Fellows Program on Peace, Governance, and Development in East Asia

Author

Gerald Chan is Professor of Politics and International Relations in the University of Auckland, New Zealand. He obtained his Ph.D in Chinese politics and history at Griffith University in Australia and his MA in International Relations at the University of Kent, U.K. Gerald has taught international relations and Asian politics for 15 years at Victoria University of Wellington. He has held visiting or short-term positions at many universities, including the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Cambridge University, the National University of Singapore, Nanyang Technologcal Universty, Singapore, and Kobe-Gakuin University in Japan. He is a Life Member of Clare Hall, Cambridge. He has been an external examiner to the politics programme at the University of Hong Kong. He also holds the position of an external Ph.D examiner in the area of Chinese international relations at the University of Malaya. He sits on the international editorial / advisory board of ten academic journals, including Global Society, Cambridge Review of International Affairs, the Journal of Human Security, and the International Journal of China Studies. Before he joined The University of Auckland in 2009, he was Professor of East Asian Politics and Director of the Centre for Contemporary Chinese Studies at Durham University, UK.

Professor Chan’s key research area is Chinese international relations. He has published a number of books and many articles in this area. He is currently working on several projects relating to China’s ability to create norms and rules that change the behaviour of other states; China’s role in global financial governace; and China’s aid policy.

Two of his co-authored articles won the Best Essay of the Year award: one entitled “Rethinking global governance: a China model in the making?”, in Contemporary Politics (2008); and the other entitled “Japan, the West and the whaling issue”, in Japan Forum (2005).

Abstract

China as a high-speed rail power has just begun to capture the attention of the world. The country now has the biggest high-speed rail network in the world, and it has started to export its rail products overseas. Yet there is little in-depth study of this curious phenomenon in the academic literature. This paper tries to fill this void. China’s global high-speed rail development is part and parcel of the country’s infrastructure diplomacy which, in turn, is a core part of its initiative to develop the New Silk Roads on land and at sea. The paper argues that the impact of such a mammoth enterprise on global development would be huge, in terms of geopolitics, geoeconomics, and social relations. It assesses Asian responses to this new diplomacy, especially those of Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan.

Keywords: China, East Asia, high-speed rail, infrastructure development, ‘one belt, one road’

Introduction

*This paper is a working paper (draft as of 31 January 2016). Comments and criticisms are most welcomed.

The central thesis of this paper argues that the development of China’s high-speed rail diplomacy (高铁外交) and the way in which China helps to finance this and other infrastructure projects will lead to the making of a ‘new’ world order. This thesis is new in several respects. First, China’s rise to become a high-speed rail power has occurred just in the last decade or so; the speed of development has been phenomenal. The country started to develop its high-speed rail system in 2004 by buying trains and rail technology from foreign companies such as Japan’s Kawasaki, Germany’s Siemens, France’s Alstom, and Canada’s Bombardier. Based on foreign technology and its experience in the train industry in the past, China began in 2007 to develop its own technology. On 1 August 2008 China’s first high-speed rail started to run between Beijing and Tianjin, a week before the official opening of the Beijing Olympic Games. In 2009 China decided to ‘go out’ to spread its high-speed rail investment, thus beginning a process of industrial transition from ‘made in China’ as a goods manufacturer to ‘created in China’ as a technology innovator and promotor. Three major lines are in plan to connect Asia and Europe, Central Asia, and Indo-China.

Second, China’s high-speed rail diplomacy has become the core of its infrastructure diplomacy which, in turn, has formed the core of China’s foreign policy, all happening within the last few years. Chinese Premier Li Keqiang has acquired the nickname of ‘China’s high-speed rail salesman’ as a result of his energetic promotion while on his many official visits around the world.

Third, to finance infrastructure projects under the New Silk Road initiative, China has taken the lead to set up the New (BRICS) Development Bank (in 2013), the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (2014), the Silk Road Fund (2015), and other funding mechanisms, both multilateral and bilateral. (See Appendix 1 for a chronology of the development of the ‘one belt, one road’ initiative). The initiative was proposed by Chinese President Xi Jinping in late 2013. It is known officially in full as the ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’ and the ‘21st Century Maritime Silk Road’ or in short the ‘one belt, one road’ or in Chinese yidai yilu (一带一路).

