1. Introduction

As the term "fake news" has degenerated into a pejorative phrase often used by politicians to criticize their detractors, the international community has shifted away from using it. Instead, the preferred term now is "disinformation." According to Merriam-Webster, disinformation is defined as "false information deliberately and often covertly spread (as by the planting of rumors) to influence public opinion or obscure the truth." This concept is explicitly distinguished from exaggerations or innocent errors. Notably, disinformation is not to be confused with hate speech or ridicule, which, despite their potential harm, are considered expressions protected under the umbrella of free speech. The key difference between disinformation and misinformation lies in the intent; disinformation involves an intention to mislead by disseminating fabricated images, videos, or unfounded arguments. The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) characterizes disinformation as “information that is false and deliberately created to harm a person, social group, organization, or country” (UNESCO 2018). Similarly, the European Union (EU) identifies disinformation as “false or misleading content that is spread with an intention to deceive or secure economic or political gain, and which may cause public harm” (European Commission). These definitions highlight a distinction from misinformation by emphasizing the intent to harm and deceive. However, discerning the intent proves challenging, leading to frequent indistinct use of the terms disinformation and misinformation. Within this framework, “fake news” constitutes a subset of disinformation, specifically pertaining to false news content. This study employs both terms—“fake news” and “disinformation”—interchangeably, reflecting their prevalent usage in South Korea, even within its legislative discourse.

Authoritarian regimes use disinformation as a tool to challenge the legitimacy of political opposition and to marginalize minority groups. In this regard, concepts such as “online freedom” and “internet freedom” emerge as safeguards against digital authoritarianism. According to Freedom House, online freedom has been diminishing for the last 13 years, with authoritarian regimes not only restricting access to social media and internet services but also engaging in the dissemination of false information or censorship through Generative AI. Reports indicate that 47 authoritarian states manipulate online discourse by generating artificial text, voices, and images, and 21 countries have mandated the integration of machine learning technologies on digital platforms to suppress political dissent and minority voices (Funk, Shahbaz, and Vesteinsson 2023).

Disinformation is also prevalent in democracies. Here, false information typically originates from a politically polarized populace rather than from state actors. Individual YouTubers or social media users, exploiting the democratic principle of free speech, may produce or share disinformation for financial gain or ideological propagation. This phenomenon is especially rife in societies marked by deep political divisions. Pertinently, even topics grounded in science, such as climate change and infectious diseases, are interpreted through the lens of political bias. Social media platforms, facilitating confirmation bias, exacerbate the spread of disinformation. Users who spread disinformation has two types of motivation. First is a true believer type. They are convinced that their views or faith is correct as a fact or righteous from a moral stand.. The other type is a partisan user.. They are motivated to support their political factions in environments of entrenched bipartisan conflict (Peterson and Iyengar 2021). Whichever the psychology is, disinformation thrives and proliferates when public opinion and social networks are divided. (Törnberg 2018). In other words, disinformation is amplified by the 'Echo Chamber' effect that transcends cohesive, like-minded groups to include broader networks sharing similar ideological stances.

Research on disinformation explores the influencing factors at both individual and societal levels. It has been observed that individuals with a high interest in politics or those who frequently use social media are more likely to spread disinformation (Morosoli et al. 2022). Studies focusing on social influences investigate structural factors that undermine democratic resilience through extreme ideologies. For example, societies dependent on alternative media sources, such as social media instead of traditional media, or those with populist political parties, are more susceptible to disinformation (Humprecht et al. 2023).

Meanwhile, democratic societies are more often the targets of foreign intervention aiming to manipulate public discussions, unlike authoritarian states which typically restrict information flow from abroad. Now, democratic societies try to curb down this disinformation infiltration. The discovery of Russian electoral interference in the 2020 U.S. presidential election prompted the United States to view foreign disinformation as a national security issue. Disinformation campaigns, such as those observed during the Russia-Ukraine War, are sometimes deployed in global public opinion wars. This has led many Western democracies to counter disinformation from authoritarian regimes like China and Russia within a security policy framework.

Election periods are particularly conducive to the spread of disinformation. This year, an unprecedented number of elections are taking place, with 83 countries—representing over half of the world's population—heading to the polls (Hsu et al. 2024/1/9). In response to this, platforms like Meta, YouTube, and X have reportedly ramped up their efforts to safeguard against election-related disinformation. In September 2023, UNESCO surveyed 8,000 voters worldwide (excluding South Koreans) to assess the impact of disinformation. The survey found that while 55% of respondents in developed countries rely on TV and 27% on social media for information, in developing countries with lower Human Development Index (HDI) scores, these figures shift to 37% for TV and 68% for social media. Nonetheless, concern over disinformation was universally high across countries of all development levels, with 85% of respondents worried about its effect on this year’s elections (UNESCO 2023). Similarly, in South Korea, disinformation is seen as a significant issue. According to a survey by EAI conducted in January 2024, 81.4% of Koreans recognized the seriousness of fake news, and 60% believed they were also susceptible to being misled by false information.

