Jaewoo Choo is a professor of Chinese foreign policy at the department of Chinese studies, Kyung Hee University.

It is already a daunting challenge to predict Xi’s foreign policy stance and outlook for Xi has been in the office for less than a month. The article will attempt to read Xi’s foreign policy by making references to public remarks, statements, addresses, and records of talks by Xi and other members of the standing committee of the Politburo during the past couple of years. Contents analysis approach is possible for the availability of such documents to public. Furthermore, they are sufficient in quantity for Xi alone has travelled overseas for more than fifty occasions and received countless foreign visitors since his nomination as a successor to Hu in 2008. Of the seven members, Xi, Li Keqiang, a number two man in the standing, and Wang Qishan have also had chances to express their perception of the world, China’s changing international profile, and their own discourse on China’s foreign policy. Others while in the office at local level also have had chances to receive high-level foreign guests and travel abroad, but the scope and focus of their public talks do not expand beyond the local level.

The article will first discuss the historical implications of Xi’s ascendance to the leadership so as to saturate our curiosity and anxiety to learn early where and in what fashion Xi will lead his country in the foreign policy realm. Xi and his colleagues’ perception of the world affairs and China’s international profile will be inferred from their public statements. Based on this understanding the article will attempt to forecast what position Xi’s leadership will hold on some of the thorny issues to China’s national interests, ranging from US-China relations, territorial disputes in South China Sea and East China Sea, US-South Korean alliance in the context of containment, North Korea’s possible missile launch to Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), China-South Korean Free Trade Agreement (FTA) and China-South Korea-Japan trilateral FTA. In the last part of the article will conclude with some thoughts on South Korea’s policy to China and the challenges confronting South Korea.

Historical Importance of Xi’s Rise

Unlike in the past, has the world never been so anxious to learn early about the direction of a new Chinese leadership’s foreign policy. The unprecedented level of anxiety can be reasoned by the context of the occasion in Xi’s succession. The context of such occasion itself bears much significance to world politics as well as China’s own domestic politics.

From China’s own domestic political perspectives, Xi rose to the occasion in which China expects to be at a critical stage of its development. It is conceived to be a strategically critical opportunity, an opportunity that China must seize to achieve the second goal of China’s economic reforms and open door policy. That is, realizing a so-called “Xiaokang” society (an affluent society) in 2020. Granted his tenure to be two terms (2012-2022), Xi has the world of responsibility on his shoulder.

However, Xi’s ability to seize the occasion has been widely questioned by the alleged power struggles inflicted by one of the major political scandals in the history of People’s Republic of China (PRC). The subsequent purge of the son from the first general revolutionary family, Bo Xilai, and his clan only gave rise to the surmounting suspicion on Xi’s political basis within the party and his ability to seize power. Uncertainties seemed to have loomed larger than ever on the transition question, inviting skepticism on his relations with his predecessors who are supposedly to have much say in the formation of the collective leadership at the top.

From international perspectives, China’s global profile has made a quantum leap-like jump in recent times. China became a number two economic power in 2010, surpassing Japan. It has also successfully displayed its economic prowess following the global financial crisis in 2008, flexing its economic muscles in the right way by making significant contributions to the stability of world economy. In return, China was able to successfully garner more voting power stakes in the world financial institutions including the World Bank and IMF. Hence, regardless its likings, China is now often dubbed as one of the great powers or so-called “G-2” with the US.

Secondly, China’s rapid rise in the international profile also gave a drastic rise to the change in power configuration and therefore structure in East Asia. East Asian states are now conscientious of predominant regional actors, i.e., China and the US, in professing their foreign policy. Conversely, China is never been more challenged by America’s check and balance efforts in the foreign policy realm. Lastly but not least, it is largely because China and the US will have to resume the relationship and policies that were left off by the leadership change in both countries. The story is soon to be picked up where it was left - and it already has with Obama’s visit to Thailand, Cambodia, and Myanmar (November 17-20) immediately following his successful re-election. As both China and the US assert no significant change but continuity of the ‘current policy,’ it is most likely the US will continue its “pivot to Asia” policy as the cornerstone of Obama administration’s Asia policy, and China most likely continue to seek ways to defend its so-called ‘core interests’ in East Asia.

