Soo-Am Kim is Director of Research Management Division and Senior Research Fellow at Korea Institute for National Unification (KINU), Seoul, Korea. He serves as a member of the Policy Advisory Committee for the Ministry of Unification.

The international community has contributed diverse efforts as the poor situation of human rights in North Korea has been unveiled by North Korean defectors. The United Nations has demanded improvements in the human rights record of North Korea based on monitoring via the Human Rights Council (formerly known as the UN Commission on Human Rights), the UN Resolution on the Situation of Human Rights in the DPRK, and assigning a Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the DPRK.

As North Korea consistently refuses and denies attempts at monitoring human rights, the international community has had to investigate new approaches to induce a change of attitude. In particular, they have focused on the common practice of ‘impunity’ for human rights violators in North Korea as one of the main reasons why human rights violation continues in North Korea. As a result, in March 2013, UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) adopted the UN resolution on the Situation of Human Rights in the DPRK. This resolution launched the Commission of Inquiry on human rights in North Korea which mandates ‘full accountability.’

The Commission of Inquiry launched a one-year temporary investigation project. The Commission officially submitted the report to UNHRC in February 2014. On the basis of this report, the UN’s North Korean human rights improvement activity shifted from ‘monitoring-oriented’ to ‘accountability-oriented.’ This issue briefing is going to trace the changes of North Korean human rights improvement through the UN Human Rights mechanism. By reflecting on these changes, it attempts to suggest a strategic direction for DPRK’s human rights improvement.

UN Human Rights Mechanisms and the Change in North Korea’s Human Rights Issues

Expansion of Engagement in North Korean Human Rights Issues by UN Human Rights Mechanisms

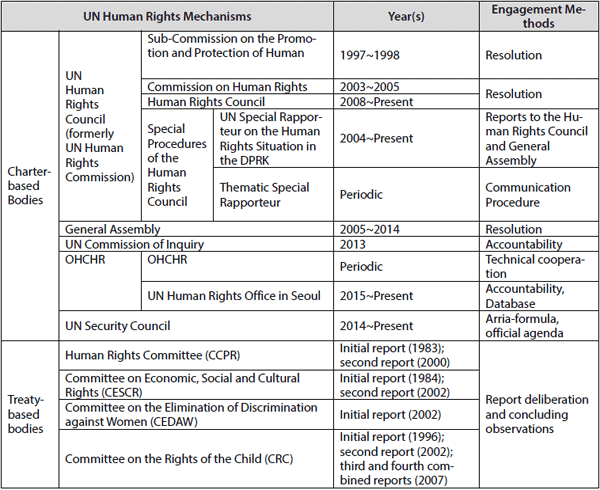

There have been significant changes to the UN human rights mechanisms for engaging North Korean human rights issues since the investigation from the Commission of Inquiry. UN human rights mechanisms are largely divided into charter-based bodies and treaty-based bodies. While the former consists of state representatives and has strong political characteristics, the latter is a non-political entity composed of experts.

The UN human rights mechanisms are expanding their level of engagement in North Korean human rights issues through the Commission of Inquiry. The following are changes in how UN human rights mechanisms are involved in North Korean human rights issues.

First, the Human Rights Council, one of the representative UN bodies engaged in work on human rights, is involved in North Korean human rights issues. There are four specific mechanisms: General Assembly, Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights, special procedures, and Universal Periodic Review (UPR). The General Assembly and Sub-Commission are using the resolution method to deal with North Koran human rights issues. The special procedure of UNHRC is concerned with human rights violations in DPRK. First, based on the UN Resolution on the Situation of Human Rights in the DPRK by the Commission on Human Rights, a Special Rapporteur on North Korea’s human rights situation was appointed and has been active since 2004 as part of the country-specific special procedure.

The Special Rapporteur monitors the situation of human rights in the DPRK and then submits the report to UNHRC and General Assembly annually. The thematic special procedures are also involved in the North Korean human rights issue according to their mandate.

UPR, a newly founded human rights mechanism from the UN Human Rights Council founded in 2006 to replace the former institution of UN Human Rights Commission, is also concerned with North Korean human rights. North Korea submitted its first state report in 2009 and its second report in 2014. It also dispatched delegations to engage in mutual dialogue with member states.

Second, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) is trying to promote technical cooperation in the area of human rights with North Korea. In return for offering technical support through the DPRK permanent representative to UN Office at Geneva, OHCHR is requesting Pyongyang’s cooperation.