The UNESCO report revealed that in 16 countries, citizens believe that both governrnents (89%) and social media platforms (91%) should take strong action against disinformation or hate speech during election periods. However, regulating disinformation poses significant challenges. Identifying the individuals responsible for producing or spreading such information is difficult, leading to an emphasis on holding social media platforms accountable. Promoting media literacy education is also a common approach to empower internet users to discern and filter out disinformation themselves.

There also exists a significant cautionary voice against regulating disinformation. Critics argue that excessive regulation could hinder the flow of beneficial information and weaken support for democratization. Calls for more empirical data to assess the effectiveness of disinformation regulation as well as the justification for blocking disinformation efforts, and the argument that disinformation should be considered within the broader information ecosystern reflect this perspective (Wanless and Shapiro 2022; Green et al. 2023).

Balancing between addressing disinformation and avoiding the pitfalls of excessive regulation has emerged as a critical issue. This paper aims to contribute to the discourse by first exploring international regulatory trends, which could inform an appropriate regulatory approach for South Korea.

2. International Regulatory Developments

The 2020 report by the Broadband Commission for Sustainable Development, co-founded by UNESCO and the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), outlines the life cycle of online disinformation through five stages: Instigators, Agents, Messages, Intermediaries, and Targets/Interpreters (IAMIT). It suggests 11 strategic responses across four categories: 1) Identification Responses (monitoring and fact-checking responses, investigative responses), 2) Ecosystern Responses Aimed at Producers and Distributors (legislative, pre-legislative, and policy responses; national and international counter-disinformation campaigns; electoral-specific responses), 3) Responses within Production and Distribution (curatorial responses, technical/algorithmic responses, demonetization and advertising-linked responses), and 4) Responses Aimed at the Target Audiences of Disinformation Campaigns (normative and ethical responses, educational responses, empowerment and credibility labelling responses) (Broadband Commission 2020: 3).

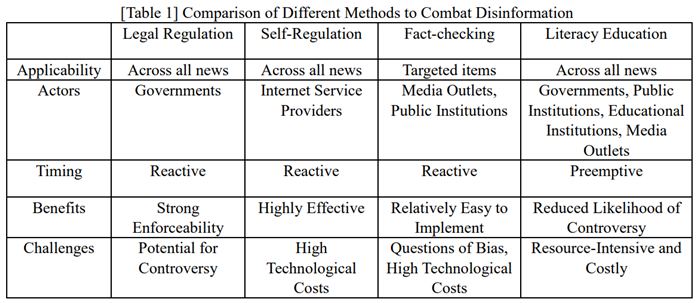

On the other hand, Jeong (2017) delves into the responding mechanisms to addressing disinformation,with four categories of legal regulations, self-regulations, fact-checking, and literacy education. He evaluates the applicability, actors involved, and the benefits and challenges of each approach, summarized in a comparative table.

Among these strategies, the U.S. and EU are increasingly focusing on legal and policy measures targeting the producers and distributors of disinformation. This approach stems from their mutual recognition that digital disinformation fuels political polarization, hampers pandemic response efforts, and heightens security risks and electoral interference from foreign actors like Russia. While Europe works on developing policies and legislation to balance freedom of speech with the need for disinformation regulation, the U.S. concentrates on establishing mechanisms within the executive branch for an early response to foreign-originated disinformation.

2.1 European Union

The European Union introduced the Digital Services Act (DSA) and the Digital Markets Act (DMA) in October 2022. The DSA is designed to protect basic rights and freedom of speech online, while the DMA focuses on fostering digital innovation, growth, and competitiveness within Europe's single market. By February 2024, EU member states were required to appoint a Digital Services Coordinator to facilitate policy coordination (European Commission).

The DSA was enacted to curb illegal and harmful online activities and to prevent the dissemination of false information. Its objective is to establish a transparent and equitable platform environment that safeguards users' security and fundamental rights. The DSA applies to online intermediaries and platform companies, including marketplaces, social networks, content-sharing platforms, and app stores. It seeks to recalibrate the relationship between users, platforms, and public authorities, positioning citizens at the center of its strategy (European Commission).

The European Commission outlines the DSA's key objectives for each stakeholder group. For citizens, it aims to enhance the protection of fundamental rights and children, increase control and choice, and minimize exposure to illegal content. For digital service providers, it offers legal clarity, a uniform set of rules across the EU, and support for start-ups and scale-ups. Business users of digital services are promised improved access to EU-wide markets and a more level playing field with illegal content providers. For society at large, the Act is intended to ensure greater democratic control over systernic platforms and address systernic risks like manipulation or disinformation.

The DSA categorizes online entities into four groups based on their role, size, and impact, imposing tailored obligations on each. "Very Large Online Platforms (VLOPs) and Search Engines (VLOSEs)" serve over 10% of the 450 million European consumers. "Online Platforms" include online marketplaces and social media platforms. "Hosting Services" cover cloud and web hosting services, while "Intermediary Services" encompass internet access providers and domain name registrars.