For the aforementioned reasons, the political succession in China at this particular juncture has drawn more attention from the world than ever. The second decade of the 21st century will be predicated on how China will conceive and respond to US pivot to Asia policy. Will China be immensely intimidated? Will it find ways to secure peace and stability and realize its national goal of becoming a xiaokang society or an affluent society? How will it manage its relations with the US for this end? These are some of the critical questions not only to China’s interest but also that of the world.

Some Propositions for Better Reading Xi’s Foreign Policy

Given the historical meanings of the leadership change in Beijing, the following propositions are offered for a better understanding on the prospective Chinese foreign policy in Xi Jinping’s era.

First, it is most likely that Xi will inherit the legacies of the fundamental framework and policy lines of his predecessors, and therefore, few changes are expected. Xi’s leadership will continue to view the theme of the current world affairs to be peace and development, while upholding long-held fundamental foreign policy principles including the five principles of co-existence, independent diplomacy, non-alliance, anti-hegemon diplomacy, and peace diplomacy. Newly adopted principles such as New Security Concept, peaceful development, and harmonious world will remain effective also. The backbone of China’s regional policy is to be good and friendly neighbor policy. However, in practice, Xi’s foreign policy in the first couple of years will be framed by the basic stance undertaken by Hu. In other words, Xi’s government will be persistent in seeking cooperation to realize mutual interests with others while stand adamantly against any foreign interference on the so-called China’s ‘core interests.’

Second, Xi will become much more fast moving with founding efforts on what I would term ‘uniquely Xi’s own feature of foreign policy.’ His group of leaders was reduced to seven members from what it used to nine for the past two decades for enhancing the effectiveness of collective decision-making process purposes. Moreover, all seven members share a similar world outlook and an attitude highly appreciative of China’s peaceful rise. Never the less, they are not hesitant in expressing displeasure against foreign criticisms and what they conceive as excessive demands, and are assertive and aggressive in fending them off.

Furthermore, Xi’s simultaneous succession of both Secretary-General of the party and Chairman of Central Military Commission (CMC), coupled with the pending presidency next year, will enable him to pursue his own foreign policy and strategy unlike his predecessors. In other words, Xi is better equipped with a greater room for maneuverability in making a foreign policy. Hu Jintao, for instance, on the other hand, was not able to deliver his own foreign policies (e.g. “peaceful development” and “harmonious world”) until it was confirmed he be transferred of the Chairmanship of the CMC from his predecessor, Jiang Zemin. Although Hu succeeded the party leadership in 2002, it was not until his succession to the CMC leadership was pronounced in 2004 that Hu finally was emancipated from the political shadows of his predecessor and became independent in pursuit of his own policy. It was then his government delivered successive foreign policies, one that contained the direction of the policy as in “Peaceful Development” and the other the goal, a “Harmonious World.”

Last but not least, continuity over changes in the foreign policy of the last government will prevail at least for the short term in Xi’s government because both China and the US is skeptic about one another’s strategic intentions of the policies that are to resume. While many expect the new leadership in China will have to focus on surmounting domestic challenges vis-à-vis the US, however, their argument on the likelihood of the rise of conflict between the two states is gaining grounds as few changes but continuity are conceived to follow as evidenced in recent Obama’s diplomatic maneuvers and Hu’s address at the transfer of power to Xi.

Although Hu emphasized China would be a more responsible state and make greater contribution within its capacity, he also firmly asserted on the needs to protect China’s core interests and so has the US Secretary of the State on fundamental interests of the US in Asia in recent times. Hence, it is most likely that they will remain unyielding and undodging to the pressure to compromise some of the strategically thorny issues such as currency devaluation, freedom of navigation issues in South and East China seas, and US resumption of pivoting in Asia policy. It is in large because these issues directly concern the fundamental strategic interests of both nations, so-called ‘core interests’ of China and ‘fundamental interest’ of the US. It would otherwise be a landmark achievement if they can compromise on any of them.

