1. Introduction

Following the coup d’état initiated on February 1, 2021, a total of 1,384 people had died and 11,289 had been arrested as of December 31. Between February 1 and December 10, the military launched 7,053 attacks against civilians and citizen forces, an increase of 664% compared to 2020 (ALTSEAN 2022/01/05, 1, 4). Of 593,000 internally displaced people (IDP), 223,000 have become displaced following the coup (OCHA 2021, 17).

Although the coup was a military decision, the cause can be explained by civilian military relations. That is, the civilian government led by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi neglected the military, and there were periodic emotional confrontations between the leaders of each faction. The military, acted out of a desire to regain its own status and function as a patriotic group defending the federal Union, even if it relied on force. However, the division of the society and the conflict between the people were not explicit like the military claimed, so their use of the political intervention justification to seize control of the government seems absurd.[1]

If the military's previous three political interventions of 1958, 1962 and 1988 occurred across a continual political decline and state of low national development, then the military coup of 2021 is a reactionary attempt to return the country to the past in a completely new political and social direction. If a formal representative system is set up through a general election in August 2023, Myanmar will return to a military-oriented society, and there will be heavier social and political costs involved in the country's reconstruction compared to now.

The military's regressive behavior in the process of Myanmar's normalization does not only mean political decline. It will expose the structural problems and bring about a crisis in all sectors of society. Myanmar has already become a failed state under the half-century of military rule, but the military wants to rebuild its traditional dynasty that gives it reign over the people. The country has reached an inflection point where the crises of the past will be repeated.

2. Adding Insult to Economic Injury: The Effects of a Coup Perpetrated by a Military Overwhelmed by the COVID-19 Pandemic

From 1988 until March 2011, the military government announced that average annual economic growth was double digit, but nobody believed this. In the junta, the personnel in the Central Statistical Organization distorted the numbers out of fear of offending their superiors and losing their jobs. This behavior was a very important characteristic of bureaucratic society. The Thein Sein's administration (2011-2016) promoted the establishment of an accurate statistical system in accordance with its drive to erase the chronic maladies of the country's bureaucratic society and push for reform and opening up.

This tendency of the military to distort reality appears to be experiencing a revival. For example, on December 7, 2021, Minister Aung Naing Oo of the Ministry of Investment and Foreign Economic Relations claimed that Myanmar's GDP growth rate of -18% was unreliable data from those opposed to the regime. He claimed that the real GDP growth was -8 to 9%, and that post-pandemic growth would exceed the IMF's forecast of 2.5% (Duangdee 2021/07/26; Nitta 2021/12/10; World Bank 2021/07/23). Other major institutions forecast Myanmar's economic growth for 2022 at -4 to 5%, also deviating from the Minister's predictions.

Contrary to the claims made by Minister Aung Naing Oo, Myanmar's economic recession following the coup has been serious, increasing the possibility that the people's standard of living will regress to the level that it was under the previous military government. According to the UNDP, the biggest factor impacting household income since February 1, 2021 has been the coup (75%), followed by the pandemic (25%) (UNDP 2021, 35).

Between the end of 2019 and July 2021, 3.2 million people lost their jobs due to the pandemic, with millions more being forced to reduce their working hours (ICG 2021, 8). Since shortly after the coup, the value of the kyat (MMK) has declined against the US dollar, falling 33% between January and November 2021 (OCHA 2021, 14). The international community has sounded the alarm over the crisis in Myanmar. UNDP warned that by the beginning of 2022, nearly half of Myanmar's population of 55 million, or 25 million people, are expected to be living below the national poverty line, a return to pre-2005 living standards (UNDP 2021/12/01).

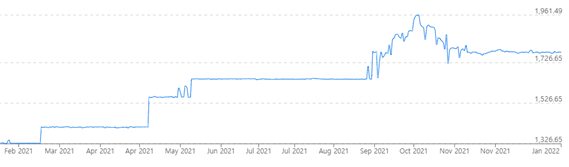

These warning signs are expected to be exacerbated by the falling exchange rate. The Central Bank of Myanmar sold a total of $88 million USD on six occasions in December 2021 alone to mitigate exchange rate fluctuations (GNLM 2021/12/25). At the time of this writing, the exchange rate has not skyrocketed (see figure). However, in December 2021, the government imported 35 tons of paper for banknotes from Uzbekistan to cover military expenditures and reduced tax revenue. If the amount of money in circulation increases, it will guarantee inflation. The previous military government also frequently increased the amount of currency it issued and circulated without considering market conditions.[2]