Particularly targeted are the VLOPs and VLOSEs, which must report user numbers by February 17, 2023, and provide updates every six months. Seventeen entities were designated as VLOPs and VLOSEs in April. Those whose monthly user average falls below 450 million are exempt. The governance role of Digital Services Coordinator kicks in on February 16, 2024, for the country housing the key offices of these platforms. For example, Alibaba (run by Alibaba Netherlands), with approximately 104 million European users monthly, places the Netherlands in the Coordinator role. Similarly, Google Ireland Ltd., overseeing Google Search and YouTube with 364 million and 417 million European users respectively, assigns Ireland the Coordinator role (European Commission).

Companies assigned as VLOPs and VLOSEs must comply with a set of new obligations within four months following their designation. First, they must enhance user empowerment by facilitating the reporting of illegal content and processing these reports promptly, creating a user-friendly environment, and ensuring transparency in displaying advertisements, content recommendations, and overall content management. Furthermore, these platforms are obligated to assess systern-specific risks and implement mitigation strategies, taking into account their societal impact. This includes addressing risks related to illegal content, freedom of speech, media freedom, pluralism, discrimination, consumer protection, fundamental rights (including children's rights), public safety, fair elections, gender-based violence, minors' protection, and mental and physical health.

Upon completing risk assessments and reporting them to the Commission for audit and oversight, the platforms must actively take steps to mitigate these risks. Additionally, VLOPs and VLOSEs are required to establish an independent compliance systern to monitor and minimize risks, conduct annual audit supervisions, share data with the Commission and EU governrnents for monitoring and assessment, grant researchers access to publicly available data, display advertisements not based on sensitive user data, and maintain a repository of all advertisements on their interface. Failure to comply with these regulations will result in a fine of 6% of their total global profits starting from February 17, 2024.

It is important to note that the DSA pertains only to illegal content and excludes harmful content such as blackmail, harassment, or hate speech. This distinction aims to prevent controversy over the definition of harmful content and protect free speech online. Instead, the EU is indirectly strengthening platform transparency and accountability to manage harmful but legal content. Calabrese highlights that the Online Safety Bill, currently under review by the UK parliament, faces challenges due to concerns over its potential impact on freedom of expression. Meanwhile, Hungary has enacted a law imposing up to five years of imprisonment for disseminating false information, a move seen as silencing governrnent critics and potentially contributing to democratic backsliding.

The DSA is anticipated to bolster the accountability of large platforms significantly. EU member states are tackling disinformation with national regulations. Countries like France and Germany have long-established laws against hate speech and election misinformation, with Austria, Bulgaria, Lithuania, Malta, Romania, and Spain introducing similar legislation.

2.2 United States

The United States has taken steps to establish mechanisms within the executive branch to combat disinformation. Particularly in response to the Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. Presidential election, it has enhanced its monitoring and surveillance systerns. In a bipartisan effort, the Congress passed the Countering Foreign Propaganda and Disinformation Act in 2017, which led to the establishment of the Global Engagement Center (GEC) within the Department of State. Subsequently, in the fall of 2017, the FBI launched the Foreign Influence Task Force, and the Department of Homeland Security introduced the Countering Foreign Influence and Interference Task Force in 2018, later adding the Disinformation Board in 2022. The Department of Defense also set up the Influence and Perception Management Office. The creation of similar groups across multiple agencies prompted calls for coordination and a unified strategy, leading to the establishment of the Foreign Malign Influence Center (FMIC) by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) in September 2022. The FMIC, aiming beyond just election security, addresses disinformation affecting general public opinion and supports the GEC's efforts at an intelligence level (Klippenstein 2023/5/5).[1]

The GEC primarily targets disinformation originating from Russia. A special GEC report, “Exporting Pro-Kremlin Disinformation: The Case of Nova Resistencia in Brazil,” illustrates how Russia manipulates information through both overt and covert networks to spread anti-democratic ideologies globally. This includes groups like the New Resistance (Nova Resistencia)[2], Fort Russ News (FRN), and the Center for Syncretic Studies (CSS), which, despite appearing as indigenous movements, are closely linked with Russian malign influence actors and promote neo-fascist ideologies. These efforts are part of Russia's broader strategy to destabilize democracies and support its geopolitical ambitions, such as the invasion of Ukraine (U.S. Department of State 2023/10/19). The New York Times highlights the GEC's proactive efforts to counter Kremlin disinformation before it becomes widespread, acknowledging the challenges of responding after dissemination (Myers 2023/10/16).

The U.S. approach to disinformation focuses on targeting networks with ties to foreign states, notably Russia, to address national security concerns. This has led to the creation of specialized units within various agencies to monitor, surveil, and counteract disinformation from specific countries. As South Korea observes an increase in disinformation from abroad and considering its tensions with North Korea, examining the U.S. strategy for insights into security-focused disinformation countermeasures could be beneficial.