Xi’s Similar Perception but Different Approaches

Luckily for us, there are many documents we can refer to for our understanding of Xi and his colleagues’ perception of the world, China’s international profile, and Sino-US relations. Xi has travelled more than 50 times abroad since his designation as the successor in 2008. He also received many top foreign leaders in Beijing. There were also many occasions in which he would deliver public speeches, addresses, congratulatory remarks at world gatherings, and other occasions alike. From these references, we may be able to draw how China’s new collective leadership perceives the current world affairs including China’s position and relations with the US. In the same vein, we can detect what we can call some uniquely own of the new leadership and distinguish how it will be different from the past one.

The followings are some of the important features in the new collective leadership’s outlook of the world.

First, Xi, like his predecessors, sees the main theme of the world is peace and development. He will not deviate too much, however, two points are noteworthy. One is that Xi rather professes the other side of the ‘peace coin,’ i.e. security. Whereas Hu was prolific in advocating the importance and value of world peace to the world development, Xi takes a rather realistic approach in addressing the world peace problem in the context of security. Furthermore, in addition to inheriting the same world outlook, Xi elaborates the logic behind the causal relationship of security and development in his own fashion. Xi claims that security will be secured through development; security will be sought through equality, implying equality’s prerequisite status of security; security will be guaranteed through mutual trust; security will be guaranteed by cooperation; and security will be pursued by innovation, implying innovative approaches and measures in solving international conflicts. Such logic indicates that Xi may be more security-oriented in his outlook of the world than his predecessors.

Second, with respect to China’s international profile, Xi has a conception of China being one of the “great powers,” alas not in the same connation of a super power but rather a big power. Xi disclosed it during his meeting with Vice-President Baiden last February. It was the first time that a top Chinese leader to define China’s states as such. Xi has justified his conception on the basis of China’s past and future economic role. In the past five years, Xi explained, China has made a consistent contribution of more than 20% to the growth of world economy. In the next five years, Xi predicts, China will import more than 8 trillion US dollars of goods and make an annual overseas investment of 100 billion US dollars.

Thirdly, Xi does not at the same time forget to defend China’s long-held definition of its global status, i.e. the largest developing nation. His logic of argument rests upon the realistic aspect of Chinese economy that China’s ranking in the world’s GNP per capita standing is well beyond number ninety and there are still 150 million Chinese living under poverty, i.e. one US dollar per day of living expense. Fourthly, Xi recognizes that China is now an important prerequisite to peaceful solution of international conflicts.

Lastly, Xi calls for a new paradigm for China-US relations, i.e., so-called “New Type of Great Power Relations (Xinxing daguo guanxi).” Although the idea was originally presented by Hu during his visit to the US in January 2011, it had different connotation for it was rather out of concerns on peaceful rise of China. Xi, on the other hand, sees it as an effective means to accrue a greater respect for being one of the big powers from the US. It is inferred from his pronouncement that mutual respect is the profound basis on which the “new type of great powers relations” should be built upon. Xi further elaborates that such a new type of relations is predicated upon mutual respect of the two countries. Furthermore, such mutual respect demands both nations to be objective and rational in each other’s strategic intentions while respecting respective party’s interest and stipulating cooperation as the legitimate means to solve international conflicts.

What to Expect from Xi’s Leadership in 2013

(1) On China-US Relations

How will the relations work out between the US with a re-elected leader and China with a newly elected one?

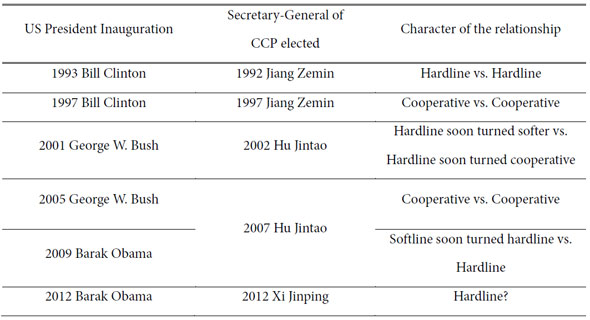

In the post-cold war era, and since China began to limit the office term of its top leader on five years, there’s not a case in which the leaders of the two nations were inducted into office roughly at the same time, only off by a couple of years in most cases as seen in [Table-1].