(Source: https://www.xe.com/currencycharts/?from=USD&to=MMK)

Due to the coup, the number of applications for business registration decreased by 44% in 2021 (Walker 2021/12/01). However, in an effort to break through the increasingly strong Western sanctions, the military is mobilizing the companies that it runs and promoting economic cooperation with China in order to pursue its interests. For example, when the border reopened in November 2021, Chinese companies began to restore exchanges in the extraction industries monopolized by the military such as rare earths, precious stones including rubies and jade, crude oil, and natural gas. The Western world, including the United States and European Union, has imposed targeted sanctions against high-ranking military personnel and military-owned companies, while NGOs at home and abroad demand the severance of relations with Myanmar's military, including divestment from military-owned companies. The Western society previously imposed comprehensive sanctions against Myanmar for over 20 years, but it proved ineffective.

In order for sanctions against Myanmar to succeed, the economic influence of large countries like China must be minimized, and sanctions simultaneously implemented by participating countries. The Biden administration has been the target of lobbying and objections from Singaporean and Thai oil refiners, including Chevron, and the senior members of Myanmar's military keep their funds in Southeast Asian countries, not the US or EU. It seems as though it will be impossible to choke off the funds of the military considering the circumstances. In fact, the military recognizes that cooperation with Chinese capital is not advantageous over the medium to long term, but there are no realistic alternatives. The cozy relationship between China and the military will further strengthen anti-Chinese sentiment among both the military and the general public.

The military's response to COVID-19 has also been within the realm of expected behavior, as crisis management is not a strong point. The military claims it implemented full measures against COVID-19 after the large-scale resistance fizzled out in August 2021. As of December 28, 2021, the Ministry of Health announced that 13.45 million adults had been fully vaccinated, and that they had achieved their target of fully vaccinating 50% of the population by the end of 2021 (GNLM 2021/12/28). However, there is no objective statistical data indicating that more than 10 million people were vaccinated over a period of about three months, and the military claims that the majority of its vaccines are from China, where people are reluctant to be inoculated. Verification of the claim that the omicron variant has not been found in the country is also needed. While the military has claimed it will produce its own vaccine in 2022 with China's support, the specific plans, such as the preparation of production facilities and the introduction of the necessary human resources, are not clear.

In July 2021, individual houses where all of the family members inside were infected with COVID-19 began putting out yellow flags to ask for help. However, the military cut off supplies of oxygen, making the preposterous assertion that if people memorized Buddhist scriptures they would recover. At the time, the military was more concerned with taking control of the country than with the lives of the people, and had already designated those who participated in anti-regime protests as terrorists. People retorted with the question of whether the military would embrace those who didn't participate in the protests.

3. Interregional and Intergenerational Cracks: Social Conflict and the Possibility of Integration

The military's confidence in its ability to take control of the government through a coup is based on the conviction that they have their own weapons, and the people can never form a national coalition to rise up in response. The military continues to cling to its claim that Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs) tried to divide the Union in 1962, and thus the military must remain in power to prevent this from happening. The Burmans as majority have shown no concern or compassion, let alone support, for Myanmar's minority populations, and as a result ethnic minorities have suffered repression and become strangers in their own land. Therefore, ethnic minorities are not interested in whether those who took control of the regime are military or civilians, and see the military coup as a hegemonial conflict between the Burmese political elites (Ardeth Maung Thawnghmung and Noah 2021, 301). This perspective did not change during the 8888 Uprising and the Saffron Revolution of 2007. Myanmar could have headed in a different direction if ethnic minorities had joined forces with the protesters during these two political upheavals.

Both governments since 2011 have adopted national reconciliation and national integration through a ceasefire agreement with the EAOs as a top priority. As a result, at the end of the Thein Sein's government, eight of the 15 EAOs signed a Union-level ceasefire agreement. Daw Aung San Suu Kyi's government changed direction yet again and implemented four ceasefire agreements under the name of the twenty-first century Panglong Conference.

While there is no evidence that minorities supported Daw Aung San Suu Kyi's government, they at least anticipated that it would take a different line than the military, which favored violence and forced annexation. The government, military, and EAOs were all the subject of negotiations, but the government consistently failed to take care of the EAOs, and the military played the two sides against each other. The ceasefire agreement accordingly failed to materialize. In addition, the National League for Democracy (NLD) suffered defeats in minority areas in the 2017 and 2018 by-elections, which gave rise to suspicions about the national unity of the government and the ruling party.