3. South Korea’s Countermeasures against Disinformation

3.1 Recent moves

Several non-criminal, legal frameworks exist for addressing dissemination of false information, such as the Press Attribution Act and mechanisms for damage reparation. On the criminal side, sanctions include Defamation Offense and False Fact Publicity Offense under the Public Official Election Act. Recognizing that the diverse range of penalties complicates the fight against disinformation, there were two legislative proposals in 2018 aimed at amending laws on disinformation. Recently, with the increase in fake news targeting the President, prominent politicians, and public figures, there has been a growing movement to regulate such content, which was not previously subject to criminal penalties.

Thus far, internet news and articles published by established press companies have been governed by the Press Attribution Act. Lee Dong-Kwan, the former Chairman of the Korea Communications Commission (KCC), advocated for a “one strike out” law targeting media outlets spreading disinformation. The KCC announced plans to broaden the scope of communication reviews, including for internet news, and to update related legislation. In September 2023, the KCC established the “Task Force on Stamping out Fake News,” outlining a strategy for combating disinformation. This strategy involves forming a consultative body with the Korea Communications Standards Commission (KCSC) and both domestic and international portal/platform companies (e.g. Naver, Kakao, Google, Meta) to encourage self-regulation. The KSCS set to launch a reporting mechanism on its website (www.kocsc.or.kr) for the public to flag fake news, with a process for expedited review and requests for content modification or removal if necessary.

However, this regulatory push has faced opposition from the KCSC, the opposition party, as well as critical news outlets, which have voiced concerns over potential threats to media freedom and redundant regulations. Acknowledging these critiques, the KSCSC adjusted its approach by eliminating the distinction between swift and regular reviews, opting for a unified expedited process handled by its entire staff (Kang 2023/12/31). Since this adjustment, no further legal reforms have been pursued.

3.2 Legislative Efforts Against Fake News in the 20th National Assembly

During the 20th National Assembly's tenure (May 2016 to May 2020), there were 43 bills proposed concerning disinformation. These proposals included significant draft legislation such as the “Bill on the Establishment and Operation of the Fake News Countermeasures Committee,” the “Bill on Preventing the Circulation of Fake News,” and the “Bill on Activating Media Education,” with the remainder being amendments. Yet only the “Special Act on the Punishment of Sexual Violence Crimes” and the “Act on Promotion of Information and Communications Network Utilization and Information Protection,” both of which were amendments addressing issues related to deepfakes,were enacted (Kim 2020). Despite these efforts, the two main pieces of legislation aimed at comprehensively addressing disinformation, one proposed by the ruling party and the other by the opposition, were ultimately discarded as the assembly's term concluded.

Exploring the two bills proposed by both major political parties is insightful. On April 5, 2018, 29 lawmakers from the Democratic Party, led by MP Park Kwang-on, introduced the “Law on Preventing the Circulation of False Information.” This was followed by the “Law on the Establishment and Operation of the Fake News Countermeasures Committee,” put forward by 15 members of the opposing Liberty Korea Party, including MP Kang Hyo-sang, on May 9th.

The “Law on Preventing the Circulation of False Information” mandates that website users must not disseminate disinformation, and requires website managers to ensure such content is not distributed. This law delineates disinformation as information that: 1) has been identified as untrue by media outlets through a correction report in accordance with Article 12 of the Press Arbitration and Damage Remedies Act; 2) is determined to be false by the Press Arbitration Committee according to Article 7 of the same Act; 3) is judged to be untrue by a court; or 4) is subject to a removal request by the National Election Commission due to false fact publicity, regional or gender discrimination, or defamation. Essentially, in the South Korean context, “fake news” is defined as false information that is considered illegal under existing legislation.

KCC, the regulatory body responsible for this law's enforcement, outlines the necessity of creating a master plan to both inform about fake news content and prevent its spread. Website users are prohibited from disseminating false information that infringes on others' rights online. Individuals responsible for spreading such information face potential compensation obligations for any resulting damages and may be subject to penalties of up to 5 years in prison or fines not exceeding 50 million won.

Website managers are tasked with ensuring that fake news does not proliferate on their platforms. They must explore effective methods for processing removal requests from users and be aware that failure to implement preventative measures against the circulation of fake news could result in fines. If a user contests the website manager’s decision regarding their removal request, the KCC intervenes. In such cases, website managers are required to submit a report detailing their efforts to curb the spread of fake news.

On the other hand, Article 1 of the “Law on the Establishment and Operation of the Fake News Countermeasures Committee” sets its primary goal as laying the foundational elements necessary for the committee's establishment and operation, with the intention of safeguarding individuals' dignity and rights from the impact of false information. This legislation characterizes fake news as information that is either distorted or fabricated within information network systerns, newspapers, the internet, or broadcast news, specifically for political or economic gains. This definition implicitly aligns fake news with the concept of "any report on factual allegations of the press," as per Clause 15, Article 2 of the Act on Press Arbitration and Damage Remedies, thereby narrowing the definition of fake news compared to that proposed by the Democratic Party.

