Weibo and “Iron Curtain 2.0” in China: Who Is Winning the Cat-and-Mouse Game?

Commentary·Issue Briefing | 2011-12-20

Jongpil Chung

Jongpil Chung is an assistant professor at the Department of Political Science, Kyung Hee University.

At the 2008 Chinese Internet Research Conference, Lokman Tsui, in his paper titled “The Great Firewall as Iron Curtain 2.0,” argued that the Great Firewall metaphor obscures and limits our understanding of Internet censorship in China. The term, combining “great wall” and “firewall,” is used to describe the Chinese government’s efforts to control the Internet while at the same time drawing on the Cold War term “iron curtain.” Yet the phrase “Great Firewall of China” gives outsiders the wrong impression, suggesting that in order to bring freedom of speech to the Chinese people, the wall should be pulled down to enable all good things, such as democracy, from the outside to get in.

The reality, however, is much more complicated. The Chinese Internet censorship system that filters or blocks external websites from internal view is only one part of a complex set of mechanisms. The Chinese government also uses cyber police and legal regulations to censor online content, and implements various types of surveillance and punitive actions to bring about self-censorship. Most entities in the private sector in China employ people to read and censor content manually, and can be warned or shut down by the Chinese government if they violate rules of acceptable content.

There are also Chinese blogs, emails, social networks, and text messaging services that have opened up new forums for exchanging ideas, and these have created new targets for censorship. Since China has never had mechanisms to accurately detect and reflect public opinion, blogs and BBS (bulletin board system) have become an effective route to form and communicate society’s public opinion. We should not underestimate the extensive consequences that the Internet has brought to every realm of global affairs. The Internet has enhanced the capabilities of traditional actors such as the state and firms, but these technologies have also empowered less privileged groups by providing information and facilitating participation in policy-making procedures.

The Internet and other networking technologies have facilitated change in the dynamic between the Beijing regime and the people in China. Who is winning the cat-and-mouse game? I argue that the Internet, more specifically Weibo (微博), the Chinese version of Twitter, and the microblogging system, have strengthened both the government and the people in China. Weibo has more functions than Twitter, such as commenting on others’ posts, turning a message into a conversation, and transmitting photographs and other files with posts. More recently, a great deal of politically sensitive material survives in the Chinese blogosphere provided by blog service providers such as Sina (新浪), Tencent (腾讯), Sohu (搜狐), and so on. The Chinese government is learning to adapt to these new circumstances, and becoming more responsive. Instead of strictly monitoring every posted comment on the Web, the Chinese government is selectively tolerating Internet expression “to provide a safety valve for the release of public anger” and improve its governance.

This article is organized into four sections: a debate concerning the political impact of the Internet in the context of Chinese state-society relations; an examination of how Chinese leaders censor the people’s use of the Internet and Weibo, and how their citizens use Weibo to gather information, exchange views, and organize protests and rallies; and a brief conclusion.

The Main Debate: Two Contending Perspectives

There are two opposing political views on the application of information technology in China: one sees the Internet and related technologies as allowing more opportunities for public participation, civic engagement, and strengthening the interaction between the people and government institutions in China, and the other views these technologies as allowing the Chinese government to control and regulate the Internet in whatever way it wants.

Guobin Yang has emphasized that the social uses of the Internet have fostered public debate and discussion of societal problems, and in the process have created a new associational form—the virtual community. The Internet has also introduced new elements into the dynamics of protest. Specifically, there is now a widespread belief in the policy world that advanced technology will pose an insurmountable threat to authoritarian regimes. Ronald Reagan’s speech at London’s Guildhall on June 14, 1989, was a good example of this view when he declared, “Technology will make it increasingly difficult for the state to control the information its people receive … The Goliath of totalitarianism will be brought down by the David of the microchip.” Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush were also staunch proponents of the idea that the Internet is inherently a force for democracy.

However, scholars like Lawrence Lessig argue that governments anywhere can most certainly regulate the Internet, both by controlling its underlying code and by shaping the legal environment in which it operates. According to Shanthi Kalathil and Taylor Boas, the Chinese state acts as a designer of Internet development and makes it less likely that non-state actors will have a political impact because Internet users “may back away from politically sensitive material on the web, and entrepreneurs may find it more profitable to cooperate with authorities than to challenge their censorship policies.”

Chinese Censorship 2.0

Several political bodies are in charge of Internet content in China, including most prominently the Central Propaganda Department, which ensures that media and cultural content follow the official line as mandated by the CPC and the State Council Information Office (SCIO), which oversees all websites that publish news, including the official sites of news organizations as well as independent sites that post news content. The Chinese government has adopted two main strategies to repress politically sensitive or “subversive” content online. First, the leaders use technical methods, cyber police, and legal regulations to screen online content. Second, the government implements various types of surveillance and punitive actions to boost self-censorship.

Using technology known as the “Great Firewall," the system blocks content by preventing Internet Protocol (IP) addresses from being routed through standard firewall and proxy servers at Internet gateways, blocks websites on an array of sensitive topics, while tens of thousands of government monitors and citizen volunteers regularly check blogs, chat forums, and even email to ensure nothing challenges the Party's propaganda. In China, Internet services are based on interconnecting networks, which are the national backbone networks that connect domestic Internet service providers (ISPs) to international networks. Since ISPs must obtain permission from one of the interconnecting networks to access global networks, they are under effective state control.