Given this background, the National Unity Government's (NUG) aspiration to form a federal army in solidarity with the EAOs is unrealistic. Some of the EAOs have been supporting the People's Defense Force (PDF) by providing military training and weapons, but it is highly unlikely that the EAOs will suddenly join the PDF. If the NLD had approached minority populations with sincerity, the groups might have been able to build mutual trust.

In early 2022, the military announced a unilateral ceasefire until the end of the year without any agreement of each EAOs. However, the military has continued its indiscriminate offensive military campaign in the areas where the PDF is believed to be active. The roughly 8,000 PDF soldiers are inadequate to fight against the more than 400,000 regular soldiers so called Tatmadaw (armed forces). Following the defeat of the democratization movement of 1988, a group of youths organized the All Burma Students' Democratic Front (ABSDF) to overthrow the military through armed struggle and went into the jungle. Their armed struggle did not last more than five years. Skirmishes between the regular army and the PDF will only increase the harm suffered by locals.

On February 17, 2021, a leader of the 88 Generation Min Ko Naing called for national unity, stating "This revolution against the military dictatorship is a combined resistance of generations X, Y, and Z" (Jordt et. al 2021, 18). However, in actuality everyone who filled the streets or was arrested as a protest leader was a member of Gen Z only. While some members from the 88 generation attended the demonstrations, leaders abstained from making political remarks or actions. Instead, the youths performed a kadaw, or big bow, in the temple even as their parents tried to dissuade them and then went out into the streets. Why did only young people fill the streets?

Myanmar's Generation Z is a kind of product of the country's political reform and opening up. For the last 10 years, Myanmar's economy has grown annually by 6-8%, with the success of the economy being up to the people. The spread of mobile phones allowed the public to express and share their political opinions online. Since its opening, opportunities for direct contact with foreigners and the ability to experience international standards and foreign ways of thinking firsthand have increased, especially for Gen Z, which has firmly established the principle of justice.

In contrast, the older generation has memories of being defeated by the military and is accustomed to a life that values a secure livelihood above resistance. This was repeated in 2021, as the price of basic necessities such as cooking oil and refined oil soared following the coup. About 76% of households maintained their lifestyles by reducing non-food consumption (ICG 2021, 8; UNDP 2021, 31). In other words, monks and members of the older generation who have experienced or witnessed the cruelties of the military firsthand have not taken easily to the streets, while twenty-something youths are convinced they can change the world. However, the absence of leadership to gather and express the will of the movement was a blind spot in the democratic movements of the past.

In April 2021, the deposed democratic faction established the National Unity Government (NUG) with the support of the people to end military rule and restore democracy, but its performance has been unsatisfactory. First of all, it is questionable whether or not NUG's status has placed it within close contact of those who oppose military rule. Although the NUG expressed its condolences every time an NLD member died of COVID-19, it did not respond to any of the street casualties. In September 2021, the NUG made a propaganda announcement against the military, inciting the people to become heroes or patriots by sacrificing themselves. It cannot be said that the organization's activities are progressive. The NUG doesn't appear to be an organization that seeks to separate itself from the people and reign from on high.

The second issue is the NUG's activities. The NUG cabinet consists mainly of NLD party members and ethnic Burman with no actual executive or legislative experience, who confine their activities to the internet due to a fear of being arrested by the military. Because they lack expertise and a transparent decision-making process, the NUG thus far has only demanded that the international community, not the military, recognize them as Myanmar's official government. This behavior is no different from that of the government-in-exile the National Coalition Government of the Union of Burma (NCGUB), whose singular achievement from its creation in 1990 until its dissolution in 2012 was the promotion of the use of the name Burma not Myanmar. The NUG does not have the right to be a symbol of democratization in Myanmar or to monopolize leadership over the democratic faction, and it does not have the full support of the people. Instead of slogans and incitement, the NUG must work together with the people to propose, push for and implement realistic countermeasures than can win against the military.

4. Conclusion: Finding Hope in Crisis

Since the coup, Myanmar has been in a social and economic crisis that it seems unable to escape unless the military’s back to barracks or resigns. Nevertheless, this coup has had unexpected consequences that will awaken the people. These include internal criticism within the democratic faction as well as an objective understanding of the history of Myanmar's oppressed minorities. Daw Aung San Suu Kyi was a symbol of democratization in Myanmar, but her actual performance as a politician was not great. Her status as a kind of saint meant that criticism of her actions was not tolerated, and the NLD government became the government of and for Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. Generation Z has criticized this concentration of power on certain figures, and has resisted the military so strongly not to restore Daw Aung San Suu Kyi to power, but to restore democracy.