This legislation's core feature is the establishment of a "Fake News Countermeasures Committee" within the Prime Minister’s Office, aimed at fostering a comprehensive and systernatic approach to curbing the spread of disinformation. The committee is to be headed by a chairman and include approximately 30 members. This diverse membership comprises governrnent officials such as the Minister of Science and ICT, the Minister of Culture, Sports, and Tourism, and the Chairman of the KCC, the Press Arbitration Committee, and the KCSC. Additionally, it includes representatives recommended by 12 public organizations. including the Korean Bar Association, Korea News Association, and the Journalists Association of Korea, ensuring a broad spectrum of perspectives in tackling fake news.

Two key agencies tasked with combatting disinformation include: the Minister of Culture, Sports, and Tourism, responsible for implementing policies to prevent the spread of fake news on internet news services; and the Minister of Science and ICT, overseeing measures against disinformation on information services and broadcasting services. These ministries are required to present their strategies for curbing fake news in their respective areas to the Committee every three years. The Committee then integrates these strategies from various sectors to formulate a unified master plan. Unlike the law proposed by the Democratic Party, which focuses on the mechanics of fake news removal requests, handling objections to these requests, remedies for damages, and fines, this law envisages a model of horizontal cooperation and citizen participation through the adoption of a committee-based approach.

During the 20th National Assembly, there were additional amendments proposed to the Information and Communications Network Act aimed at addressing disinformation. The Liberty Korea Party introduced amendments requiring portals and service providers to actively monitor the circulation of fake news. These amendments stipulated prison sentences of up to 7 years for disseminating false information and up to 5 years for failing to adequately monitor such content. In the subsequent 21st National Assembly, the Democratic Party advocated for an amendment to the Press Arbitration Act in 2021, obligating the press to pay punitive damages of up to five times the actual damage caused by the dissemination of fake news. The People Power Party criticized this move, labeling it as an attempt to silence the press from making constructive criticisms of the governrnent.

Every attempt to draft or amend legislation targeting disinformation has sparked controversy and ultimately failed. The opposition party has often contested the ruling party's proposals, arguing that they serve political purposes or undermine freedom of speech. When roles between the ruling and opposition parties have reversed, their arguments have similarly flipped. Additionally, civil society organizations have consistently opposed regulatory efforts to tackle disinformation, irrespective of which party was in charge.

3.3 Legislative Challenges in Addressing Disinformation

These experiences underscore three principal challenges in legislating against disinformation: Firstly, the political framing of disinformation countermeasures renders consensus unreachable. The opposition party typically contests the ruling party's initiatives, alleging political motives, and positions flip when power changes hands. This partisan dynamic complicates achieving political agreement, derailing legislative efforts. Civil society, while acknowledging the harms of fake news, often resists regulation, fearing it may infringe on freedoms of speech and the press through potential overregulation.

Secondly, legal controversies add to the difficulty of enacting legislation. Overregulation, particularly in the form of criminal sanctions, risks violating press and publication freedoms protected by the Constitution. The ambiguity of offenses in the False Fact Publicity Offense and the potential for the Defamation Offense under the Public Official Election Act to contravene the principle of excessive prohibition—effectively annulling election results due to stringent minimum penalties—highlight the complexity. Choi (2002) suggests that both existing criminal penalties and new legislative efforts need refinement to balance press and publication freedoms with constitutional values like personal rights, social order, and national security.

Thirdly, the implementation of new disinformation laws poses its own set of challenges. Public agencies often lack the resources or technology to track and manage the spread of false information by social media users effectively. This has led to a preference for public-private collaborations or encouraging platform companies to enhance their disinformation filtering responsibilities.

However, a January 2024 survey by EAI revealed that 37.2% of respondents encountered online fake news related to elections or domestic politics, purportedly disseminated by foreign actors. This indicates that international disinformation is a growing concern for South Korea. The following section delves into public opinion on disinformation.

4. EAI Survey: Public Opinion on Disinformation Regulation

The findings from the EAI's January 2024 survey provide insightful data that could inform policy decisions aimed at combating disinformation. The key results are as follows:

Similar to perceptions in other countries, around 80% of South Koreans consider fake news a significant issue, with half reporting personal encounters with it. When the EAI survey asked if the participants had encountered what they believed to be fake news in the last 6 months, 44.6% responded affirmatively, 9% lower than the 55.4% who said "No." Meanwhile, the "Social Media Users in 2021" report by the Korea Press Foundation found that 77.2% of participants had come across news they deemed fake or false on their social media platforms. Whether this discrepancy between the EAI and KPF findings is caused by the specified timeframe of "last 6 months" in the EAI survey remains uncertain.