[Table 1] Chronology of the US and China Leaders Inauguration in the Post-Cold War Era

There seems a consistent pattern of cycle merging from changes of leadership and highs and lows in the relationship. In the first term of a newly formed government of both countries had a strong propensity to go about as hard as possible in their dealings with each other. Once they were re-elected, there seems to a great turnaround in their approach to each other, i.e. a much more accommodating, cooperative, and friendly one. Then a critical set of questions naturally arises: Will the pattern uphold for the second term Obama?; Will a newly elected leader of China pursue a much harder stance on the US?; Or will President Obama retreat to a more accommodating and cooperative stance on China from a hard line policy that he adopted in the second half of his first term?; Will Xi be rigid and inflexible as if to attest his grip on new leadership and power?

Xi and Obama both recognize the importance of cooperation and potential for mutuality aspect of the interests the two countries pursue in the bilateral relationship. Moreover, the two believe that as long as the relationship will be predicated on these common bases, convergence in their policy outlook can be facilitated. On the contrary, it seems that they are also highly aware of the underlying conflicts that could facilitate them to delineate from such cooperative stance.

The former perception lies in the following facts inferred from their perception of each other. First, China and the US highly recognize the value of cooperation as the basis of their constructive partnership. Both understand that without one the other cannot solve international problems confronting one or the world. Cooperation hence becomes the coupling medium of a relationship that has potential to evolve into a constructive one. Second, the relationship must be built on the notion of interworking. Constructive interworking of the bilateral relationship could advance mutual interests of the two nations. Already the trade volume of the two nations standing at 440 million US dollars, it reflects the economic structure of the two is complementary and mutually benefiting while mutually ‘win-win’ in nature. Hence, both recognize such mutuality facilitated by common interests can inherently advance towards more constructive way of development. Third, future relationship should fully reflect important historical lessons. History defines common interests as an inherent generator that advances the relationship forward, while the three joint statements that realized the normalization of the relationship is the institutional guarantor of the relationship’s development.

The latter recognition is manifested in some of the obvious different, yet controversial, outlook of the two nations in approaching East Asia and its order. First, the US, while placing a high value on cooperation with all regional states, still extends priority to cooperation with its allies. The US is, and will remain, persistent in its reliance on the allies as the means of preserving its predominance in the region. It will treat other regional members as an auxiliary yet complementary cooperation partner to promoting its strategic interests. China and Russia, for instance, are perceived to be so in Washington. Second, value-oriented approaches upheld by the US in its pursuit of multilateralism may strain cooperation with China and instead function as the cause of trouble for the two nations. The US is adamant with its insistence that the basis of regional order be founded on the values that it has consistently proclaimed, that is, market economy/free trade, democracy, liberty, and freedom. While the economic side of American value is well embraced by China, however, politico-social values are not. Lastly, US persistent demand of China to share more responsibilities for regional as well as world affairs is a source of conflict for the two nations.

While the two nations realize the criticality of cooperation by the two to effectively solve international conflicts, pressure on China to be more responsible in cooperating with the US will continue to be burdensome. US demand for further devaluation of Chinese currency Yuan, for instance, has been troubling and burdensome to decision-makers in Beijing. Others issues also, including the notion of freedom of navigation as advanced by the US in recent times, gave rise of conflicts in the area where cooperation between the two is highly sought.

(2) US Pivot to Asia Policy

China obviously is very much intimidated by the US determined efforts to continue in pursuing pivot to Asia policy. There is a growing perception in both Chinese government and military that it is designed to contain China, let alone engaging it. China on numerous occasions has already expressed its discomfort of America’s encroachment through relocating its military to the region as well as strengthening of its alliance system. Unlike the US, China only sees the military and security aspects of US pivot to Asia policy, nothing more or nothing less. It is therefore skeptical about US strategic intentions behind the policy. Xi’s government will share a similar, if not the same, perception on this particular matter. Hence, it will be defensive in its posture against America’s return effort to Asia as well as aggressive and assertive in defending its national interests including the core. As a result, it will be equipped with a never ending justification for its continuous efforts in modernizing its military forces, especially the navy and air forces.