Third, the UN General Assembly is also concerned about North Korean human rights. According to the UN Resolution on the Situation of Human Rights in the DPRK passed by the UN Human Rights Commission in 2005, the UN General Assembly is to handle North Korean human rights issues if North Korea does not adopt a positive and future-oriented attitude. Following this suggestion, the Resolution on the Situation of Human Rights in the DPRK has been passed consistently beginning in 2005 to 2014.

Fourth, implementation of the Commission of Inquiry was critical in changing UN Human Rights mechanisms. UN human rights mechanisms are expanding beyond the results of temporary activity-based involvement from the Commission of Inquiry. In a report submitted to the UN Human Rights Council, the Commission of Inquiry urged the UN Security Council to refer the situation of human rights in the DPRK to the International Criminal Court (ICC). However, China and Russia, permanent members of the UN Security Council, oppose the referral to the ICC, thereby prohibiting this from being accomplished. Meanwhile, the UN Security Council is participating in the North Korean human rights issue through different methods: the UN Security Council used an Arria-formula meeting to unofficially discuss human rights in the DPRK on April 17, 2014, and then selected the North Korean human rights issue on the official agenda on December 22, 2014.

Following the Resolution on the Situation of Human Rights in the DPRK adopted by the UN Human Rights Council in March 2014, UN Human Rights Office in Seoul, a field-based structure of the OHCHR, was set up in Seoul on June 23, 2015. By opening the independent field office, the human rights mechanism concerned with North Korean human rights has expanded its involvement. UN Human Rights Office in Seoul has the following four missions:

First, strengthen the monitoring and documentation of the situation of human rights in the DPRK; Second, secure accountability;

Third, enhance engagement and capacity building with the Governments of All states, civil society, and other stakeholders;

Fourth, maintain the visibility of the situation of the human rights in DPRK including through sustainable communication, advocacy, and outreach activities.

Not only charter-bodies but also treaty-bodies are involved in human right issues in North Korea. North Korea is a member state of Human Rights Committee (CCPR), Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), and Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC). But these treaty-based bodies are able to get involved only when North Korea observes the treaty obligation by submitting the state report and dispatching the delegation. North Korea submitted a second report to CCPR in 2000, a second report to CESCR in 2002, an initial report to CEDAW in 2002, and third and fourth combined reports to CRC in 2007. Because North Korea has not submitted any state report since 2007, treaty-based bodies has not been able to address the human rights issue in North Korea.

Figure 1: Engagement in North Korean Human Rights Issues through UN Human Rights Mechanisms

Transformation of Engagement in the North Korean Human Rights

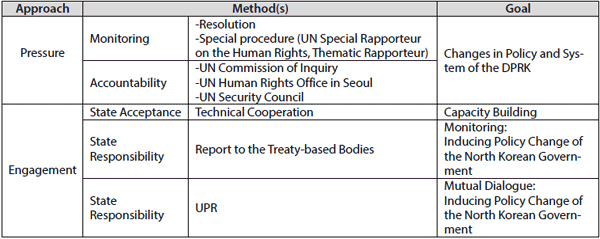

There has been a fundamental change in UN’s approach to North Korean human rights after the establishment of the Commission of Inquiry. The UN basically has applied a ‘two-track approach’ of ‘pressure’ and ‘engagement’ to enhance the North Korean human rights situation. In particular, in order to prevent, protect, and promote the human rights of the North Korean people, the UN has been attempting to induce— through the two-track policy—changes in Pyongyang’s perception and policy in relation to human rights, institutional changes, and capacity-building.

UN’s strategy of using pressure to improve the situation of North Korean human rights is accomplished through monitoring and accountability. Before the Commission of Inquiry was enacted, resolutions and monitoring through the special procedure were the basic forms of pressure. The UN’s strategy of using pressure has shifted its orientation from monitoring to accountability after the Commission of Inquiry was launched.

Together with the strategy of using pressure, UN has used a strategy of engagement by combining treaty-based bodies, UPR, and technical cooperation from OHCHR to resolve North Korean human rights issue.

