Editor's Notes

Following the democratization in 1987, South Koreans seem to enjoy the free press and various forms of media outlets. In this issue briefing, Prof. Kyu Sup Hahn examines the public preference for news outlets as well as the public trust in the media, based on the findings from the 2020 Korean Identity Survey. Prof. Hahn argues that South Koreans were sharply divided in their preference for news sources along the line of their political orientation, suggesting the polarization of the media outlets. Prof. Hahn further argues that South Koreans’ preference for news sources are not necessarily aligned with their preference for policy issues, suggesting that people do not necessarily trust media outlets representing their policy preference. Prof. Hahn concluded that preference for news sources has become a social identity in South Korea, reinforcing the existing political polarization in the country.

Paradox of Press Freedom in South Korea

The 1987 democratization finally granted South Koreans press freedom. More than thirty years have passed thereafter, allowing the Korean news media for plenty of time to mature. South Korea has become a country best known for its high-speed Internet and smartphones. Besides, the rapid growth of one-person media has been regarded as an expansion of free speech. Unarguably, there seems no shortage of the free press in South Korea.

As news portals account for a large portion of news circulation in South Korea, the number of news organizations has skyrocketed. If a news source is included in portals’ search result pages, it can lure a fair volume of traffic online. As a result, more than six thousand registered news outlets are currently in operation in the country with a population of just over 50 million. With respect to press freedom, South Korea seems to have become a country that everyone had envisioned prior to the 1987 democratization.

Despite the increased press freedom, the South Korean public have become highly discontent with news media in the country. According to the Digital News Report 2020 published by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism[1], South Korea ranked in the last place in terms of media trust for the five consecutive years since 2016. Only 21% of South Koreans “trusted news media they used”, whereas the global average was approximately 46%.

In a similar vein, according to the 2016 Kantar Public poll, more South Koreans expressed their trust in Samsung than they did in all the major news outlets. Quite surprisingly, even the self-identified conservatives and liberals expressed slightly a higher level of trust in Samsung than they did in conservative and liberal newspapers. Clearly, few South Koreans acknowledge news media as a watchdog of society. After enjoying thirsty years of freedom, the status of South Korean news media as the fourth estate has become more of a self-congratulatory gesture.

2020 Korean Identity Survey

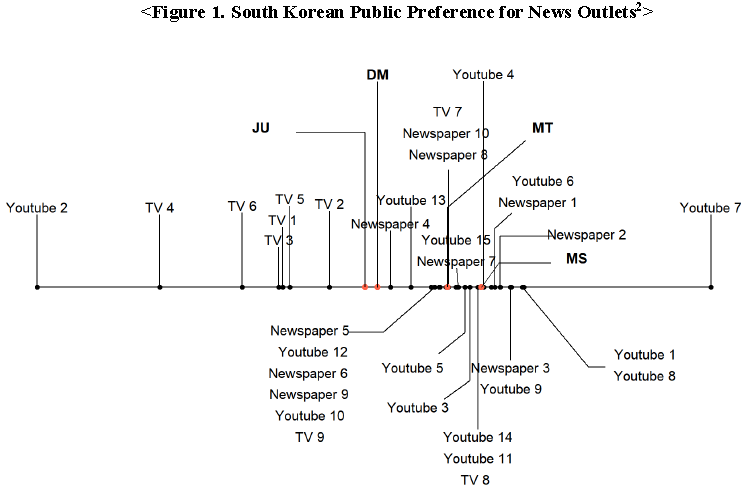

In May 2020, the East Asia Institute (EAI) administered its fourth Korean Identity Survey. Representative samples of 1,000 Koreans were interviewed face-to-face. This year’s survey asked respondents how much they trusted individual news outlets in the country. As shown in the Figure 1, the list encompassed the total of 34 news outlets, including three major broadcasting networks (KBS, MBC, and SBS), four so-called TV channels of comprehensive programming (TV Chosun, JTBC, Channel A, MBN), two news channels (YTN, Yonhap News TV), and ten newspapers with the highest circulation rates. Additionally, the EAI survey included fifteen Youtube channels specializing in current political affairs that are popular among the public.

Respondents’ trust in news outlets was measured on a five-point scale, based on so-called Polytomous Item Response Model. This type of model is often used to estimate an examinee’s scholastic aptitude in standardized tests such as SAT or TOFLE. In an academic testing, it allows for estimating the difficulty of each question and juxtaposing it with the ability of examinees on the same scale. Based on this model, respondents and news outlets were placed on the same scale. News organizations received a score based on how likely the same respondents rate them as “trustworthy.”

Divided News Source Preference

According to the 2020 Korean Identity Survey conducted above, South Koreans were sharply divided in their news source preference. Of 34 news outlets, only nine fell in between the average supporters of the ruling Democratic Party (DP) and the opposition Unified Future Party (UFP)[3]. This shows that liberals and conservatives alike do not trust the news outlets belonging to the opposite political camp.