Chinese leaders have also been promoting self-censorship among the population as well as making the private sector, e.g. Internet Service Providers (ISPs), and owners of Internet cafes (wangba, literally, Net bar) more accountable for monitoring their customers’ emails and messages. To avoid being held legally liable for any inappropriate conduct, most Internet service and content providers prohibit users from seeing politically sensitive websites. Business owners use a combination of their own judgment and direct instructions from propaganda officials to determine what content to ban. The Chinese government imposes long prison sentences on scholars, journalists, and dissidents for expressing opinions that challenge the Party’s views or for leaking state secrets across borders. The strong punishment is especially aimed at preventing large-scale distribution of information that may lead to further collective action, especially off-line actions such as mass demonstrations or signature campaigns.

Although the political and social implication of the Internet depends largely on decisions made by leaders and policy makers in China, the Internet has facilitated the diffusion of power over information from the central bureaucracy to dissidents, students, and members of groups. The Internet allows the dissemination of information, especially through Weibo, to coordinate, organize, motivate, and transmit information with greater ease and rapidity than ever before. The following section will introduce the most popular and powerful medium, Weibo, that people use in China, and analyze the Wenzhou train crash case, where Weibo helped to disseminate information and organize protest events.

Creating Alternative Space: Weibo

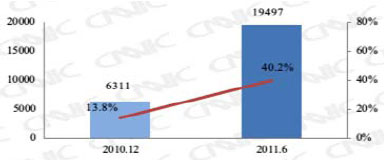

Although Twitter, the original microblog service, has been blocked in China, major websites have launched their own Twitter clones, and these have become important alternative channels for information. Microbloggers can publish messages, limited to 140 characters in length, conveying their thoughts, emotions, opinions, and what they see anytime, from any location, through cell phones or Web pages. Chinese mirobloggers show a strong interest in current affairs and form microblogger tribes through “follow” links, equivalent to a small-scale forum or platform of news and politics. These microbloggers, who are netizens, can cover sudden incidents live on the spot. In China, microblogging has been especially active since 2009, and users reached 194 million (see Figure 1) by July 2011.

Figure 1: Number of Weibo Users (Scale: 1,000)

Source: China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC), July 2011. http://www.199it.com/archives/2011071913139.html

Like BBSs, anyone with Internet access can start a blog on a hosting service with a very low cost of entry. Although most posts are personal in nature, more and more microbloggers are writing about public affairs and criticizing local government officials, particularly in relation to social justice, corruption, or people’s daily experience. One of the crucial impacts of this new technology is that negative reports and criticism of governments’ misbehavior are now being exposed and disseminated online. Sometimes such a process is tolerated by central authorities to keep local government officials more accountable to the center and to allow “the public to let off steam before it erupts uncontrollably, perhaps resulting in public protests.”

These emerging patterns of online interaction and communication underline how the Internet, more specifically microblogs, has expanded freedom of expression and broadened public discourse under the authoritarian regime. Citizens’ rising demands for greater freedom of expression, combined with new technologies, are challenging government control of information and media. Some popular microbloggers have large numbers of loyal followers and mobilize protests and petitions through the Internet.

Wenzhou Train Crash and Weibo

On July 23, 2011, two high-speed trains collided on a viaduct in the suburbs of Wenzhou, Zhejiang Province, China. Train number D3115 was struck by lightning near the town of Wenzhou on the Ningbo–Taizhou–Wenzhou rail line and then lost power and stopped while Train D301, running from Beijing south to Fuzhou on the same line, then rammed into the back of it. Six coaches derailed and four from D301 fell off the viaduct. Forty people were killed, and at least 200 were injured. Officials hastily pursued rescue operations, ordered the burial of the derailed cars and dead bodies, and issued directives to limit media and Internet coverage of this accident. The government’s reaction drew a great number of criticisms from online communities and media outlets, including defiance of officially sanctioned reporting rules on state-owned networks. Immediately after netizens’ criticism, China's State Council ordered a thorough investigation.

Since the accident, China’s two major Twitter-like microblogs, Sina (新浪微博) and Tencent Weibo (腾讯微博), have posted more than 26 million messages on the tragedy, including some that have forced embarrassed officials to change their previous decision to cover up what occurred. Although there were government censors assigned to monitor public opinion, most of the Weibo posts streaming onto the Web were unimpeded. The very nature of Weibo posts, which spread faster than censors can react, makes Weibo beyond easy control.