(3) US-Japan-South Korea Alliance

As a part of America’s scheme of returning to Asia, Beijing is sensitive about the developments in US alliance in the region. Since 2010, it has been persistent in expressing its concerns on the strengthening of the alliance at the bilateral level. For instance, China once criticized US-South Korean alliance as a legacy of the Cold War and therefore the negative effect to the stability and peace in the region. It has also been overtly concerned with US response to Japan’s call of strengthening the alliance and expanding the scope and range of Japanese defense perimeter at the wake of territorial disputes over Senkaku Island (or Diaoyudao in Chinese) with China. Against this background, the US invited South Korea to join as an observer of the joint military exercise vis-à-vis with Japan, raising alarm in Beijing on the possibility as a founding cause of trilateral alliance. China has not been too explicit about South Korea’s participation in the US-Japan joint military exercises and Japan’s in the US-South Korea ones. It is, however, most likely that Xi’s government will not withhold itself in one way or the other. Considering their unrestrained way of expressing emotions and opinions on what they believe is unjust, unfair, and irrational, especially when it is related to the endeavors of foreign states, the new leaders will not hesitate to be vocal in delivering their concerns and dislikes. They will counteract in one way or the other, either by strengthening relations with traditional socialist states in the region or by aggressively modernizing China’s defense program.

(4) North Korea’s Missile Test

North Korea was allegedly ready to, and did on December 12, launch a missile test to commemorate the anniversary of the passing of the late leader Kim Jung-Il at the directive of his son and successor, Kim Jung-Eun. China has been quite proactive in taking the initiatives in communicating with Pyongyang, if not to dissuade it, to express its concerns on this issue. China has repeatedly stated that North Korea’s missile launch would be harmful to the peace and stability of the Korean peninsula, one of the ultimate goals in China’s Korean peninsula policy. To convey this concern, China has also dispatched an envoy following the party congress in November. It is doing so may be out of the concerns on the consequences of the North’s missile launch. Hence, it offered economic aid promise as a reward if the North were to show some restraint. International community and public opinion have been critical of North Korea’s planned action for its potent violation of the current UN sanction 1718. They have also been calling for more sanction to be placed upon the North’s missile launch. China at this stage is particularly not interested in seeing a challenge merging from its lone ally’s ignorance of warnings from the world. If North Korea were to carry out the missile launch as scheduled, it will significantly undermine China’s strategic position both at global and regional levels. It will be distasteful to China’s national interest. Hence, China has been compelled to take proactive actions to keep the North from launching the missile. In the end, it has expressed its disappointment but again demanded the world to show restraints as the UN Security Council was called upon to discuss a possible sanction. Insisting on no further sanctions necessary for there is already enough of it, Beijing will remain persistent with calls for talks and dialogue as solution, and perhaps oppose any more severe action on its lone ally. South Korean government, in collaboration with the world community, must seek ways to talk to China first and not North Korea as to what should be done if the North continues to violate the sanctions that it agreed following the North’s nuclear tests.