Surprisingly, all three broadcast networks, of which two are publicly funded, fell in the far left end of the ideological spectrum. Two publicly funded broadcast networks appealed mostly to avid supporters of the incumbent government. Such skew in the audience base of public broadcasters can be controversial; for example, BBC’s audience base would consist of a more balanced mix of voters. Likewise, preference for the two publicly funded news channels also fell in close proximity to the three broadcast networks. When compared with the three broadcast networks, even the two most liberal newspaper (Newspapers 4 and 5) attracted relatively moderate news consumers. In short, the cluster of like-minded news consumers seems unmistakably clear.

In sharp contrast, twelve out of fifteen Youtube channels were located right for the preference of average UFP supporters. Many Youtube channels seemed to appeal to conservative news consumers. Unlike in Europe or the U.S., government’s influence on publicly funded broadcast networks seems quite pervasive in South Korea. After a transition from one government to another, top executives at major broadcast networks such as KBS and MBC are forced to resign. Likewise, nearly everyone holding important editorial positions in news production is forced out and replaced with those on the ‘winning’ side.

Disapproving the publicly-funded broadcast networks, critics of the incumbent government seem to have turned to social media. Likewise, when Twitter first penetrated into the South Korean society in the early 2010s under the Lee Myung-bak government, a disproportionately large number of liberals used it to access political news. Now, with President Moon Jae-in in office, many conservatives seem to have turned to Youtube channels for political news. In short, news from broadcast networks is largely consumed by supporters of the incumbent government, whereas a large proportion of Youtube news consumers consist of supporters of the opposition party.

Finally, it is interesting to see that Youtube channels are located at both extremes of the ideological spectrum. Although a vast majority of Youtube channels appealed to conservative news consumers, the most liberal news consumers also turned to Youtube 2. Likewise, Youtube 7 is located at the conservative extreme. This indicates that ideological extremism can be a highly effective niche marketing strategy to attract news consumers.

News Source Preference as an Affective Choice

What accounts for this sharply divided news source preference? Generation, party identity, and gender turned out to be statistically significant predictors of news outlet preference. News consumers in their 30s strongly preferred the liberal news outlets. As expected, DP supporters were more likely to prefer the liberal news outlets when compared with others. Also, male respondents preferred the liberal news outlets.

Does news consumers’ policy preference reflect their news source preference? EAI asked respondents about their preference regarding twelve policy issues based on the Polytomous Item Response Model, and attained individual news consumers’ policy preference scores. The analysis showed that policy preference had little to do with news consumers’ preference for new sources. They did not necessarily trust news channels representing their policy preference.

It is well-known that South Korean news consumers are strongly inclined to avoid news professing disagreeable views. According to the Digital News Report 2020, 44% of South Korean news consumers said that they preferred the news outlets sharing their political views. Among 40 countries included in the study, the average was approximately 28%. Only Turkey (55%), Mexico (48%), and the Philippines (46%) came ahead of South Korea. On the other hand, over 70% of British, German and Japanese news consumers preferred “neutral” news outlets, whereas only 4% of Koreans did.

In conclusion, preference for news sources has become a social identity in South Korea, reinforcing the existing political polarization among the South Korean public. Thirty years after the democratization, South Koreans seem to be caught in a vicious cycle of polarization with the news media facilitating it.■

[1] Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism https://www.digitalnewsreport.org/survey/2020/overview-key-findings-2020/

[2] Editor’s Note: JU refers to Justice Party; DM refers to Democratic Party of Korea (ruling party); MT refers to People Power Party(main opposition), and MS refers to the Livelihood of the People Party. Due to the sensitivity around political orientations of each news outlets, names of each news outlets have not been disclosed in the figure above.

[3] Editor’s note: The conservative party changed its name to “People Power Party” as of September 2 2020 https://ko.wikipedia.org/wiki/%EA%B5%AD%EB%AF%BC%EC%9D%98%ED%9E%98

■ Hahn, Kyu Sup is currently a Professor at the Department of Communication at Seoul National University. He received his Ph.D. in communication at Stanford University, and previously taught at UCLA. His areas of research are mainly political communication. His publications include “Economic and Cultural Drivers of Support for Immigrants.” (2019), “The Influence of “Social Viewing” on Televised Debate Viewers’ Political Judgment”, amongst others.

■ Typeset by Eunji Lee, Research Associate/Project Manager

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 207) | ejlee@eai.or.kr

The East Asia Institute takes no institutional position on policy issues and has no affiliation with the Korean government. All statements of fact and expressions of opinion contained in its publications are the sole responsibility of the author or authors.