Some politicians have apologized for the behavior of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi's government, which ignored human rights in ethnic minority areas, including the Rohingya, as a political calculation. However, the young generation will no longer be duped by the military's strategy to distort history surrounding minorities and maintain the regime's power on the pretext of potential conflict between the Burman and ethnic minority groups. Myanmar youths living in Korea have begun to debate whether they should shed their ethnic identities and exist simply as members of a federal Union. This coup has served as a turning point for the foundation for national reconciliation and integration in the future in order to confirm solidarity and sense of community among groups in the Union.

Despite ongoing crises in numerous sectors, the military continues to adhere to its tactics of the past, but the people seem to be preparing for the future. If the military wants to survive for a long time in the political arena, they won't be helped by the displays of force perpetrated by their predecessors. The military will have to reflect on why President Thein Sein, who was a soldier, received so much support from the people. ■

References

ALTSEAN. Coup Watch Special Edition: A Year of Struggle in Burma. Bangkok: ALTSEAN. 2022/02/09.

Ardeth Maung Thawnghmung and Khun Noah. 2021. “Myanmar's Military Coup and the Elevation of the Minority Agenda?” Critical Asian Studies. 53(2). 297-309.

Duangdee, Vijitra. “World Bank: Coup and Coronavirus Shrink Myanmar’s Economy by 18%.” VOA(Voice of America). 2021/07/26.

GNLM(Global New Light of Myanmar). 2021/12/25; 2021/12/28.

ICG(International Crisis Group). 2021. The Deadly Stalemate in Post-coup Myanmar. Asia Briefing No.170. Yangon/Bangkok/Brussels: ICG.

Jordt, Ingrid, Tharaphi Than and Sue Ye Lin. 2021. How Generation Z Galvanized a Revolutionary Movement against Myanmar’s 2021 Military Coup. Trends in Southeast Asia Issue 7. Singapore: ISEAS.

Nitta, Yuichi. “Myanmar to End Kirin Row Based on Law: Investment Minister.” Nikkei Asia. 2021/12/10.

OCHA. 2021. Humanitarian Needs Overview: Myanmar. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/mmr_humanitarian_needs_overview_2022.pdf

Steinberg, David I. 2021. The Military in Burma/Myanmar: On the Longevity of Tatmadaw Rule and Influence. Trends in Southeast Asia, Issue6. Singapore: ISEAS.

UNDP. 2021. People’s Pulse: Socio-economic Impact of the Events since 1st February 2021 on Households in Myanmar. Yangon: UNDP Myanmar Office.

_____. “Myanmar Urban Poverty Rates Set to Triple, New United Nations Survey Finds” 2021/12/01.

Walker, Tommy. “Myanmar’s Coup Economy is ‘Boom and Bust’.” VOA. 2021/12/01.

World Bank. “Myanmar Economy Expected to Contract by 18 Percent in FY2021: Report.” 2021/07/23.

[1] To know more about the background of the coup, please refer to the text of Steinberg (2021, 30).

[2] The current military government's policy to restrict access to information is also being followed by the past practices. Before smartphones were commercialized from the late 1990s to the early 2000s, military authorities proposed an online access to information while maintaining a price of a SIM card around $2,000 to $3,000. In December 2021, in order to weaken the rebels' contact system, including that of the People's Defense Force (PDF), the military doubled the price of mobile data and imposed 20,000 Kyat (which was a price of 1.15% rise) for the SIM cards that initiated the services in January 2022.

■ Jun Young Jang is a Research Professor at the Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, Seoul, Korea. Dr. Jang received his Ph.D. in International Relations from HUFS and his M.A. degrees in Southeast Asian Studies from Sogang University. He was a senior research fellow at the Center for Southeast Asian Studies, a research professor at the Center of North Bay of Bengal, Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, where he conducted research on Southeast Asian Politics and Myanmar Studies. He published books relating to Myanmar such as Change of Myanmar’s Foreign Policy and Foreign Relations with Major Countries, Political Economy & Reform and Open of Myanmar: Assessment and Challenge, Harp and Peacock: 70 Years of Modern Myanmar Political History, Basic Myanmar Language. He contribute to various Myanmar issues in a number of media outlets.

■ Typeset by Juhyun Jun Head of the Future, Innovation, and Governance TeamㆍResearch Associate

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 204) | jhjun@eai.or.kr