Among South Koreans who have personally experienced fake news, 68.0% reported finding it on the internet, particularly through portal websites, Facebook, and Kakao. The primary reasons they identified news as fake included its inconsistency with their existing knowledge or truth (65.3%), unclear sources (43.2%), and significant differences from other sources (33.2%). Less influential factors were overwhelmingly negative reactions from other users (6.3%) and unusually high view counts (4.5%).

Despite encountering fake news, responses tended to be more passive than active; 48.2% did little in response, 32.5% blocked the account, 25.3% alerted others to the falsehood, and 16.8% reported the account. Thus, passive responses, such as inaction or blocking the source, were about twice as common as proactive measures like informing others or reporting the misinformation.

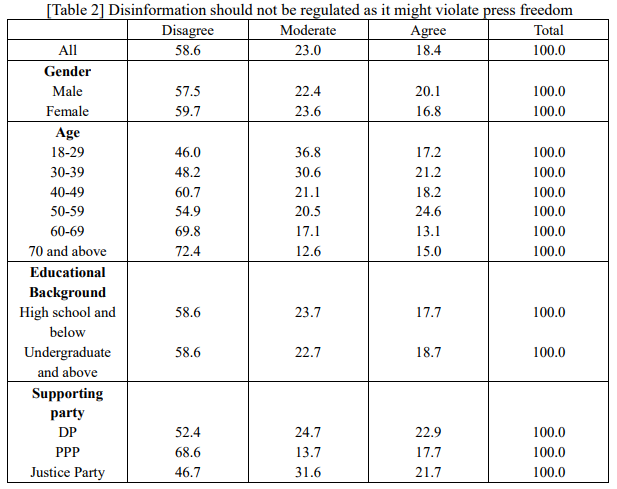

What does public opinion say about regulating disinformation? Firstly, the sentiment that disinformation should be penalized was more common than advocating caution to preserve press freedom. This inclination towards punitive measures increased with age. Only 18.4% of respondents agreed with the statement, “While disinformation is a problem, it should not be regulated because such measures might violate press freedom,” whereas 58.6% disagreed (23% remained neutral, not aligning with either viewpoint). In essence, the support for regulation was roughly three times stronger than opposition to it. Age-wise, individuals aged 40 and above tended to view regulation as necessary, whereas younger demographics, particularly those in their 20s and 30s, showed relatively less support for it (with 46.0% of those aged 18-29, 48.2% in their 30s, 54.9% in their 50s, 69.8% in their 60s, and 72.4% of those over 70 recognizing the need for regulation).

Secondly, the opinions on the responsibility for spreading disinformation among politically polarized YouTubers, politicians, and media uncovered partisanship and generational differences. Generally, YouTubers were deemed more responsible than either media or politicians. Respondents were given a scale from "Not responsible at all" to "Very responsible," with intermediate options. The aggregation of "Slightly Responsible" and "Very Responsible" responses yielded similar figures for conservative (67.9%) and progressive (65%) YouTubers. Age-wise, conservative YouTubers were viewed as more responsible by those in their 40s and 50s, while progressive YouTubers were deemed so by those in their 60s and 70s. Among Democratic Party (DP) supporters, 81.4% held conservative YouTubers responsible, in contrast to 50.9% of People Power Party (PPP) supporters. Conversely, 82.2% of PPP supporters blamed progressive YouTubers, compared to 46.1% of DP supporters.

For politicians from the ruling and opposition parties, the percentage attributing responsibility was close, at 53.1% and 54.8%, respectively. However, younger (18-29) and older (over 70) age groups tended to assign less responsibility to ruling party politicians, with similar patterns observed for opposition party politicians among those aged 18-29 and in their 50s. Party affiliation significantly influenced perceptions of responsibility; 69.6% of DP supporters found ruling party politicians responsible, compared to only 32.6% of PPP supporters. For opposition party politicians, 73.3% of PPP supporters acknowledged their responsibility, whereas only 35.6% of DP supporters did.

Regarding media, 56.4% attributed responsibility to conservative outlets and 55.4% to progressive ones for spreading fake news, with responses varying by age. Over 60% of middle-aged respondents blamed conservative media, but this dropped to 51.8% among those in their 60s and 44.4% in their 70s. For progressive media, around 67-68% of individuals in their 60s assigned responsibility, versus about half of middle-aged participants and 44.1% of the 18-29 age group. Ideological divides were also stark in media perceptions—74.6% of DP supporters accused conservative media of responsibility, while only 34.8% of PPP supporters agreed. Conversely, 77.9% of PPP supporters blamed progressive media, compared to just 35.3% of DP supporters.