(5) North Korean Nuclear Problem and Resumption of the Six-Party Talks

China has been consistent with its efforts in calling for the resumption of the Six-party talks. In the recent discourse of the North Korean nuclear problem, both Hu and Xi have expressed the importance of the resumption of the talks to peacefully solve the problem on numerous occasions. Whether their statements have been mere rhetoric or not will have to remain for further observation with Xi’s government. Xi and his colleagues have emphasized the value of re-opening the talks even in unconditional terms. As long as Xi’s government will uphold and adhere to the principles of so-called “New Security Concept,” it will continue to seek opportunities to resume the talks for its firm belief in no better alternatives. It will be a daunting challenge to Xi’s government. If the new leadership will want to succeed, it will have to fulfill some critical diplomatic prerequisites. That is, China will have to be conflict-free in its relations with the concerned parties of the talks. However, at this particular moment, China’s external challenges alone will not be too serving to its own cause in pursuit of the six-party talks. China will enhance its efforts next year for it will be the 10th anniversary of the talks that is so meaningful to its multilateral diplomacy, however, it won’t be fruitful as long as it remains in conflict with the concerned parties over other externally challenging issues. At the end of the day, sanctions on North Korea will remain effective, if not furthered, for the foreseeable future unless China can induce it to the talks or create an environment conducive for the talks to hold at the cost of conceding much patience and tolerance against external challenges to its strategic interests, even the core interests.

(6) Territorial Disputes with Japan and Implications for Korea

China’s nationalistic stance on the territorial disputes against Japan will only stand pending on the next leadership in Japan. China has felt the mounting external pressure to not to aggravate the situation. America’s repetitive confirmation on its commitment to the alliance with Japan and warnings to China to restrain its action in recent times has successfully had a constraint effect on both China and Japan from direct physical confrontations. While the US has never been explicit about its position on the issue but the demand for a peaceful solution, it nevertheless remained firm with its warnings to both parties, repetitively demanding both to show restraints. At the same time, South Korea was experiencing political confrontations over its own territorial dispute with Japan, known as Dokdo (or Takeshima in Japanese) and China wanted to utilize it to its own advantage by expressing its sympathy to South Korea’s hard fought efforts against Japan. China also perceived South Korea’s isolation of Japan on international stages such as APEC of last September as an opportunity for collaboration to solve the origin of the problem, i.e. straightening of the distorted history by Japan. As manifested, China will facilitate the dispute for not only its own nationalistic interest but also for the alignment purposes against Japan. Nationalistic interests will extend to the enhancement of CCP’s legitimacy at times of difficulties. Alignment aspiration against Japan will be sought at any time if deemed necessary so as to garner support to the claim of its core interest. Hence, Xi’s government will most likely to manipulate the dispute whenever it rises to the occasion for the justification of uncompromising and unyielding nature of its core interest.

(7) China-South Korea Free Trade Agreement (FTA)

Xi’s leadership will highly likely want to conclude a free trade agreement with South Korea in the first term of office. The tenure of incoming president of South Korea will eclipse with Xi’s leadership for the next five years. Hence, if China persists with its efforts as it has with the resumption of the negotiation that was once called off, it realizes the prospect for the conclusion of FTA with South Korea can never be better. China’s aspiration for this end has been addressed in an explicit manner in the past. Xi and his colleagues have also expressed their desires during their visits to Seoul. On surface, they extol on the merits of a FTA with South Korea as mutually beneficial and winning to the cause of sustainable development of both countries. What will facilitate the FTA on China’s end is the strategic value embedded in the economic ties bounded by the agreement. As demonstrated in China’s precedent FTA cases, Beijing is not motivated by economic gains from FTA. Its counterparts, instead, are the economic beneficiary of FTA with China. Never the less, China has a strong interest in FTA for economic benefit reasons and political purposes. An affluent Chinese society will have a greater appetite for consumption and the government must saturate it at an affordable cost. At the same time, FTA can function as a strategic hedging tool by which Beijing can exercise greater leverage over heavily dependent states in political and diplomatic discourse. Although dependent states of China may not be an ally of China, they will have to take China factor into a serious consideration when making a strategic choice. Furthermore, as aggressive as China is in pursuit of a trilateral FTA with South Korea and Japan, a successful conclusion of a FTA with South Korea will offer China an upper hand in its negotiation with Japan. On the contrary, it could have an opposite political effect on Japan. It could further isolate Japan if it does not comply with China and South Korea’s aspiration for regional economic integration. Moreover, a FTA can offer China to occupy a niche in South Korea’s strategic calculation as well as in its alliance relationship with the US. It is feasible in part because 98% of South Korea’s GDP depends on trade revenue, and of the 98%, 24.2% ($220 billion) comes from the trade with China in 2011. A FTA with China in its strategic calculation will rise to a dilemma to South Korea’s alliance with the US. Hence, Beijing’s new leadership will be aggressive in its pursuit of FTA with South Korea in the foreseeable future.

