Causes of Electoral Volatility in Asia since 1948.” Party Politics, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/13540688211046858.

[2] For example, Mainwaring, Scott. 2018. Party Systems in Latin America: Institutionalization, Decay and Collapse. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[3] Hicken, Allen. 2015. "Party and party system institutionalization in the Philippines (324)." In Allen Hicken and Erik Martínez Kuhonta (eds.) Party System Institutionalization in Asia: Democracies, Autocracies and the Shadows of the Past. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[4] Casal Bértoa, Fernando and José Rama. 2020. “Party Decline or Social Transformation? Economic, Institutional and Sociological Change and the Rise of Anti-Political-Establishment Parties in Western Europe.” European Political Science Review 12, no. 4: 503-523.

[5] Pedersen, Mogens. 1979. “The Dynamics of European Party Systems: Changing Patterns of Electoral Volatility.” European Journal of Political Research 7, no. 1: 3.

[6] Casal Bértoa, Fernando. 2017. “Separation, Divorce or Harakiri? The ‘Crisis’ of Asian Democracies in Comparative Perspective.” Journal of Northeast Asian History 14, no. 2: 76.

[7] Hicken, Allen, and Erik Martínez Kuhonta (eds.). 2015. Party System Institutionalization in Asia: Democracies, Autocracies and the Shadows of the Past. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Linz, Juan J., and Alfred Stepan. 1996. Problems of democratic transition and consolidation: Southern Europe, South America, and post-communist Europe. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

■ Don S. Lee is an Assistant Professor in the School of Governance and the Department of Public Administration at Sungkyunkwan University (South Korea). Formerly, he held a position as an Assistant Professor and a Leverhulme Trust fellow at the University of Nottingham (United Kingdom). He has published 18 peer-reviewed articles on politics and public administration in Asia, including Comparative Political Studies, Governance, Journal of East Asian Studies, Party Politics, Policy & Politics, Political Research Quarterly, Public Administration, Public Administration Review, Public Management Review, and Regulation & Governance. His book, titled “The President’s Dilemma in Asia,” is under contract (Oxford University Press).

■ Fernando Casal Bértoa is an Associate Professor in the School of Politics and International Relations at the University of Nottingham (United Kingdom). He is co-director of REPRESENT: Research Centre for the Study of Parties and Democracy. Member of the OSCE/ODIHR “Core Group of Political Party Experts”, he is also an International IDEA and Westminster Foundation for Democracy collaborator as well as Venice Commission and United Nations expert. His latest monograph is titled Party System Closure: Party Alliances, Government Alternative, and Democracy in Europe (Oxford University Press, 2021).

■ Typeset by Jinkyung Baek Director of the Research Department

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 209) | j.baek@eai.or.kr

![[ADRN Issue Briefing] How Authoritarian Legacies Play a Role in Shaping Electoral Volatility in Asia](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/20220215112041399911425.png)

![[ADRN Issue Briefing] Decoding India’s 2024 National Elections](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/20240419123938102197065(1).jpg)

![[ADRN Issue Briefing] Inside the Summit for Democracy: What’s Next?](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/2024032815145548472837(1).jpg)