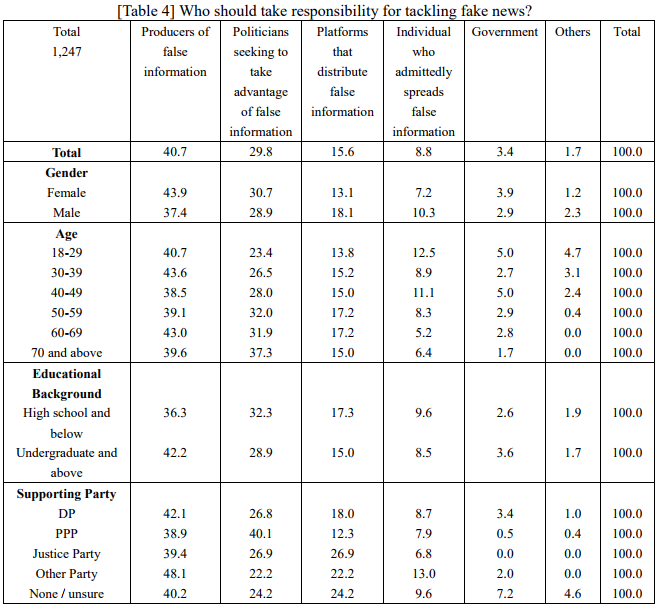

Thirdly, regarding the accountability for tackling fake news, majority of respondents, at 40.7%, believe that the creator of the fake news bears the primary responsibility. This is followed by politicians who exploit fake news for political gain (29.8%), platforms that disseminate false information without proper filtering (15.6%), and individuals who knowingly spread such information (8.8%). Only a minority, 3.4%, think the governrnent should be primarily responsible. A greater proportion of women compared to men, and individuals with a university degree or higher as opposed to those with a high school diploma or less, held the view that either the producers of fake news or politicians utilizing it for political purposes should take action. Justice Party supporters more frequently held platform companies accountable for addressing fake news (26.9%), with DP supporters showing 6% more agreement on this point compared to PPP supporters. In terms of age, there was a 14% discrepancy between the youngest (18-29) and oldest (over 70) age groups in attributing responsibility to politicians, with 23.4% and 37.3% respectively.

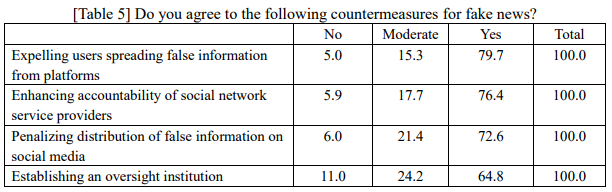

Lastly, in the context of combating fake news and disinformation, the most supported measure was the expulsion of actors who are distributing fake news from social media platforms, which received 79.7% approval. This was followed by calls to enhance the corporate responsibility of social media platforms (76.4%), and to penalize individuals who disseminate false information (72.6%). Conversely, only 64.8% of respondents favored the creation of an oversight institution tasked with monitoring fake news, reflecting a broader sentiment that individuals and platform companies should bear greater responsibility than the governrnent in addressing this issue.

While support for these countermeasures did not significantly vary across political party lines, notable differences emerged among age groups. In the case of expelling users spreading false information from platforms, the youngest cohort (18-29) showed the least support at 66.6%, with approval rates increasing with age, reaching up to 90.2% among those over 70. The trend of increasing support with age was consistent across measures: enhancing the accountability of social media companies began at 59.2% among the 18-29 age group and rose to 89.5% among those over 70; support for punishing the distribution of false information started at 60.4% in the 18-29 age bracket, climbing to 84.5% among those over 70. Agreement on establishing an oversight institution started at 52.5% among the youngest adults, dipped slightly in the 40s age group, and then increased to 81.6% among those over 70. Partisan differences were apparent in attitudes towards the establishment of an oversight body, with 61.4% of Democratic Party supporters and 75.2% of People Power Party supporters in favor, respectively.

5. Policy Recommendations for Addressing Disinformation

The rampant spread of disinformation on social media has significantly undermined their credibility. However, it is crucial not to equate widespread distrust with a call for stringent regulation. Social media serves as a vital arena for challenging authoritarianism and sharing diverse information and opinions. A Pew Research Center survey across 19 advanced economies highlighted this complexity, revealing that 57% of respondents believe social media benefits their democracy—a sentiment more pronounced in the United States, the Netherlands, France, and Australia. Particularly in Korea, 66% view social media as beneficial for democracy, a figure nearly double those who perceive it negatively (Wike et al. 2022).

Addressing disinformation requires proactive measures that do not compromise freedom of speech, the openness, and diversity of democracy. Definitions of disinformation should align with existing legal frameworks, and any move to enhance civil penalties must be preceded by educational efforts. In Korea, there is a potential to leverage entities like the Korea Communications Commission to monitor disinformation more effectively. Above all, enhancing media literacy is paramount to equip internet users with the skills to identify false information. For platform companies disseminating disinformation, there is a need for technological solutions to filter content, alongside greater algorithmic transparency and accountability. Drawing on the case of DSA, responsibilities should be clearly outlined, with non-compliance resulting in penalties. Legislative responses to disinformation should be bipartisan and consider the polarized political landscape in South Korea, seeking consensus for effectiveness. This approach mirrors European efforts to balance free speech with regulation.