(8) Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP)

Xi’s leadership will not be too concerned about the prospect of TPP becoming a regional economic entity with an isolation effect of China. Many American experts uses TPP to justify the non-military aspect of America’s pivot to Asia policy, often treating it as a political leeway in emphasizing the multi-dimensional perspective of the policy. China is, however, not enticed by the justification in large part because there has never been a regional case outskirt of the American continent in which the US succeeded in institutionalizing the regional economic integration process. At the global level, the US was effective in institutionalizing global financial institutions where global governance based on a global leadership was required At the regional level, however, the US has no successful stories but one that is geographically limited to its own perimeter, i.e. American continent. NAFTA, for instance, was merely driven by fundamental changes in US industrial structure and hence by sheer economic interests. In the same vein, neither is China much interested to be part of institutionalized regional multilateral establishments. While Beijing does not hesitate to take part in the institutions at global level, it has much reservation on those at the regional level, especially when they are against its principles of regionalism and multilateralism. These principles are based on the notion of ‘openness’ and ‘loose’ formation, implying a framework of institution that is not legally-binding and exclusive. Furthermore, another reason for China’s indifference is attributed to US persistent insistence that the multilateral institutions that it pursues must be value-oriented. Such orientation is not appealing to China and is conceivably designed to exclude it. However, even if China were to embrace the founding values designed by the US, there is not a case in which the US succeeded with institutionalization of such institutes with American values. APEC is the case in point and so are ARF and EAS in the non-military realm. Beijing therefore will not be too intimidated by the progress of TPP and it being excluded because already most of the members are heavily dependent on China.

Implications for South Korea’s Newly Elected Leader

Regardless of the party affiliation, the newly elected leader of South Korea will have to be prompt in reading the foreign policy stance of President Obama and Secretary-General Xi. As of now, many claim that there will not be too much change in President Obama’s East Asian policy but much continuity will prevail. Many Chinese constituencies of Xi also hold a similar view in their outlook of China’s policy towards East Asia in general and the Korean peninsula in particular for the next five years. They all based their argument on mounting domestic socio-economic problems confronting the two leaders. They claim that they will prevail in the policy order of priority over other issues including foreign affairs. To South Korea, however, all these claims and justifications could be misleading. They are misleading in a sense that no change will mean continuity of the policy with a great potential for conflict.

While the US persistent position on ‘no change’ will only demonstrate the prevalence of “Pivot to Asia” policy, and simultaneously, China will be adamant in defending its ‘core interests.’ Pivot to Asia policy prerequisites strong alliance in the region and will continue to push the US to seek ways to strengthen the alliance. Although the US also perceives one viable way to facilitate its strategic interests in the region is promoting multilateralism, however, it is a multilateralism dictated by American values. Composition of such multilateralism at this stage can only be made up of American allies and no one else. Whether China will be embraced in America’s regional architecture based on multilateral cooperation will remain to be seen. It will be also a daunting challenge to China if it will want to participate in American multilateralism largely because it is not ready to see its core interest agenda be handled at multilateral level or in the multilateralism context.

In the economic realm, the newly elected president of South Korea will also have to be aware the way Korea generates trade revenue. On the surface, China is South Korea’s largest export market. However, in reality, the final products that are assembled in China with South Korea’s exported parts and intermediary goods are destined to US market where hard currency of South Korea’s export are actually earned. Hence, such trade mechanism only enhances the value of US market to South Korea’s trade. Almost two-third (64.8%) of South Korea’s export to China are for process trade purposes, although China’s export dependency on process trade dropped from 57.4% in 2005 to 35.9% in 2011 as a result of a consistent turnaround efforts in the national economic policy to focus more on domestic consumption. However, South Korea’s market share in Chinese domestic market has remained in the low 30% at 34.1% in 2011. Furthermore, South Korea’s export market share for Chinese domestic consumption stands at mere 5.9% as of November 2012. Although most of the heavily dependent economies on China share a similar trade structure with South Korea, however, two states are exempted. They are the US and Japan and their Chinese domestic market share against stand at 66.7% and 51.7%, respectively. Thus, as long as South Korea’s China trade structure and share in Chinese domestic consumption do not drastically improve, South Korea will have to think hard on such economic issue as the devaluation of Chinese currency.