Figure 2: UN’s Strategy to Improve North Korean

Changing North Korean Responses

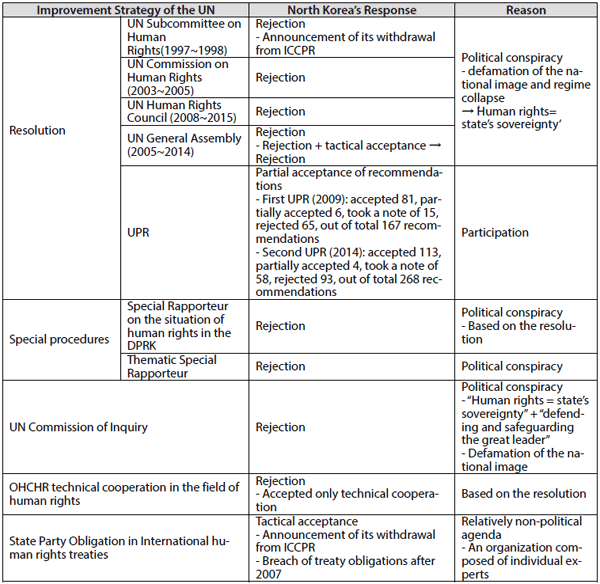

North Korea is responding to the UN’s involvement in the North Korean human rights issues by linking the human rights with the security, national image, and identity. Therefore, it is possible that the whole situation of the North Korean human rights is not fully understood if one looks only at the “human rights aspect.” The UN’s decision to change its method of putting pressure on North Korean human rights issues after the establishment of the Commission of Inquiry acts as the key factor in influencing Pyongyang’s response.

In the 2000s, North Korea responded to the UN’s request for improving its domestic human rights situation by stating that this was a violation of its national sovereignty from the perspective of North Korea’s national security. In accordance with its national security interests, Pyongyang has been adopting a ‘denial strategy’ when it comes to responding to UN pressure. Furthermore, North Korea explicitly stated that it would reject any UN’s attempts at engagement should the UN keep on pressing North Korea on the human rights issue. For instance, although North Korea welcomes the mere idea of technical cooperation with OHCHR, it will not proceed to work with OHCHR because the cooperation is predicated on the North Korean Human Rights Resolution. Because North Korea is using an approach of linking pressure and engagement, the UN’s two-track strategy of pressure and engagement has not yielded any apparent outcomes.

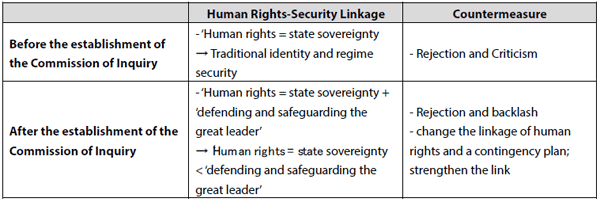

With the shift in the UN’s pressure strategy toward being accountability-oriented, North Korea’s method of linking human rights with security and with national identity is also changing. North Korea defines this accountability-based pressure strategy as targeting their highest leader, to whom they refer as ‘Supreme Dignity.’ While monitoring-based pressure such as the Resolution on the Situation of Human Rights in the DPRK targets a state, accountability-based pressure is targeted at an ‘individual.’ This perception leads North Korea to shift its human rights-security linkage toward “defending and safeguarding the great leader” while maintaining the comprehensive position that human rights fall under the state sovereignty. In other words, although a practice of defining the human rights in terms of regime security continues in North Korea, individual security for the “Supreme Dignity” has been added so that the linkage between the human rights and national security has been strengthened.

Figure 3: North Korea’s Response to the Two-track Strategy by UN

Changes in the linkage between human rights and national security is a key factor in influencing North Korea’s reaction toward the UN’s two-track strategy to improve the situation of North Korean human rights. Linking human rights with the state sovereignty was a loosely-woven linkage, which induced North Korea to respond with a denial strategy. However, with “defending and safeguarding the great leader” being established as the core objective in responding to the North Korean human rights issues, organizations and elites within the DPRK are desperately struggling for their survival in a competition for greater loyalty.

In 2014, North Korea adopted a diplomatic strategy with the perspective of “defending and safeguarding the great leader” in order to prevent the inclusion of a suggestion for the UN Security Council to refer the situation of North Korean human rights to ICC in the UN Resolution on the Situation of Human Rights in DPRK. To better advance the North Korean position, its Foreign Minister Ri Su-yong attended the UN General Assembly for the first time in 15 years, and Kang Sok-ju, Secretary of the Korean Workers’ Party, visited Europe. Also, North Korea agreed to several measures such as allowing the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the DPRK to enter North Korea, accepting OHCHR’s technical cooperation, and human rights dialogue in the process. They even expressed tactical acceptance’ to accommodate the UN’s engagement strategy previously rejected by North Korea if the suggestion to refer the issue to the ICC, which was perceived to target the “Supreme Dignity,” was dropped from the North Korea Human Rights Resolution. Even though North Korea undertook a desperate measure to defend and safeguard the great leader, the Resolution including the suggestion to refer the North Korean human rights issues to the ICC was adopted in UN General Assembly as planned. Consequently, North Korea not only returned to its strategy of denial, but it went further by applying a strong counteroffensive strategy toward international society by mobilizing various extra-governmental organizations.