Meanwhile, flow of disinformation from abroad presents a significant challenge for South Korea, necessitating responses that safeguard national and social security, especially during elections. Learning from U.S. strategies, South Korea could benefit from a unified oversight structure combining information collection and surveillance to effectively counter foreign influence.

Ultimately, the restoration of trust in traditional media as unbiased and ethical news sources stands as the most potent antidote to disinformation. Such credibility can shift reliance away from social media for political and social news, reinforcing the foundations of informed democratic engagement.

References

Broadband Commission. 2020. “Balancing Act: Countering Digital Disinformation While Respecting Freedom of Expression.” Working Group Report. September 22.

Choi, Seung Pil. 2020. “Review of Regulatory Laws on Fake News – With Focus on Mass Media Laws and Information and Communications Networks Act.” Public Law Journal

European Commission. “Tackling online disinformation.” https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/online-disinformation

___________. “The Digital Services Act package.” https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/digital-services-act-package

___________. “The Digital Services Act.” https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-age/digital-services-act_en

___________. “Supervision of the designated very large online platforms and search engines under DSA.” https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/list-designated-vlops-and-slops

___________. “DSA: Very large online platforms and search engines.” https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/dsa-vlops

Funk, Allie, Adrian Shahbaz, and Kian Vesteinsson. 2023. “Freedom On the Net 2023: The Repressive Power of Artificial Intelligence.” Freedom House.

Green, Yasmin et al. 2023. “Evidence-Based Misinformation Interventions: Challenges and Opportunities for Measurement and Collaboration.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. January 9.

Hsu, Tiffany et al. 2024. “Elections and Disinformation Are Colliding Like Never Before in 2024.” New York Times. January 9.

Humprecht, Edda et al. 2023. “The sharing of disinformation in cross-national comparison: analyzing patterns of resilience.” Information, Communication & Society 26, 7: 1342–1362.

Jeong, Sehun. 2017. “Defining Fake News and Response Strategies Home and Abraod [Translated].” Presented in Press Arbitration Committee Policy Debate. December 7.

Kang, Han-deul. 2023. “KCSC shutting down ‘fake news reporting center’ today…‘expedited review systern’ to continue [Translated].” Kyunghyang Shinmun. December 21. https://www.khan.co.kr/national/media/article/202312211722001

Kim, Yeora. 2020. “Current Status and Issues Relating to Disinformation in the 20th National Assembly [Translated].” National Assembly Resesarch Service Analysis. June 4.

Klippenstein, Ken. 2023. “The Governrnent Created a New Disinformation Office to Oversee All the Other Ones.” The Intercept. May 5.

Korea Press Foundation. 2021. “Social Media Users in Korea 2021.” December 31. https://www.kpf.or.kr/synap/skin/doc.html?fn=1641358692900.pdf&rs=/synap/result/research/

Morosoli, Sophie et al. 2022. “Identifying the Drivers Behind the Dissemination of Online Misinformation: A Study on Political Attitudes and Individual Characteristics in the Context of Engaging With Misinformation on Social Media.” American Behavioral Scientist 0,0. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027642221118300

Myers, Steven Lee. 2023. “U.S. Tries New Tack on Russian Disinformation: Pre-Empting It.” New York Times. Oct 26.

Peterson, Erik and Shanto Iyengar. 2021. “Partisan Gaps in Political Information and Information-Seeking Behavior: Motivated Reasoning or Cheerleading?” American Journal of Political Science 65,1: 133–147.

Törnberg, Petter. 2018. “Echo chambers and viral misinformation: Modeling fake news as complex contagion.” PLoS ONE 13, 9. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203958/

U.S. Department of State. 2023. “Exporting Pro-Kremlin Disinformation: The Case of Nova Resistencia in Brazil.” Global Engagement Center Special Report. October 19.

_____________. 2023. “Disarming Disinformation: Our Shared Responsibility.” Global Engagement Center. October 20.

UNESCO. 2018. “Journalism, ‘Fake News’ and Disinformation: A Handbook for Journalism Education and Training.”

________. 2023. “Survey on the impact of online disinformation and hate speech.” September.

Wanless, Alica and Jacob Shapiro. 2022. “A CERN Model for Studying the Information Environment.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. November 17.

Wike, Richard et al. 2022. “Social Media Seen as Mostly Good for Democracy Across Many Nations, But U.S. is a Major Outlier.” Pew Research Center. December 6.

[1] The issue of overlapping functions between DOS and GEC was reportedly raised during the launch of the FMIC. FMIC’s motto is “exposing deception in defense of liberty.”

[2] It is reported that Nova Resistencia is a Neo-Nazi group active in South America, Europe, and North America, deeply engaged within the Russian disinformation and propaganda ecosystern.

■ Sook Jong LEE is a Senior Fellow of EAI and a Distinguished Professor at Sungkyunkwan University.

■ For inquiries: Jisoo Park, Research Associate

02 2277 1683 (ext. 208) | jspark@eai.or.kr