The foreign policy of South Korea’s newly formed government will have to be under great influence of the bilateral relationship outcomes between the US and China, especially at the early stage of the inauguration years. Hence, following policy suggestions are recommended: First, South Korea’s new government should emancipate itself from polarization in its thinking when comes to its relationship with the US and China, respectively. South Korea’s respective relations with the US and China is no longer played by ‘zero-sum’ game or relativity. South Korea can be free from this long-held perception by the realization that the alliance with the US is a fixed variable. The alliance with the US is not going to vanish overnight. Neither will it retreat to the extent that the efficacy of the alliance will not be felt at both global and regional level. Instead, it will perpetuate as long as the division in the Korean peninsula remains. Hence, there is no erosion in the relationship with the US because South Korea chooses to take a more cooperative stance on China. The US will always be with us. It is not going anywhere.

Conversely, there is no such notion as strengthening of alliance. We cannot be misled by any allegation on the strengthening of the alliance put forward by many pundits. Joint military exercises will continue to remain at the current scale and frequency if not drastically enhanced. Furthermore, there could be a rise in the number of formation for communication channels as witnessed in the recent establishment of “2+2” dialogue comprising of the foreign affairs and defense departments of the two nations respectively, however, it does not extend any military meanings beyond the sheer scale of military strength of the alliance.

Second, South Korea as a middle power should continue its efforts to found more multilateral cooperative channels. China is still a socialist state that holds different values, ideology, political system, social institutions and thus outlook of the world. As long as China remains so, it will be extremely difficult to expect it to embrace the values we cherish in the same context. The only viable way for China to embrace extensively of the values that the rest of East Asian countries all enjoy and respect is to induce it to a greater participation in multilateral establishments that are architected on such values. The more China participates in such multilateral framework, the more it will be acquainted with the values we all share and eventually will embrace them. It will take a lot of patience and hard thinking, however, with strong and proactive collaboration from the regional states, it is not impossible.

Last, South Korea’s newly formed government will have to be highly aware of China’s unswerving tradition ties with North Korea. Many South Korea media depicted Xi Jinping as one of the most knowledge leaders of South Korea, if not pro-South Korea, in comparative context. However, Xi is not the lone decision maker in a collective leadership like China’s. He will be subject to collective bargaining and decision making process. Although he will have the casting power at the final voting, however small or large such power will be, it is important to fully grasp the backgrounds and experiences that help formalize their perception of North Korea and the alliance at individual level if not at the collective one. Such approach is valid largely because a consensus formalized by an individual perception is most likely to converge into a collective one in case of North Korea. At least official statements from the top leadership in Beijing have proven otherwise.

Individual perception is usually formulated through two channels: One is through official visits and the other personal experiences. It has been the tradition since the third generation of the Chinese leadership that when a successor is designated, the first overseas trip arranged for the heir apparent is to Pyongyang. In a way, it is designed to equip him with an opportunity to gain a first-hand experience and understanding of the value of the alliance with North Korea. Xi, for instance, has a family background in his ties to North Korea. His father, Xi Zhongxun, a first generation revolutionary on par with Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping and Zhou Enlai, had a close personal relationship with Kim Il Sung. Xi Zhongxun was one of the Chinese delegates that received Kim at the train station upon arrival in Beijing. The tradition continued in 1983 when Kim Jong-Il made his first non-official visit to Beijing. Others also have had education experience in Pyongyang and extensive economic ties with North Korea in the past. Hence, South Korea’s new leader will have to be much smarter in talking inter-Korean relations and North Korean issue with his/her Chinese counterparts. ■

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank Chaesung Chun and Dong Ryul Lee for helpful comments.