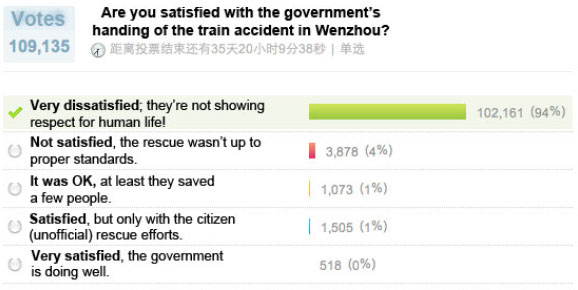

Within hours of the first report of the crash, comments and criticism were piling up, and over a week later, the flow of posts had barely slowed. There were more than ten million comments about the accident, nearly all of them extremely angry, and in user-created polls, netizens have again and again showed that they are angry with how the crash was handled by the government; in every poll, “very dissatisfied” has won with overwhelming numbers, and most of the polls have accrued tens and even hundreds of thousands of votes. According to a poll from Sina Weibo (see Figure 2), 94 percent of the respondents said they were “very dissatisfied since the government [was] not showing respect for human life,” and zero percent said they were “very satisfied.”

Figure 2: Are you satisfied with the government’s handling of the train accident in Wenzhou?

Source: Sina Weibo(新浪微博), July 24, 2011.

Like all domestic companies, Sina is required to censor content on its site, but the Wenzhou train crash incident has became too big for them to censor. Although deleting individual messages rarely works, it would be very dangerous and obvious to delete all messages about the accident, since by the time a censor finds the messages to delete, they have already been re-tweeted by dozens, hundreds, or thousands of others. In the case of the Wenzhou train crash, the Chinese government’s attempt to control reporting on the story was leaked onto Weibo, and provoked the already angered and dissatisfied Chinese people to ask for investigation of the case.

Conclusion

The Chinese government still imposes many restrictions on the Internet, both in terms of communication methods—for example, blogs or BBSs--and in terms of content--that is, what information is allowed on these open media. The recent “jasmine revolution” in China is one good example of what the party leaders are wondering about. On February 19, 2011, Chinese authorities suppressed online calls for a “jasmine revolution” and quickly dispersed small crowds that gathered in Beijing and Shanghai in an apparent attempt to spark an uprising similar to those roiling the Middle East and North Africa. Dozens of activists were detained, mass text messages were jammed and searches for the word “jasmine” were blocked on Chinese micro-blogging websites.

These events, however, do not mean that the Chinese government is winning the cat-and-mouse game. As we have seen, the Internet, and more specifically Weibo, is opening China to ideas and debates that have not generally been available through traditional media such as television, radio, and daily newspapers. By using Weibo, China’s citizens are becoming better informed about domestic and international affairs and are more easily mobilized. When "sensitive" information appears on Weibo, many netizens help to quickly republish and distribute it, often one step ahead of government censorship. Chinese leaders have realized that they must allow citizens some freedom online in order to prevent unexpected challenges to the CCP.

Weibo is helping more citizens to participate in public affairs and to demand more from their government. As Xiao Qiang, media scholar at the University of California at Berkeley, has argued, the Chinese government is starting to adapt to these new demands, as long as the demands are not related to sensitive issues such as Falun Gong, the Tiananmen Crisis, Tibet and Taiwan independence, or Liu Xiaobo, thus leading toward “the possibility of better governance and citizen participation.” Since early 2010, more and more party and government officials are opening Weibo accounts, trying to reach the public and maintain legitimacy through this new channel. However, this does not imply that the government leaders are ready to include Chinese people into the final decision-making process or make the process more transparent. The central government relies on the supervisory role of citizens on the Internet to exercise pressure on local government and state-owned enterprises’ corruption. By punishing the corrupted local bureaucrats or entrepreneurs, the central authorities will gain more support from the people and hold local officials more accountable to the center and to the public.

The major target in Hillary Clinton’s speech on “Internet Freedom” in January 2010 was China and other authoritarian countries facing strict censorship of the Internet. The point of the speech was that if the United States or any freedom-loving Western country can tear down the censorship wall in China and other authoritarian countries, then political change, and transition to democracy, will be greatly accelerated. Therefore, the State Department will financially help individuals silenced by oppressive governments and support “the development of new tools that enable citizens to exercise their rights of free expression by circumventing politically motivated censorship.”

As we have seen, the situation is much more complicated. In China, the Great Firewall is just one censoring system out of several, and most of the individuals are not silenced under the Chinese government. Chinese people are using the Internet and Weibo efficiently to deliver their complaints to the center or local officials and the government is gradually adapting to this new environment. Although there are certain limits in talking about sensitive issues, the development of the Internet and Weibo is mutually strengthening the state and society in China. Therefore, who is winning the cat-and-mouse game? Both are. ■

Acknowledgement

The author thanks Chaesung Chun and Minja Lee for helpful comments.

Center for China Studies

Rising China and New Civilization in the Asia-Pacific

![[ADRN Issue Briefing] Decoding India’s 2024 National Elections](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/20240419123938102197065(1).jpg)

Commentary·Issue Briefing

[ADRN Issue Briefing] Decoding India’s 2024 National Elections

Niranjan Sahoo | 2011-12-20

![[ADRN Issue Briefing] Inside the Summit for Democracy: What’s Next?](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/2024032815145548472837(1).jpg)

Commentary·Issue Briefing

[ADRN Issue Briefing] Inside the Summit for Democracy: What’s Next?

Ken Godfrey | 2011-12-20