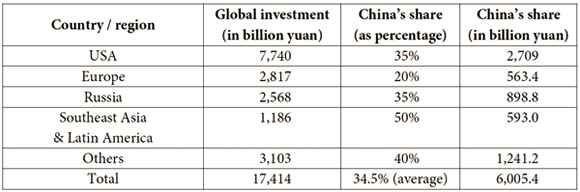

Fourth, according to the 21st Century Business Herald, a well-respected business newspaper in China, the global investment market in the time period 2014-2030 for high-speed rail industry is estimated to amount to 17,414 billion yuan, and China is going to take up the lion’s share of this market (see Table 1). At present, China is negotiating high-speed rail construction with some twenty to thirty countries. In 2014 China received orders for its train industry worth over US$100 billion.

Table 1. China’s share of the global market of high-speed rail industry, 2014-2030 (estimates)

Source: 21st Century Business Herald, 27 January 2015, p. 14.

Note: US$1 = 6.58 yuan (approx., as of 31 January 2016)

Theoretical Challenges

China’s ‘belt and road’ initiative has sowed the seeds for an emerging global order, one that is likely to challenge our understanding of international relations in four related areas: international development, international finance, international organisations, and ultimately peace and governance. In terms of international development, China, alone or with other emerging economies like those in the BRICS group (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), have forged a South-South cooperation programme that supplements the traditional type of aid extended by developed countries. This kind of South-South cooperation, in contrast to the traditional model, is based on mutual benefits among the parties involved, with infrastructure development as a main driver of economic growth. It does not set the kind of ‘good governance’ conditions, as do the World Bank and the IMF, which require aid-receiving countries to make major political and economic changes to their governance system. In this way, South-South cooperation can be seen to be competing with OECD countries for the hearts and minds of the people in the Global South.

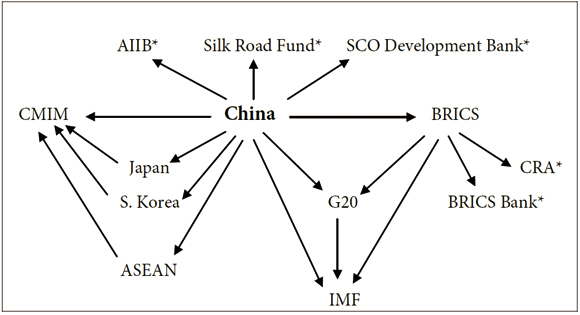

Figure 1. A model of China’s multilateral financial engagements

Direction of China’s desired flow of its influence

Direction of China’s desired flow of its influence

* These are new institutions initiated by China since 2013:

AIIB: Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank

CMIM: Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralisation

CRA: Contingency Reserve Arrangement

SCO (Shanghai Cooperation Organisation) Development Bank

Source: Author

Note: G20 holds 65.8% of the quotas of the IMF and 64.7% of its votes

In terms of international finance, China has played a leading role in launching the New Development Bank (or the BRICS bank, with an authorised capital of US$50 billion rising to $100 billion) with an affiliated Contingency Reserve Arrangement ($100 billion), the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank ($100 billion), the Silk Road Fund ($40 billion), and Shanghai Cooperation Organisation Development Bank (under construction), the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralisation ($240 billion). China has also set up other funding mechanisms, multilateral, bilateral, or commercial, as well as making contributions through its state-owned banks. (See Figure 1). These financial institutions supplement as well as challenge the work undertaken by the Bretton-Woods institutions, consisting of the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Trade Organisation, and by extension, the Asian Development Bank, the European Bank for Development and Reconstruction, and others.

In terms of international organisations, apart from the financial institutions mentioned above, China has played a major role in setting up the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, the Bo’ao Forum (China’s answer to the World Economic Forum or the Davos Forum), the Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia, the Xiangshan Forum (China’s answer to the Shangri-La Dialogue), and others. These organisations play a tune quite different from the traditional organisations set up and controlled by the West in managing global politics, finance and development. Also, there is an increasing number of Chinese nationals taking up senior executive and management positions in international organisations, although the number is relatively small and the increase very slow...(Continued)

※ This paper is a working paper (draft as of 31 January 2016). Comments and criticisms are most welcomed.