Figure 4: North Korea’s Method of Linking Human Rights and Security

Based on its perception of the U.S. “hostile policy,” North Korea is responding by linking human rights with national security. North Korea also claims that the UN and other countries’ pressure on North Korea with regards to the human rights issue are due to the U.S. sponsored “hostile policy” and “policy of smothering the DPRK.” Furthermore, North Korea criticizes South Korea as being subordinate to the U.S. and argues that South Korea merely acts in a manner the U.S. would prefer. The involvement of the UN and other countries in the North Korean human rights problem is branded as the United States’ efforts at mobilizing “Instigation and Followership” and the involvement of South Korea in North Korea’s human rights is criticized by Pyongyang that South Korea is a ”Subordinate and Follower” of the U.S.

The UN’s accountability-based pressure strategy, combined with the establishment of the Office of Human Rights in Seoul, is exerting influence on inter-Korean relations. North Korea heavily criticized that the establishment of the Office of Human Rights in Seoul is regarded as “a public proclamation of confrontation” and “an excuse for instigating a war to realize the delusion of unification through absorption,” and that “there will be severe and merciless punishment” in the Committee for the Peaceful Reunification of Korea’s Secretariat Report No.1094 on May 29, 2015. North Korea went beyond mere criticism and took measures such as not participating in the Gwangju Summer Universiade on June 19, 2015 and sentencing two South Korean detainees to an indefinite period of hard labor.

U.S. Linking Sanctions and Security with the North Korean Human Rights Issues

There appear to be changes in how the United States responds to the North Korean human rights issue in relation to other issues due to the action of UN Commission of Inquiry. In the absence of measures to resolve the long-delayed North Korean nuclear issue, the U.S. is strengthening pressure on North Korea with regards to human rights violations. Previously, the U.S. listed North Korea’s denuclearization and suppression of military provocations as the priority and was comparably less interested in the human rights issues. However, the U.S is now strengthening the linkage strategy between North Korea’s nuclear problem and human rights as one of its strategies to deter North Korean nuclear development in order to induce North Korea to improve its human rights situation.

Three delegates from countries involved in the Six-Party Talks have officially begun to discuss the North Korean human rights issue. On May 27, 2015, the Chief delegates of Korea, the U.S., and Japan. Delegates are as follows: Hwang Joon-kook, Special Representative for Korean Peninsula Peace and Security Affairs; Sung Kim, U.S. Special Representative for North Korea Policy and Deputy Assistant Secretary for Korea and Japan; and Ihara Junichi, Director-General of Asian and Oceanian Affairs Bureau in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. They held a meeting about North Korea’s human rights problems and discussed multiple measures for maintaining the international community’s momentum. The delegates from South Korea, the U.S., and Japan did not explicitly announce the idea of adding North Korea’s human rights problems to the agenda of the six-party talks, but they emphasized the strengthening of pressure on North Korea through the human rights issue.

Furthermore, there is a trend toward strengthening of the U.S.-centered ROK-U.S.-Japan cooperation on the North Korean human rights issues. At the U.N. General Assembly in September 2014, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry led a high-level meeting on North Korea’s human rights situation with South Korean and Japanese foreign ministers. On July 8, 2015, the Heritage Foundation hosted the United States-Republic of Korea-Japan Ambassadors’ Dialogue where they discussed cooperation measures for resolving North Korea’s human rights problems.

Lately, there are increased movements in the U.S. to link North Korea’s human rights problems and sanctions. At the United States-Republic of Korea-Japan Ambassadors’ Dialogue mentioned above, Sung Kim stated that the evidence and information related to possible sanctions against the people in charge of activities which violate human rights within North Korea are under review.

On January 2, 2015, President Obama issued Executive Order 13687, which imposed additional sanctions with respect to North Korea. In this order, the United States defines the Sony Pictures hacking incident not as a simple hacking incident but as a violation of human rights which attempted to suppress the artists’ and individuals’ freedom of expression. In accordance with this executive order, the basis has been set for sanctions against individuals and organizations in North Korea that commit human rights violations. There are ongoing efforts in the U.S. Congress to link the North Korean human rights and sanctions. For example, the United States House of Representatives sponsored the ‘North Korea Sanctions Enforcement Act of 2015 (H.R. 757).’ On February 27, 2015 the House Foreign Affairs Committee held a Markup Session and the act is currently being revised. In this act, a broad definition of human rights violation such as what is happening in a political prison camp across North Korea is also regarded as a basis for sanctions.

Recommendations for South Korea

The targets of policy for improving North Korea’s human rights can be classified into two types: the North Korean authorities and the people. The character of North Korea’s human rights problem has been changing with the activities of the UN Commission of Inquiry. South Korea’s strategy in response should be established in view of changes in the nature of North Korea’s human rights problems. This paper suggests a series of recommendations for South Korea in dealing with the North under three distinguishable policy environments.

First, the international community’s strategy is essentially shifting from monitoring to full accountability. There is also a strengthening trend toward full-accountability-based pressure rather than engagement.

Second, international community’s pressure based on the full accountability seems to leave little room for North Korea to be flexible and forthcoming in its responses.

Third, as North Korea’s method of linking human rights, security, and national identity changes, there are increased trends toward linking human rights issues with nuclear development and sanctions, particularly in the U.S. Furthermore, ROK-U.S.-Japan cooperation regarding North Korea’s human rights problem is strengthened.

With the UN Commission of Inquiry in action, North Korean human rights issues display a strongly political aspect as human rights are more and more linked with other issues. There is a limit on how much progress can be made in North Korea human rights issues by focusing on the human rights issue alone. Therefore, South Korea’s strategy should be established having taken into account the political links between human rights on one hand, and security and sanctions on the other.

First, when considering the human rights issue, South Korea needs to consistently pursue a two-track strategy that contains both elements of pressure and engagement. As South Korea aims for the unification, it would be difficult to approach the North Korean human rights issues merely by applying pressure. In light of North Korea’s strong resistance against the full accountability-based strategy, South Korea needs to create more positive conditions for pursuing a North Korea policy that is more conducive to the unification of the Korean peninsula by pursuing a two-track strategy. Therefore, South Korea’s strategy should be established with a two-track approach of combining engagement against the external policy environment where accountability-based pressure is being strengthened.

However, South Korea’s establishment of the North Korean human rights strategy based on the two-track strategy of pressure and engagement faces two different policy challenges. First, pressure is growing in the international community for full accountability regarding North Korea’s human rights problems. Second, North Korea has used international pressure as a pretext to deny engagement with the international community. Because North Korea responds by linking pressure and engagement, it is not easy to achieve results by pushing ahead with a two-track approach of pressure and engagement.

In connection with the first policy obstacle, first of all, South Korea must effectively coordinate between its strategy oriented toward unification and the international cooperation focused on full accountability. In South Korea’s position, it cannot help but abide by the changes in the UN’s approach which features accountability-based pressure on North Korea. However, North Korea is responding with desperate measures to the UN’s approach from the perspective of “Supreme Dignity” argument. In this dilemma, South Korea needs to consistently maintain its traditional position that South Korea has always supported the UN’s approach. At the same time, even if human rights issues are not explicitly mentioned, South Korea needs to seek various methods to improve human rights condition in North Korea through the revitalization of inter-Korean relations. Until now, this kind of perception has rarely been seen in the inter-Korean relations. UN Commission of Inquiry recommends the United Nations to adopt the Rights-up Front strategy. South Korea should also induce an appropriate ministry to take the Rights-up Front strategy into consideration when setting up the inter-Korean cooperation strategy. In this regard, the human rights-based approach which is actively being discussed in the UN needs to be applied in correlation with South Korea’s situation. In particular, South Korea needs to establish its North Korea policy by taking into account the participation and empowerment of the North Koreans during the inter-Korean exchange and cooperation process.

The report by the Commission of Inquiry highlights the revitalization of the inter-Korean exchange and cooperation for improving the North Korean human rights situation. Therefore, South Korea needs to actively promote its position between aiming to improve the human rights situation through the inter-Korean exchange and supporting the international community.

In connection with the second policy environment, first of all, South Korea should try to create conditions for the activation of the UN human rights engagement mechanism so as to alleviate North Korea’s counter-strategy of linking pressure and engagement in the short run. More specifically, South Korea needs to increase diplomatic efforts to make conditions for the UN human rights mechanisms focused on engagement with regard to the UPR, technical cooperation with the OHCHR, and treaty-based bodies to expand their roles and responsibilities.

In particular, there is a need to actively utilize the UN human rights mechanism of engagement based on the countries’ obligations. Regarding treaty-based bodies to be relatively weak in political character, North Korea has tended to be cooperative with the treaty-based bodies until 2007. Therefore, South Korea needs to create conditions conducive for the activation of engaging North Korea to participate in the international community by emphasizing North Korea’s tendency to abide by and cooperate with treaty-based bodies.

North Korea has negatively responded to adopting a resolution for the sake of objectivity or selectivity targeting a specific country. However, UPR is free from criticism of double standards or selectivity in terms of targeting the entire United Nations Member States. Thus, there is a clear need to strengthen and expand the engagement strategy vis-à-vis North Korea by utilizing UPR. More specifically, South Korea can expand its engagement strategy vis-à-vis North Korea by focusing on the proposed resolutions on which North Korea expressed explicit acceptance.

Secondly, South Korea should weaken North Korea’s linkage strategy in which a response to the pressure-based strategy defines its response to the engagement-based strategy over the mid to long-term. In order to change North Korea’s action, which responds with both pressure and engagement, South Korea needs to use the North’s approach reversely. Because North Korea responds to accountability-based pressure by equating that as targeting the “Supreme Dignity,” relevant agencies in Pyongyang feel a lot of pressure. South Korea needs to establish a strategy for using it reversely. In this regard, it is important to induce North Korea to realize that the international actions for the accountability-based pressure will not be temporary.

South Korea should strengthen and maintain the visibility of North Korea’s human rights problem to make North Korea realize that the international efforts to hold human rights violators accountable will continue. Therefore, South Korea needs to play a leading role in maintaining the visibility of the North Korean human rights problem through communication, advocacy, and promotion in mid to long-term. For this role, South Korean government should play a leading role in establishing a complex, multifaceted cooperation network with international organizations, individual nations, internal and external NGOs. Taking into account North Korea’s response and the fact that the NGO’s role is strengthening in human rights field, South Korean government should reinforce public-private cooperation and provide support in building international solidarity with NGOs instead of directly getting involved.

If the pressure of full accountability continues in mid to long-term, it will become increasingly difficult for North Korea to reject all of United Nations human rights mechanisms. As part of its measures to alleviate pressure from international society in the mid to long term, it is possible that North Korea will adopt tactical acceptance, whereby North Korea accepts involvement of the United Nations’ human rights mechanisms. North Korea may also take positive actions, such as conditional permission for the UN personnel including the UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights Situation in the DPRK to visit North Korea, acceptance of technical cooperation with OHCHR, agreement to abide by the international human rights treaties, and partial implementation of the proposed recommendations by the UPR.

Lastly, South Korea needs to devise its own strategy to improve human rights after taking into account the political factors behind linking human rights issues with national security and sanctions. Under the current situation where the accountability-based pressure on the North Korean human rights problem continues, a simple human rights-based approach would be difficult to effectively deal with the linkage between human rights and national security. In order for South Korea to carry out engagement strategy against the backdrop of pressure strategy on the North Korean human rights issues, South Korea needs to take a strategic approach to weaken North Korea’s the linkage strategy between human rights and national security. Above all, in order to resolve the North Korean human rights problem, human rights strategy toward North Korea should be established to create a favorable condition in which linkage between human rights and national security can be weakened. North Korea is linking human rights with national security in response to the U.S. “hostile policy” toward North Korea. The U.S., in turn, is strengthening its human rights linkage in order to create a policy environment for the resolution of the North’s nuclear weapons program. North Korea and United States are both linking human rights with national security for the different purposes; however, the key chain in this linkage architecture is North Korea’s nuclear weapons program. In order to for South Korea’s strategy to produce tangible outcomes toward resolving the North Korean human rights problem through a two-track approach of engagement and pressure, human rights strategy toward North Korea must also take into account the North’s nuclear weapons problem. In this process, South Korea needs to find coevolutionary strategy to alleviate the North’s security concerns. ■

The East Asia Institute takes no institutional position on policy issues and has no affiliation with the Korean gov-ernment. All statements of fact and expressions of opinion contained in its publications are the sole responsibility of the author or authors.